Twirl Paper Umbrellas at the Vintage Tiki Bars That Taught Americans to Relax

The tiki bar tour of your chill vibey dreams.

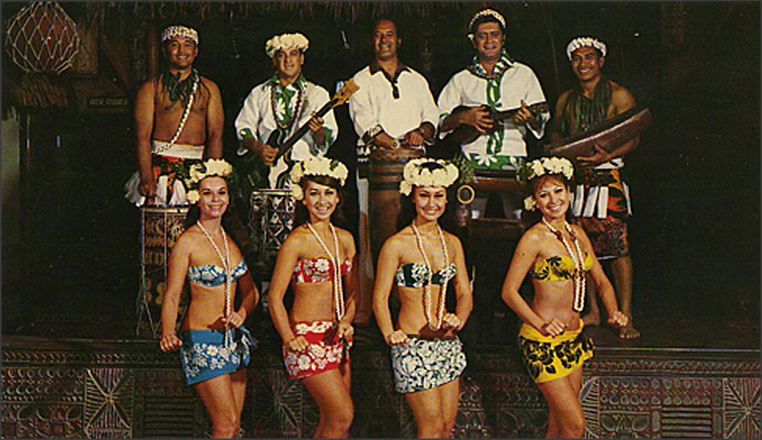

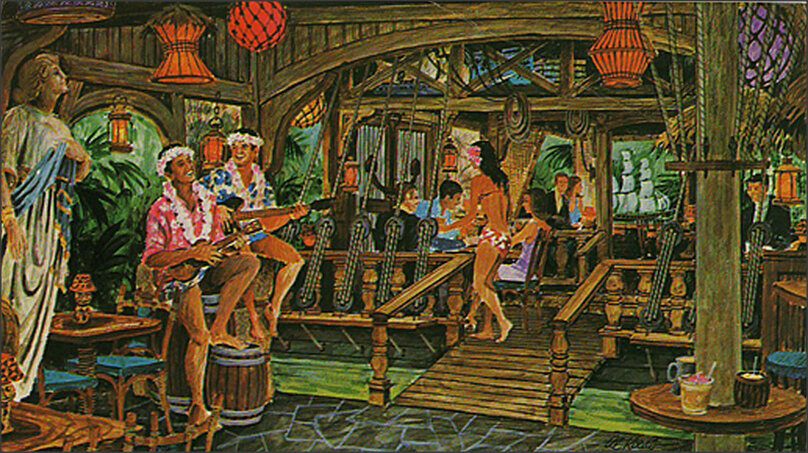

Dancers and musicians at the Mai-Kai, circa 1950s. (Photo: 1950sUnlimited/CC BY 2.0.)

As Hollywood boomed in the early 1930s, moviegoers wanted to see more of the world, and the film industry had the means to show it to them. Films set in exotic locations grew popular for this reason, with South Seas-inspired stories becoming a particular draw.

Decades before South Pacific hit Broadway stages, films of the era featured white, male adventurers and native maidens grappling with magical island enchantment, shipwrecks, pirates, romance, and the like. They were a hit, and Polynesia became the de facto image of paradise in America’s collective imagination.

Enter the tiki bar. At these tropical establishments, patrons could soak up the atmosphere and excitement of the South Pacific without even leaving their suburb. Of course, much of the ambience they were soaking up was not an accurate representation of life on a Pacific island.

Postcard advertising the Menehune Banquet Room at the Waldorf in Vancouver, c. 1950s (Photo: Rob/Flickr)

The palm trees were plastic, the food was Americanized Chinese, the decor was a messy blend of imitation Polynesian, Caribbean, and African indigenous art, and the hula dancers were usually Midwestern brunettes with spray tans. Midcentury Tiki culture fetishized island life, to be sure, and it largely faded out when its faux primitivism began to seem tacky.

But American tiki isn’t quite done yet. A kitsch renaissance in the 1990s made way for a number of new tiki bars you can visit today, and a handful of the original vintage locales still exist.

It all started with Don the Beachcomber.

Don the Beachcomber

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIFORNIA

Ernest Beaumont Gantt, a.k.a. Donn Beach, at the Beachcomber Cafe. (Photo: Hawaiian Beachcomber)

Ernest Beaumont Gantt made his way through the Depression as a bootlegger, but when prohibition ended he was out of a job. He worked a number of odd jobs, but having traveled in the Caribbean and Pacific, he found himself successful as a technical advisor on the numerous South Seas films Hollywood was churning out.

In 1934 he opened a bar in Los Angeles where he made rum drinks (it was the cheapest liquor he could get) and decorated it with Polynesian flair he had collected, along with buoys and nets he scrounged up from the waterfront. He named it the Beachcomber Café, and he put his all into making patrons feel as though they were in a little grass shack somewhere far off in the Pacific.

Gantt cast himself as the master of ceremonies and legally changed his name to Donn Beach. Celebrities and civilians alike flocked to the Beachcomber, and Donn knew how to keep them there: knowing customers were more likely to stay for another drink if the weather was inclement, he created his own tropical rainstorm via garden hose on the roof. Soft ukulele and “exotica” music was ever-present, both played live and piped in. Eventually there would be a myna bird trained to say, “Give me a beer, stupid.”

Bob Hope learns to hula at Don the Beachcomber in Waikiki. (Photo: Hawaiian Beachcomber)

Despite the fact that he himself was drafted, World War II turned out to be the best thing that could have happened to Donn Beach and the tiki craze. First, thousands of American youth were shipped out to the Pacific, where many of them were seeing palm trees and beaches for the very first time. Military men brought back coconut shells and grass skirts to their new suburban homes. News of this paradise came back from overseas, and the idea of a tropical vacation began to grow in the American pop culture consciousness.

Second, while Donn was overseas, his wife Sunny managed Don the Beachcomber (the bar, not the man). She turned out to be twice as savvy as he, and expanded the establishment into a chain, and a popular one at that.

Various copycats ensued, including the highly successful Trader Vic’s.

Trader Vic’s

ATLANTA, GEORGIA

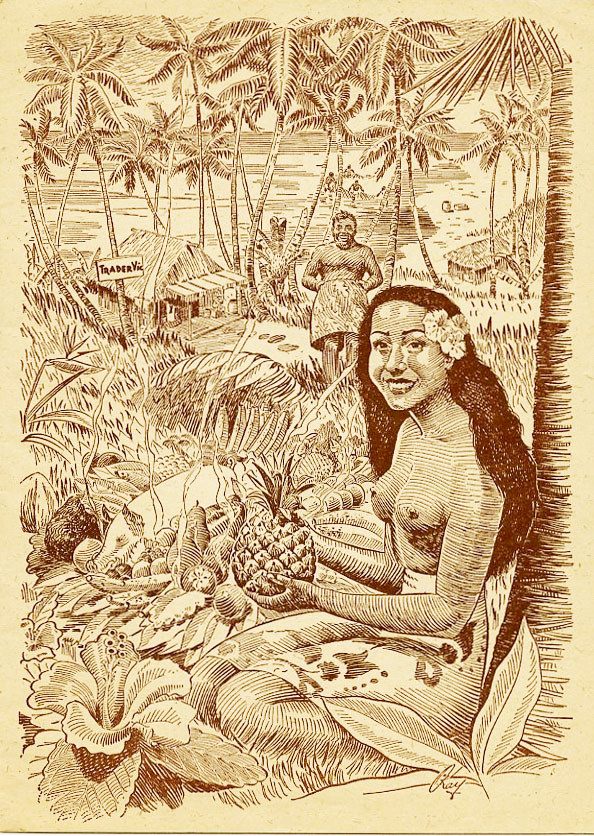

Illustration from the cover of a Trader Vic’s menu. (Photo: California Historical Society)

Spotting the burgeoning popularity of all things tropical, Victor Bergeron opened a bar across the street from his parents’ grocery store in Oakland, California in 1934, around the same time Donn opened the Beachcomber.

If “Trader Vic’s” sounds familiar, it’s because the grocery chain Trader Joe’s borrowed their name from Vic’s, along with its trading post vibe. They’ve largely since moved their brand away from its tiki-inspired origins, though their employees do still wear Hawaiian shirts.

To be fair, the jury is out on who stole from whom. Both Donn Beach and Victor Bergeron (Trader Vic) laid claim to the invention of the Mai Tai cocktail (which translates to “good” in Tahitian), and both dressed their restaurants in the style that would become iconic to tiki bars.

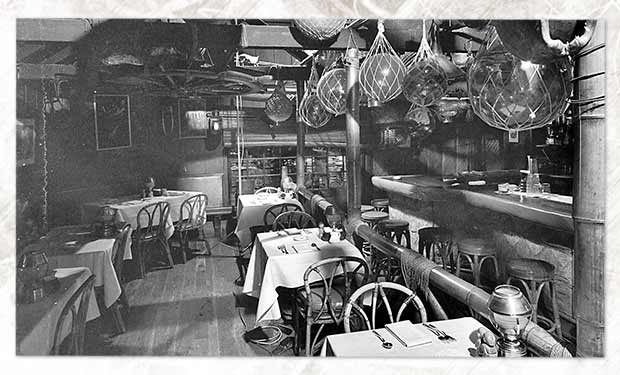

One of the first Trader Vic’s restaurants. (Photo: Trader Vic’s Atlanta)

They remained in friendly competition throughout their entire careers, but while Donn went for celebrity and spectacle, Vic sought quantity in his business. Part of what attracted folks to the tiki craze was the feeling of escapism. If you couldn’t get to the Pacific, it was no matter — a temporary vacation was available to you at Trader Vic’s. To capitalize on the desire for cheap, easy leisure, Vic opened dozens of his restaurants in domestic and international hotels.

While Donn and Vic expanded their chains around the world, clubs like the Tonga Room in San Francisco focused on exclusivity.

Tonga Room

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

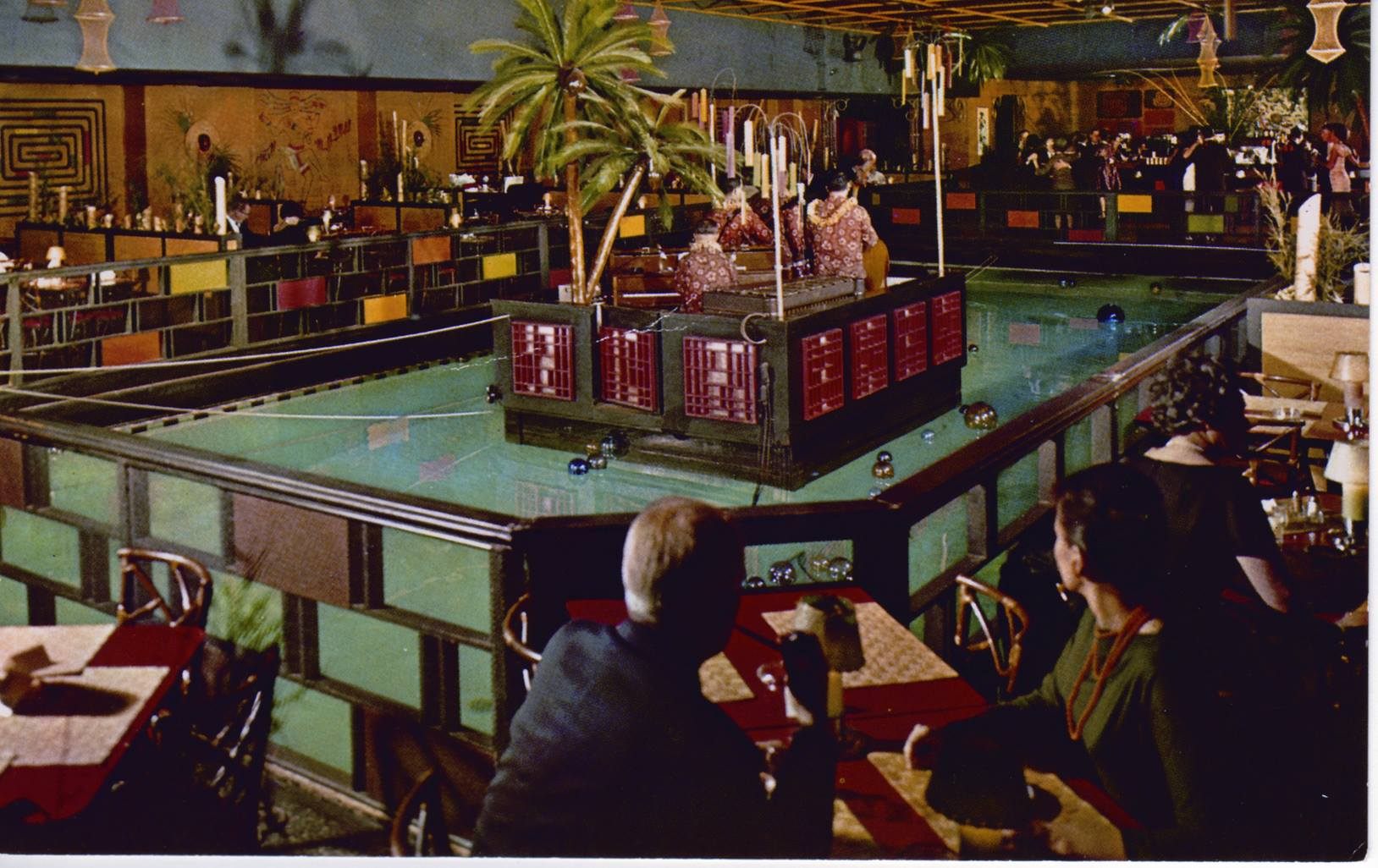

The band plays atop the Tonga Room’s central pool. (Photo: The Tonga Room and Hurricane Bar)

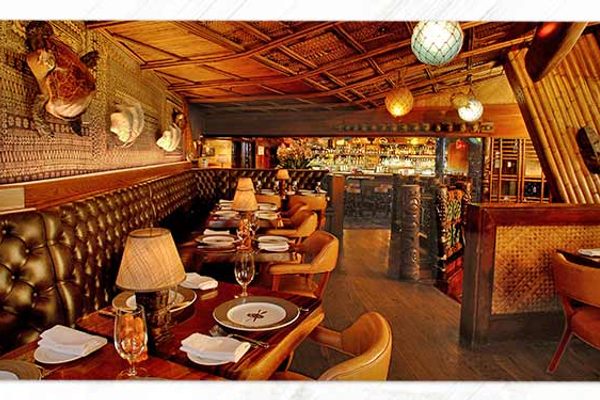

The Tonga Room was one of the first “high style” tiki bars. Rather than a dive bar in a wooden shack, the dining club was elegant and glamorous. It represented a new style coming into vogue.

As tiki fever caught on, its aesthetic was enveloped into high culture. Rather than being considered low class, “primitive” carvings and bamboo rattan furniture were modish and chic. Architects built A-frame houses in imitation of indigenous Pacific longhouses. Women began wearing hibiscus-printed barkcloth dresses. Exotica musicians like Les Baxter and Martin Denny fused American jazz with bongos, marimbas, vibraphones, and even bird calls in what would become quintessential lounge music.

And of course, it would be a mistake to forget Elvis Presley’s association with Hawaii, which went on to inspire the decor of his favorite room in Graceland.

The Jungle Room at Graceland

MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE

Movie poster for Girls! Girls! Girls!, one of three films starring Elvis in Hawaii. (Photo: Paramount Pictures)

Tiki culture, Polynesian pop, the look of the South Seas—whatever you want to call it, it was fully a part of American pop culture by the 1950s. This was mirrored in the media, and who better to capitalize on America’s tropical fascination than the King himself? Elvis signed a contract to film three musical movies in Hawaii, and out of these came some of his greatest hits, including “Love Me Tender” (from Blue Hawaii) and “Return to Sender” (from Girls! Girls! Girls!). He loved Hawaii, and returned there often, most notably for “Aloha from Hawaii Via Satellite”, one of the first live televised concerts, which saw the debut of his famous white jumpsuit.

Elvis’ connection to Hawaii was so intense that he wanted to recreate it at home, which he did in his Jungle Room in the Graceland Mansion. Complete with a bar and waterfall, it was the ultimate at-home tiki bar, a mark of fully realized American leisure.

In all three of the Hawaiian films Elvis played a version of the same character—a young man who, instead of performing his duties as a pilot/fisherman/heir to a pineapple plantation, only wants to surf and flirt. This symbolized a new epoch in youth culture, and the carefree, fun-loving ethos of tiki culture suited it perfectly. All around the United States, tiki bars, restaurants, and even amusement parks cropped up so that the new, young middle class could let loose and “go native”, as so many of them put it.

Mai-Kai

FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA

Dancers and musicians at the Mai-Kai. (Photo: 1950sUnlimited / CC BY 2.0)

There were places like the Mai-Kai in Fort Lauderdale that used the Floridian landscape to recreate a Polynesian fantasy, complete with dancers and musicians. More than just a place to get a drink and eat semi-exotic food, the Mai-Kai was intended to be an experience. It featured eight dining rooms, each representing a distinct group of Polynesian islands, a lush tropical garden, and a floor show complete with fire eaters.

On the other coast of Florida, Indian Shores was home to Tiki Gardens, a Polynesian theme park. But of course, the good people of middle America wanted a tropical getaway in their neighborhood too, climate be damned.

The magnificent Kahiki Supper Club (Photo: Swanky / Critiki)

The Kahiki Supper Club in Columbus, Ohio, became a destination for those near and far. It came closer to an amusement park than a restaurant, featuring massive, flaming tiki heads at its towering entrance, an indoor lagoon, and the pièce de résistance: the Mystery Girl.

Whenever a Mystery Drink—a punchbowl of rum cocktail with a smoking volcano in the middle—was ordered, a beautiful, unnamed dancer would deliver it to the customer with a fresh orchid lei, a kiss on the cheek, and a dramatic bow to a tiki head, and disappear with the bang of a gong. This schtick may have been stolen from the Mai-Kai in Florida; it can be hard to determine the source of the reproductions of tiki, which were all imitations of Polynesian affects anyhow.

A Mystery Girl at the Kahiki Supper Club. (Photo: Ronald Ortman / Critiki)

Like any fad though, tiki eventually grew outdated. Air travel was easier than before, and with more access to the actual Pacific, tiki recreations began to seem gaudy and gauche. After the horrors of the Vietnam War were broadcast across the States, glamorizing the lives of indigenous peoples lost some of its escapist gleam.

Tiki establishments across the country snuffed out their torches and shuttered their doors. But a handful of original vintage tiki bars still exist. Most franchises of Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic’s did not survive, but Montanta’s Sip ‘n Dip Lounge did. Los Angeles’ Tiki Ti has stood the test of time as well, perhaps because its founder was the original bartender at Clark Gable’s on-set bar during Mutiny on the Bounty, Christian’s Hut.

Sip ‘n Dip Lounge

GREAT FALLS, MONTANA

The Sip ‘n Dip Lounge. (Photo: O’Haire Motor Inn’s Sip ‘n Dip Lounge)

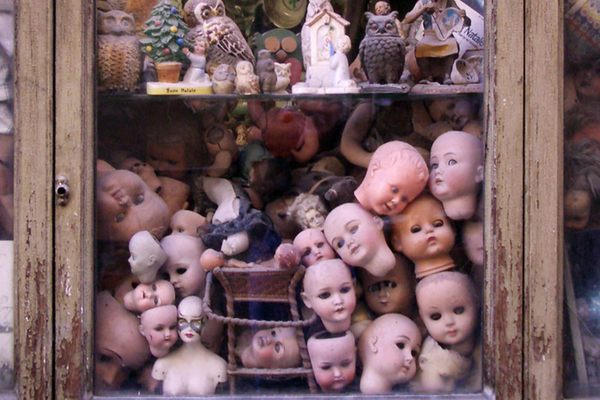

A kitsch renaissance in the 1990s made way for a number of new tiki bars, and ever since then their numbers have steadily increased. New York has few, including Otto’s Shrunken Head. Las Vegas has Frankie’s Tiki Room; Vancouver hosts the Shameful Tiki Room. The most famous tiki room is Walt Disney’s “enchanted” one, though it’s also probably the only one that doesn’t serve alcohol.

Today, few are under the illusion that a visit to a tiki bar is representative of any authentic Pacific culture. In fact, most tiki enthusiasts are not even referencing the actual Pacific when they don Hawaiian shirts and host backyard luaus.

Rather, they are engaging in a nostalgic fantasy for the novelty of a bygone era. Tiki culture is a romanticized copy of a copy of Polynesia, a plastic paradise native to nowhere. Next time you find yourself in a tiki bar, take a second to bask in the midcentury kitsch that gave us Mai Tais, the limbo, and dashboard hula girls.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook