Around the World in 125 Melons

It took nine years to grow and photograph all the melons in this book.

Sometimes seasons change in the blink of an eye. One moment, stores have stocked winter tangerines; the next, it’s spring strawberries or the cherries, peaches, and melons of summer. Like many of us, melon fanatic Amy Goldman probably wishes that summer was 10 times as long. After all, it took nine New York summers to grow and photograph enough comely cucurbits for her upcoming book, The Melon.

But that’s all right. For Goldman, “Melons are a life-long love and calling.” In fact, it’s been nearly 20 summers since Goldman published her last book on the subject: 2002’s Melons for the Passionate Grower. According to Goldman, it was only after a career as a psychologist (as well as multiple victory laps at vegetable-growing competitions) that she turned to writing comprehensively about melons and watermelons, both of which belong to the Cucurbitaceae family. The vining berries stemmed from Africa, and twined outwards. “Various lineages found their way time and again to different continents by transoceanic long-distance dispersal,” Goldman writes, before adding, “Picture gourds afloat!” The book floats along the same path, featuring 85 melons and 40 watermelons from around the world, along with advice on growing, picking, and loving them.

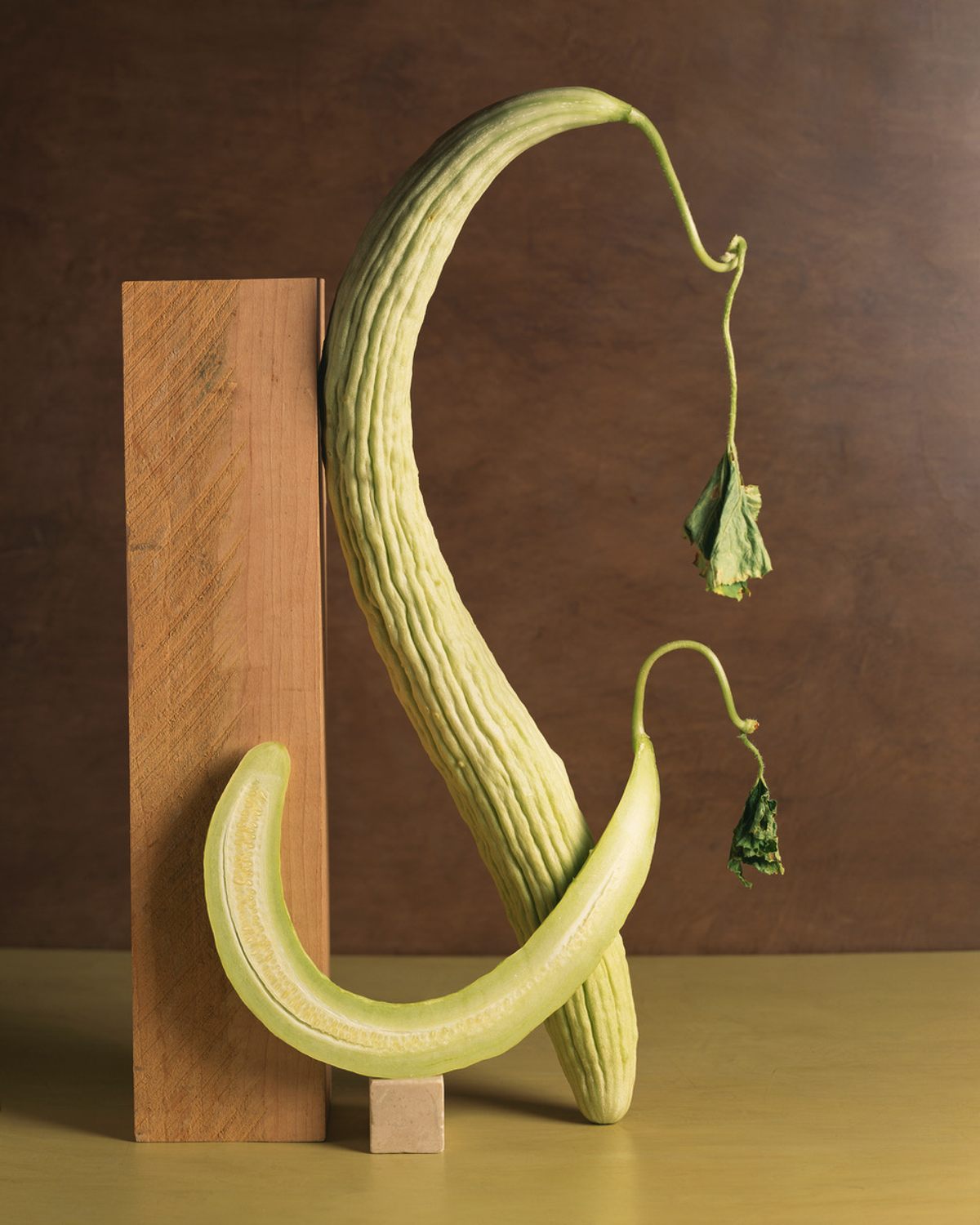

In writing that verges on romantic, Goldman describes “her first melon love,” the wrinkly, yellow-green Santa Claus casaba, while beautiful photographs by Victor Schrager showcase the glorious spectrum of melon shapes. The Jenny Lind, named for the 19th-century opera singer, looks vaguely like a clove of garlic. The elongated and yellow Banana melon is aptly named, although with a very different, “heaven-sent” flavor. The Mango melon, whose scent evokes “flowers and cinnamon,” is more rotund.

Some melons are even more wondrous, such as the Queen Anne’s pocket melon. Though its origins lie in Persia, legend has it that English women once carried the powerfully fragrant, minuscule melons as a kind of proto-deodorant. Despite their perfume, though, the pocket melon is seedy and tasteless. But this isn’t a problem with the Killy Edible-Seeded. Known in China as the Wanli, its big seeds are the tastiest part, after they’ve been cracked open to give up their nutty interiors. Even more marvelous are Indian snap melons, whose delicate skins burst open when they reach maturity.

Melon anecdotes abound in the book. When describing the monstrous Bidwell Casaba, a winter melon bred by the American Civil-War era general John Bidwell, Goldman affectionately introduces a fellow melon lover. Bidwell’s houseguests were less indulgent. “My God, casabas for breakfast, casabas for lunch, casabas for dinner!” raged fellow general William Tecumseh Sherman.

All this joy over melons, though, is haunted by the specter of loss. While the world of heirloom melons is vast, modern agriculture tends to focus on longer-lasting, less finicky, and less spectacular varieties. In several cases, a single family has become sole guardian of a particular variety, from the Rescans in Cesson-Sévigné, France, and their Petit Gris de Rennes melon, to the Cranes of Santa Rosa, California, who sell delicate Crane melons from the family barn in early to mid-fall.

Twenty years ago, Goldman was sent a box of melon seeds from the organization Seed Savers Exchange. Some of the melon seeds were nearly the last of their kind. As a result, Goldman writes, she had nightmares about the precious plants being stolen from her garden.

But the rest of the time, Goldman’s melon growing seems more like a dream—one populated by the endless melon and watermelon varieties bred by our ancestors. “We are the heir to a vast fortune,” Goldman writes, one that comes in all shapes, sizes, and sweetnesses.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook