The Surprising Resilience of the Hog Island Fig

Virginia’s Eastern Shore has rallied around a sweet, centuries-old local delicacy.

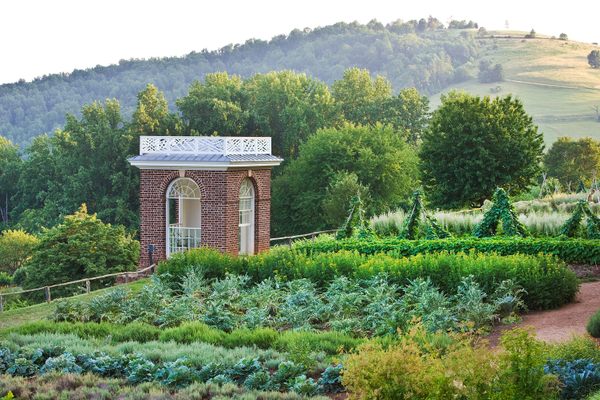

On an abandoned island off the coast of Virginia, fig trees sprout up on the grounds of a demolished lighthouse. Although human residents left the island in the 1930s, leaving scant ruins in their wake, the fig trees serve as a living remnant of a bygone era.

Situated a few minutes away from Cape Charles, Hog Island has a long history of being inhospitable to humans. Before colonial settlement, Eastern Shore tribes used the land only during fishing and hunting season. In fact, its original name, Machipongo, means “fine dust and flies” in Algonquin.

In 1672, British colonists came to live on the island, many of whom planted fig clippings brought from Europe. But these settlers soon disappeared—an enduring mystery, as there are no records indicating why—and it wasn’t until after the Revolutionary War that the island hosted another community. These islanders—who eventually named the area after a landowner named Captain Hogg—built homes, established families, and developed the island into a charming, secluded escape for visitors seeking respite from nearby congested cities and towns.

This dreamy era wasn’t to last, however. In the 1930s, severe hurricanes began battering the island, forcing residents to relocate to nearby mainland towns such as Willis Wharf and Oyster. One hurricane, known as The August Storm, killed multiple people in Virginia in 1933. It was around this time that most islanders decided it was too dangerous to stay and moved their homes and possessions via barges to the nearby mainland. Along with these treasured pieces of their lives, many residents also took clippings of the local fig trees and planted them around their homes on the mainland.

A quick primer on the Hog Island fig: The name actually encompasses two recognized varieties. One, known as the Higby fig, is prized for its sweet, nectary tang. The Higby is related to the silver leaf fig, which was first documented in Cape Charles in the 1940s, although it could possibly have been around since the 1600s, making it potentially one of the oldest strands left in the South.

The second variety of the Hog Island fig is tinier (it measures about one inch all around), but has the more outsized reputation. Commonly referred to as the Grover Cleveland fig, it earned its fame, and its name, with an appearance at an 1892 feast thrown for President Cleveland. Fresh off his victory for a second term, Cleveland decided to celebrate with a hunting trip to Hog Island. After treating Cleveland to a hearty meal at the luxurious Broadwater Club, islanders presented the preserved local figs as a dessert. It’s rumored that Cleveland loved the figs’ rich, floral-honey tones and that a small fig tree was later sent to the White House as a gift.

Both figs are beloved for their flavor, a byproduct of their terroir. According to Dr. Bernard Herman, author of A South You Never Ate: Savoring Flavors and Stories From the Eastern Shore of Virginia, the coastal environment helps the figs flourish with plentiful salt. This is why the clippings brought to the Eastern Shore by Hog Island residents nearly a century ago have continued to produce delicious figs in their new home. Thanks to those clippings, most of the older Eastern Shore homes now feature at least one fig tree on the property.

Today, Eastern Shore residents still take great pride in the Hog Island fig. After the figs make their debut each July, residents will often pluck the ripened crops off of the trees to eat immediately, or collect them to make preserves and jam. Local home cooks are also prone to mixing them into an array of baked goods, including a fig ribbon cake recipe dating back to the 1880s. But not all the recipes are historic; local chefs also experiment with the figs and concoct their own contemporary takes, such as a sweet and spicy salsa featuring fig chunks.

To help maintain these longstanding culinary traditions surrounding the Hog Island fig, the area’s Barrier Islands Center hosts fig-preserve demonstrations and the local historical society holds cooking classes. At one of these sessions, a local chef designed a dish that combined farm-raised mutton with rosemary, garlic, and figs.

These culinary celebrations are part of a larger, local effort to save the Hog Island fig. Although the trees have withstood centuries of storms and abandonment, they are now threatened by the effects of climate change and, specifically on Hog Island, erosion. The trees’ future now depends on residents actively cultivating them. As part of his efforts to promote and preserve it, Herman successfully petitioned for adding the Hog Island fig to the Ark of Taste, a registry of foods with distinct local heritage that are at risk of going extinct within two generations.

Herman also employs a more direct approach of educating locals about the fig and inspiring them to cultivate their own. Matt Ertle, owner of Island View Farm & Seaside Lamb in Cape Charles, recalls when Herman first introduced it to him. “My family moved to the Eastern Shore about 10 years ago and I didn’t know much about it,” he says. When Ertle told as much to Herman, “he brought a Hog Island fig bush with him and explained its history, which I thought was pretty cool.”

Today, Ertle grows fig trees on his sheep farm and, at one point, sold the figs at the local farmers’ market. Today, though, he mostly shares the delicious treats and some clippings with friends and neighbors. In fact, this is often how most of the figs in the region have spread, with neighbors offering cuttings to one another in a friendly exchange that spans generations.

While the trees are at risk of eventually disappearing, there is hope: They are, for now, surprisingly easy to grow in the area. “I don’t have much of a green thumb, so I love the Hog Island fig in particular because I don’t have to really do anything to it,” says Ertle. “It’s one of the few fruits that grow well here without much effort.”

Herman says the fig is worth preserving for reasons that go beyond its culinary value. The trees, scattered throughout these Virginia seaside communities, serve as living museums providing a glimpse into the history of a once-thriving island. “These figs are very much about preservation of a place in history.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook