Can Welsh Handball Bounce Back From the Brink of Extinction?

The ancient sport of Pêl-Law hangs on, barely, at the last court of its kind. A campaign to revive a related game may help bring it back.

“Will it be hard to find, do you reckon?” asks my friend Ben Coakley as he drives us through the rolling hills of southern Wales. The answer, we soon discover, is no. Half an hour north of Cardiff, we catch sight of our destination with ease: an imposing concrete structure that dominates a central location in the village of Nelson. More than 150 years old, it’s the last sports venue of its kind.

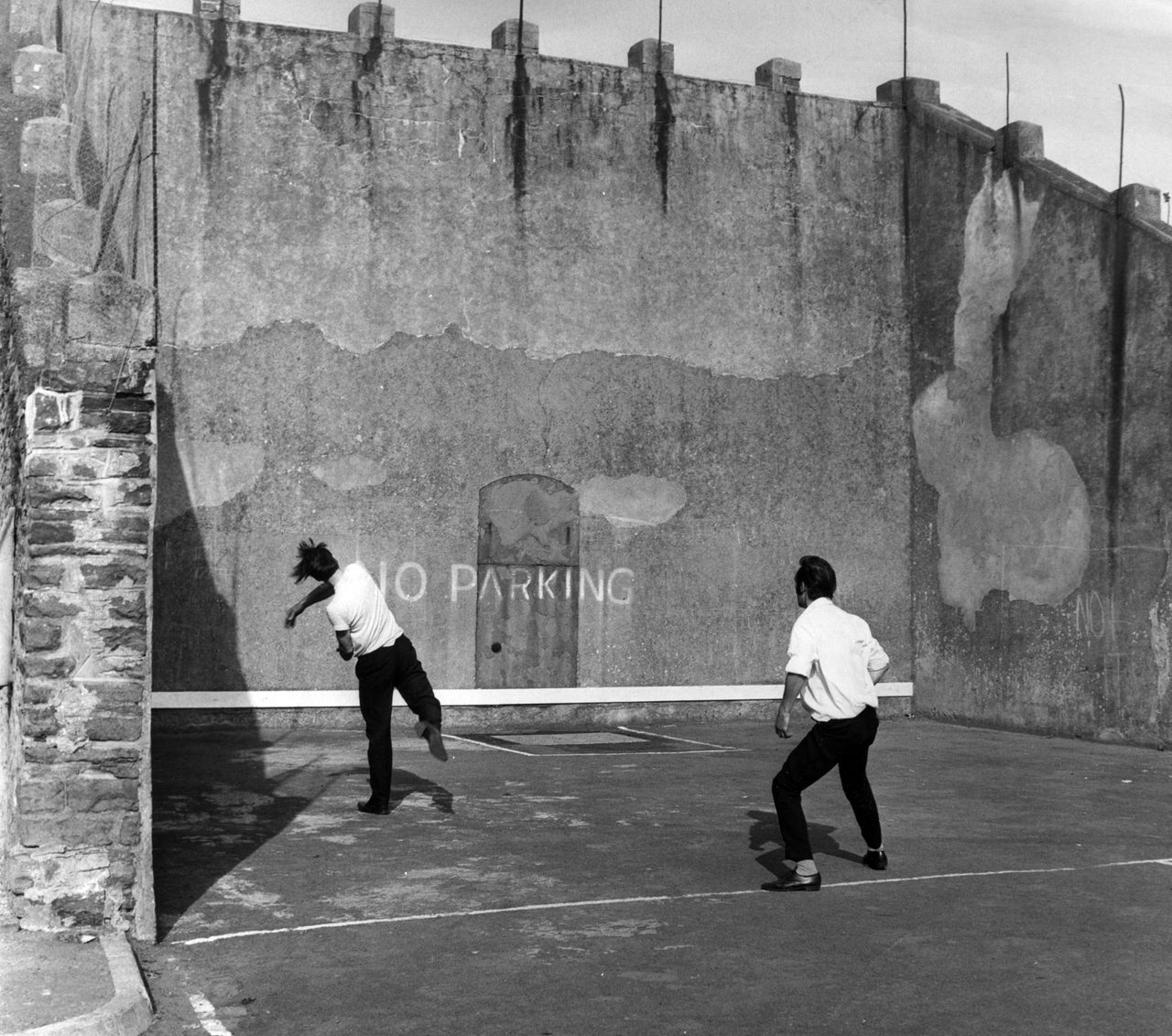

Flanked by The Royal Oak pub on one side and a small parking lot on the other, three hefty walls border a court more than 60 feet long and half as wide. The court surface and its towering center wall, some 30 feet tall, are marked with a few lines and boxes. The fourth side of the venue is open to a road busy with cars and trucks. This is the unassuming home of the ancient game of Pêl-Law, or Welsh handball. It’s the only functioning court in the country where the sport originated.

Ben and I are here to play—though, at first, we’re not sure how. “You’ll get it in no time. It’s just hitting a ball against a wall,” says Kevin Dicks, our mentor, as he joins us. Dicks, 63, uses a walking stick—owing to a couple of slipped discs, he tells us. He lives nearby, in Ystrad Mynach, and knows the Nelson court well. He’s the author of Handball: The Story of Wales’ First National Sport, and a former national champion of the game.

Dicks tosses Ben a blue rubber ball about the size of a lime and, after a quick summary of the rules, serves as referee for our first game. Thwacking a ball against a wall bare-handed feels immensely satisfying. Just as we’re getting the hang of it, Dicks sets aside his walking stick and takes us on, one against two. He beats us soundly.

The Nelson court is the last venue for a sport that may have descended from a version brought to the British Isles by the Romans some 2,000 years ago. The peak of Welsh handball’s popularity was in the 19th and early 20th centuries—the simple “ball and a wall” game was popular with miners—but it’s been on the decline for decades as flashier sports siphon off potential players. Now, Dicks and a handful of other enthusiasts hope a new version of the game can keep the long tradition alive.

Half an hour into play, we’re joined by Kerry Wilde, also 63. He lives a few minutes away and walked over with his obedient spaniel to watch our first foray. He was Welsh champion during the 1980s and ‘90s, and has been playing handball with Dicks since their school days.

There are several versions of handball bouncing around the globe today. The most widely played is team handball, which involves seven players per side, throwing balls towards goals. It bears no resemblance to the wall-based game Dicks and Wilde know. In wall-based handball, players take turns serving and receiving the ball, thwacking it back against the wall until it lands out of the court or bounces twice.

At the Nelson court, two versions of the game are played: wallball, where only one wall is used, and Pêl-Law, where players make use of three walls. The added variables in three-wall play make judging the ball’s path a challenge. “I always liked geometry,” says Wilde before firing a shot, pinball-like, off three walls.

Handball’s many incarnations evolved around the world thanks to the core simplicity. “Basically, every country hits balls against walls in different ways,” says Daniel Grant, founder of UK Wallball, which is working to popularize the one-wall version of the game. “In Spain there’s pelota, while throughout Europe we have Gaelic-style handball. Wales, with Welsh handball, is no exception.”

During Pêl-Law’s Industrial Age heyday, courts spanned the country, drawn out on the sides of collieries, schools, churchyards, houses, and, of course, pubs. The sport drew large crowds of spectators, including those who wagered the equivalent of thousands of pounds today.

In mid-19th century Nelson, the most widely used court was that of the Lord Nelson Inn. “The landlord of The Royal Oak wanted to steal trade away from the Lord Nelson Inn,” says Dicks. “He realized he could build a bigger court with more room for punters, so he did.”

Beginning in the 1860s, the Royal Oak court attracted players from all over Wales. It made Nelson a hub of Pêl-Law for the next five decades. However, following World War I, the sport fell into disarray. The number of courts dwindled as expanding towns ate up open spaces, and the popularity of team sports, prominent in army regiments, grew quickly in the civilian sphere as well. Handball was viewed as an antiquated pastime. The last Welsh championship, played by traditional rules that required wins in multiple venues, occurred in 1922.

In the village of Nelson, however, players continued to thwack and scramble around the three walls. The game hung on there, barely, even after the arrival of television, which expanded the popularity of team sports. Then, slowly, Pêl-Law started to make a modest comeback. A tournament in 1969 received a surprising 40 entries, and regular games returned to the court shortly afterward.

“In the ‘70s and ‘80s we had the handball world championships here, but it was just people from around Nelson,” says Wilde, who won the event several times. “We genuinely thought we were the only ones in the world playing.”

In 1987, the Welsh were invited to compete in a Gaelic handball tournament in Ireland. The game is similar to Pêl-Law but features a smaller, closed court. While the Irish won, the event thrust Welsh handball players onto the international scene. For the next two decades, several Welsh players competed globally, including in a one-wall version of handball—and the lines of play for that game were quickly added to the Nelson court.

“We understand why it was adopted as the international variant, it’s just easier to play,” says Wilde of the single wall game. “It reinvigorated the sport for us. We went all over the world competing: Chicago, Ireland, Winnipeg, Belgium.”

Nelson hosted the One-Wall European Championships in 1995, a moment of glory for the old ball court. It wasn’t to last. By 2006, the self-financed Welsh Handball Association, created in the 1980s, couldn’t afford to send players to tournaments. Local interest died down as well for both three-wall and one-wall play.

But, like a ball thwacked against a wall, handball seems to keep coming back. UK Wallball’s campaign has been gathering momentum, according to Grant. “It’s grown in the last ten years from a grassroots sport based in one London building to a national game which has thousands of kids playing,” he says. The organization’s first purpose-built facility opened in London in April.

Grant hopes wallball brings handball back to its roots as a community-focused pastime. “In Nelson and throughout Wales, handball was a genuinely working-class sport,” says Grant. “And today in New York and Europe, versions of the game bring communities together. We’d love to help that happen throughout the U.K.” He adds that UK Wallball players make a yearly “pilgrimage” to Nelson.

“It’s great what UK Wallball are doing,” says Wilde. “It’d be great to get some more regular games going again, to see some younger faces around here, whichever variant we’re playing.”

For now, the Nelson court doesn’t see regular use. Before he set down his walking stick to school us, Dicks hadn’t played for a few years. Wilde plays only occasionally, with his son Aled. And yet, as we head to our car, looking over our red and swollen hands, I overhear the two Pêl-Law old-timers in conversation. “You around this Sunday?” Dicks asks Wilde. “We may as well go for a hit again.” There’s life in the old game yet.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook