How Can a Basilica Stay Dry Amid Venice’s Rising Waters?

The race is on to save St. Mark’s—and its marble—from damaging, salty floodwaters.

As night fell over the northeastern Italian city of Venice on November 12, 2019, sirens wailed, signaling the arrival of a particularly high tide. At more than four feet above sea level, the city’s forecasting institute classed the tide as “exceptional,” but residents were prepared with electric pumps and steel barriers slotted into ground-floor doorways. As the night wore on, though, the tide rose far higher. Fierce winds and rain drove the water into the historic city, creating waves in St. Mark’s Square.

At St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice’s iconic Byzantine church, vicar Angelo Pagan rushed to move 17th-century pews and other precious objects clear of the water, but looked on helplessly as the tide reached more than six feet, the second-highest level ever recorded in the city.

The floods were cruel to the cathedral. Carlo Alberto Tesserin, who oversees the historic preservation of St. Mark’s, described the building as having “aged 20 years in a day.” And the damage wore on. Distressingly high tides continued for nearly three weeks, during which the basilica flooded two or sometimes three times a day. Ancient floor tiles were torn away, and in the church’s crypt, water rose high enough to nearly submerge the great stone tombs of previous patriarchs. Marble columns—particularly in the narthex, an entrance just before the main body of the basilica—were consumed by the sea, and glass from several windows was smashed by the force of water rushing in. All told, the floods left an estimated €300 million worth of damage. Now, as the city faces an increasingly flooded future, architects and curators have unveiled a provocative plan to keep St. Mark’s safe.

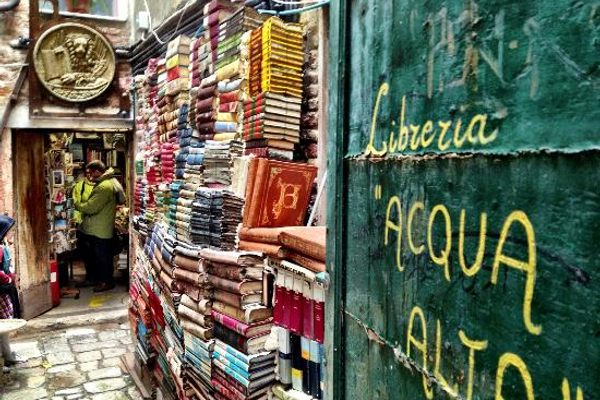

The 900-year-old cathedral is unfortunately flood-prone. St. Mark’s Square is the lowest-lying urban area in the city, and the narthex is its lowest point. A phenomenon known as acqua alta, which occurs when a high tide coincides with strong winds pushing water into the lagoon, regularly covers the piazza and the atrium of the basilica.

The basilica’s current flood defense system consists of automatically inflating barriers in the tunnels beneath the church that help redirect water out to sea. But these only protect the narthex, and can only withstand tides up to about 35 inches. That’s woefully insufficient, because local floods are poised to get even worse. City council records show that Venice is flooding more frequently, and at levels that are perilous for the basilica. In 2019, the city experienced 25 “exceptional” high tides, defined as anything over 110 centimeters (roughly 43 inches).

Rising sea level means that the tides are starting from a higher baseline, explains Jane da Mosto, an environmental scientist and founder of the nonprofit We Are Here Venice. According to a peer-reviewed study conducted by researchers at Germany’s Kiel University, Venice faces a sea-level rise of 55 inches and storm surges of 98 inches by 2100. Speaking at a conference in April, Mario Piana, chief architect of St. Mark’s Basilica, called these “truly unsustainable levels.”

Frequent contact with saltwater hurts the church’s marble columns, floors, and mosaics—and not only when it first seeps in. “It is a type of damage that is not immediately visible and that can occur even after a long time,” says Anna Maria Pentimalli, an architect and PhD candidate specializing in the restoration of architectural heritage who previously worked with a city body overseeing the protection of local heritage. Piana likened the cumulative effects to “radiation on the human body.”

The basilica contains scores of stones, and various materials respond differently to saltwater. The reddish porfido rosso antico marble, for example, which appears on the decorative floor, seems not to suffer any damage; other marbles, such as the dark green marmo verde antico or orangey rosso di Verona, may deteriorate quickly. Pentimalli explains that when the salt enters the stone, it causes exfoliation, cracks, and flaking. In the narthex, columns made from both marmo verde antico and rosso di Verona are showing serious degradation following the floods.

For months after the 2019 inundation, the basilica was washed with fresh water to counteract the salt deposits. Crews also used compresses of demineralized water to curb salt crystallization. Even so, salt crystals bloomed between the tiles on mosaics many feet in the air; the salt ate away at the mortar, causing tiles to fall. Work will be ongoing. Speaking to local media a couple of months after the flood, Tesserin said, “Almost 60 percent [of the floor] will have to be replaced and we will need years to complete the works.”

The basilica will need a longer-term solution, too, and the one in place for the rest of Venice isn’t going to cut it. That system—a network of flood barriers, dubbed MOSE—came into operation last July, after years of delays and corruption scandals. Positioned at the three entrances to the Venetian lagoon, these gates can be raised when a high tide is forecast, helping to prevent seawater from entering and flooding the city.

However, they are currently only activated when a tide is forecast to reach at least 51 inches. In the future, that threshold may be lowered to deal with floods reaching 43 inches—but that won’t be much help for the basilica, where the narthex floods at around 26 inches. As da Mosto explains, “To protect the Basilica, [MOSE] would need to be closed at lower water levels,” which would mean using it more often. That would be energy-intensive, and also impact port and fishing activities, da Mosto adds, which rely on moving between the lagoon and the sea.

With the MOSE system unable to fully protect the basilica, the building’s custodians have proposed independent flood defenses. Headed by engineer Daniele Rinaldo and architect Mario Piana, the €3.5 million interventions aim to protect St. Mark’s against up to 43 inches of water, at which point the MOSE barriers would take over.

The first intervention is a system of manually operated valves inserted in the drainage tunnels beneath the basilica to intercept the water before it gets too close. A similar design already exists in the narthex; this one would snake around the perimeter of the building.

Because the basilica is also inundated with water from the piazza outside, a physical barrier to prevent the flow of water from square to church also has appeal. A controversial proposal by Rinaldo and Piana entails installing a temporary, four-foot glass barrier in front of the church. The wall would prevent corrosive seawater from entering and eating away at the marble floors and mosaics, but the potential visual impact has sparked some objections. “A physical barrier risks losing the natural architectural continuity seen now,” says Pentimalli.

The concepts have already been approved by the local heritage body Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio, as well as the region’s Ministry of Public Works, but progress is delayed because of concerns over the cost. The projects are a little outlandish, but proponents argue they might be what it takes to preserve one of the finest examples of Italo-Byzantine architecture. “The Basilica must be protected, and one cannot think of letting it continue to suffer damage like that from the continuous cycles of tides of recent years,” Pentimalli says. “To extreme evils, extreme remedies.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook