The Radical Roots of Britain’s Last Temperance Bar

It’s now a monument to a forgotten campaign against alcohol.

A whiff of medicinal sarsaparilla. The earthy aroma of dandelion and burdock. The sweet tang of blood tonic. “It had such a stunning smell about it,” says Ashleigh Morley-Doidge, reminiscing about her childhood trips to Mr Fitzpatrick’s in her hometown of Rawtenstall, England. Morley-Doidge—who now owns Mr Fitzpatrick’s, Britain’s only surviving 19th-century temperance bar—recalls it as a dimly lit but enchanting place, with shelves crammed full of herbs in towering glass jars.

Not much has changed at the bar over its 122 years of existence. The menu still revolves around 16 traditional botanical cordials, concocted with herbs, fruit, and spices. Patrons can either take a bottle home or quaff their drink in-house, surrounded by cabinets still cluttered with herbs and ceramic serving pots. Some careful restoration by Morley-Doidge means there’s more space and light now, and more drink flavors, like rhubarb and rosehip, have joined the others behind the bar. Morley-Doidge has also reluctantly banished that memorable, heady smell. A necessary evil, when she realized it was emanating from a carpet soaked with generations of spilt sarsaparilla.

It would be easy to sketch Mr Fitzpatrick’s as a quaint historical anomaly. It’s a bar that has only ever served nonalcoholic drinks in a small mill town in the north of England, on an otherwise beer-glugging island. But when Mr Fitzpatrick’s of Rawtenstall opened in 1899, a bar with no booze on the menu wouldn’t have seemed extraordinary at all.

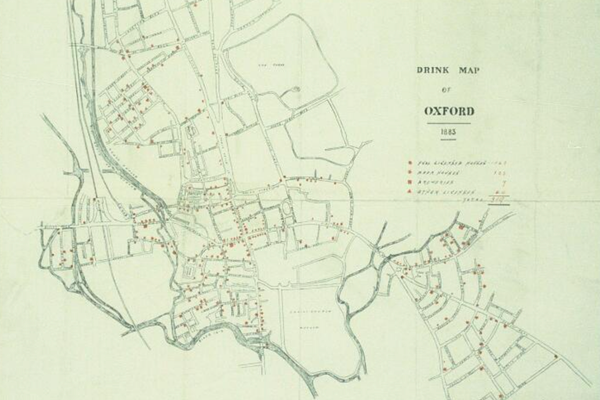

Established by a family of herbalists from Dublin, Mr Fitzpatrick’s Rawtenstall location was just one of a chain of 40 temperance bars in the industrial towns of northwest England. The Fitzpatricks were late to the game by several decades. By the time Mr Fitzpatrick’s opened its doors, most British cities had a “temperance hall,” and alcohol-free hotels, pubs, and billiard rooms could be found throughout the country.

“There was practically an alternative world,” says Dr. Annemarie McAllister, temperance historian at the University of Central Lancashire. “Many of our well-known theaters either started out as, or for a while were temperance music halls.”

Records suggest that by 1900, more than 6 million people had taken “the pledge,” meaning nearly a tenth of the adult population had chosen to turn their backs on booze. But despite the numbers, McAllister says that the history of the British temperance movement has largely been forgotten, or, when it is remembered, is grossly misrepresented. Activists didn’t oppose alcohol out of conservatism, and their efforts weren’t spearheaded by the church. “Teetotalism was a movement of working people taking action to change their own lives,” McAllister says.

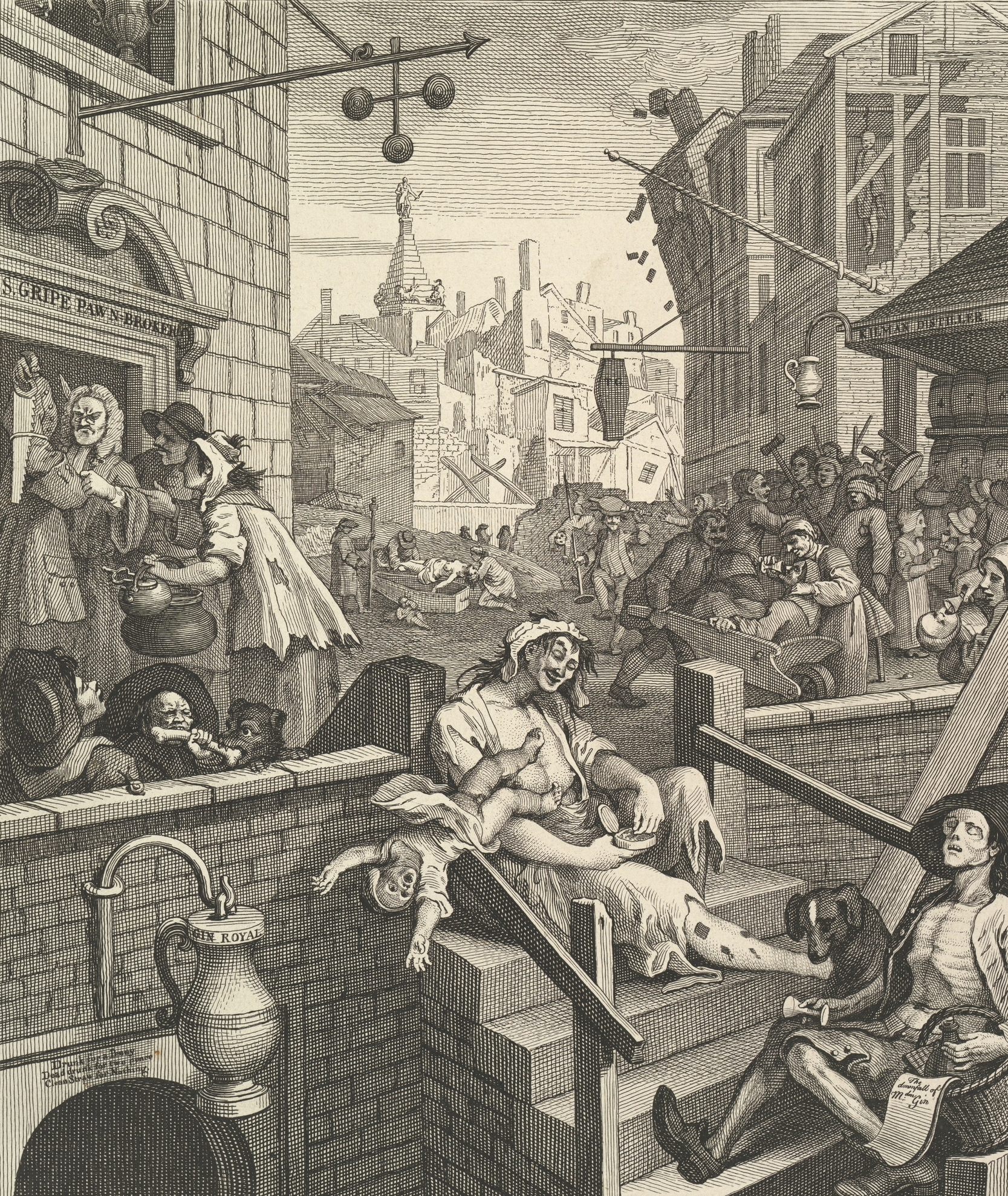

The 18th century had seen a gin-drinking craze sweep the country. By 1730, it was estimated that the average Londoner was consuming more than 10 gallons of gin every year. As famously depicted by William Hogarth in his 1751 print Gin Lane, excessive drinking led to nationwide social and health problems. The bleak image blamed the Dutch-produced spirit for widespread intoxication, child neglect, poverty, violence, and death.

In response to the crisis, the government promoted less-potent English beer as a healthy alternative to dangerous continental spirits. In 1830, it passed the Beer Act, allowing any homeowner to open a “beerhouse.” The results were predictable. There was a huge uptick in public drunkenness, particularly in the increasingly industrialized northern cities. Given the bleak lives of the factory workers, it was little wonder that many sought out oblivion. Beerhouses also provided warmth and companionship for workers. However, McAllister’s book Demon Drink? Temperance and the Working Class quotes a local newspaper on a less than comforting scene. “Men, women, and children in the evening were in the streets in a disgusting state of intoxication,” the article recounted. “Six, stripped of all but their trousers, fought till blood streamed from their faces.”

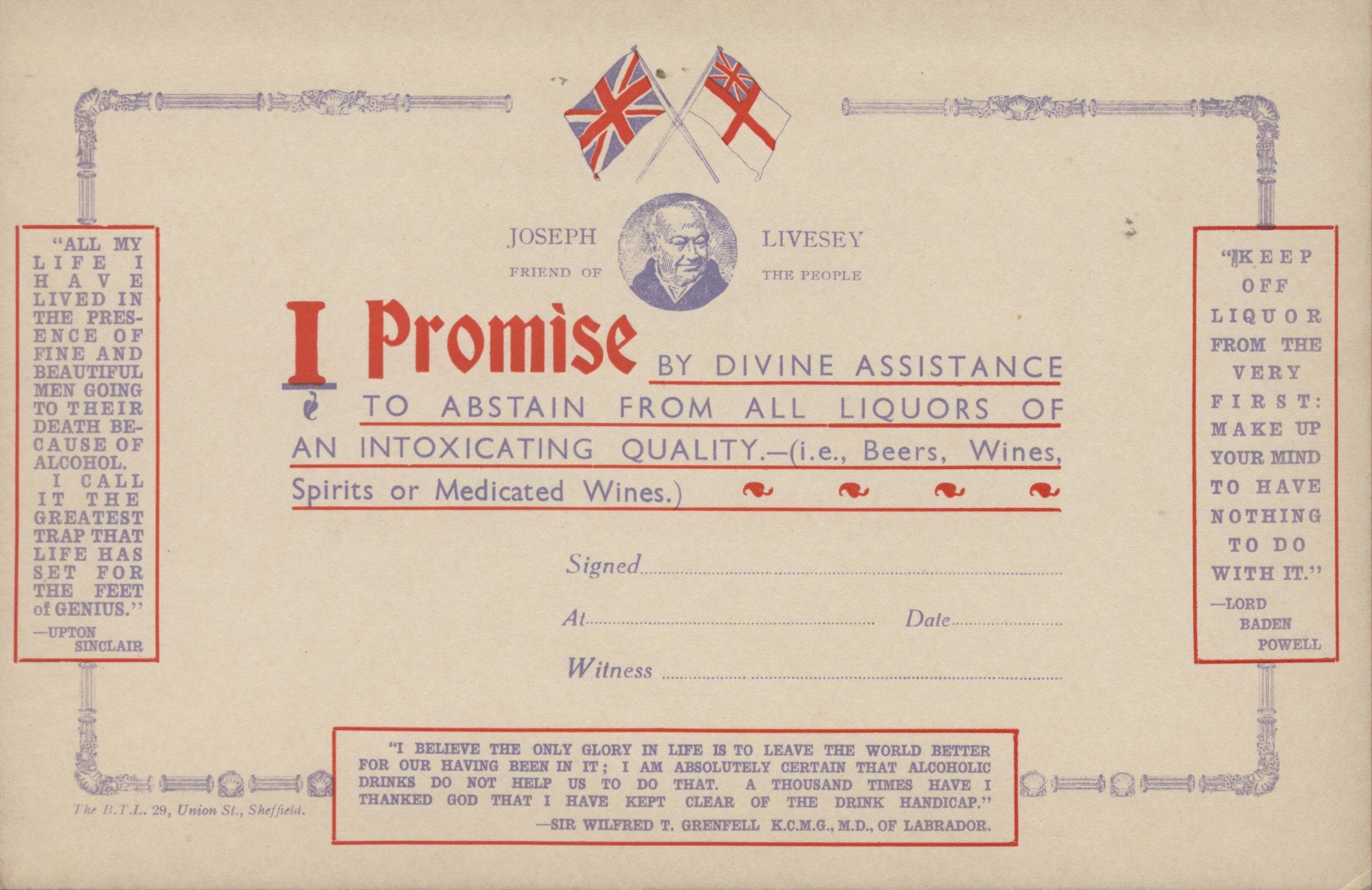

In 1832, a group of seven working-class men in the town of Preston, England, decided to take action. There were already a handful of middle-class temperance societies encouraging moderation, but this was different. Political radicals by nature, and led by the charismatic Joseph Livesey, these men were determined to help people escape the poverty and ill health they blamed on alcohol. They gathered to sign a pledge of total abstinence.

From this point, says McAllister, the movement “spread like wildfire.” Keen to evade both the demon drink and the capitalist power of the brewing companies, converts signed pledge cards to confirm their teetotal status. McAllister explains that their owners would often frame and hang the beautiful certificates. “It was not only a celebration of people having taken the pledge,” she says, “it was a reminder to keep to it.”

Livesey was quick to realize that once their initial enthusiasm subsided, reclaimed drinkers would also need an alternative social support structure. After all, 1830s England had few meeting places that didn’t revolve around boozing. In Preston, Livesey founded the first Temperance Hotel in 1833. Soon enough, other temperance venues—as well as clubs and events—appeared, all bolstering the resolve and sense of community of a growing teetotal population.

Temperance bars were probably less raucous than pubs. But the idea of them as dour, lifeless places is way off the mark. Whereas public houses often removed an adult from the family, the temperance bars were multigenerational spaces, where families would gather to read, discuss the newspapers, and sing temperance songs:

No matter what anyone says

No matter what somebody thinks

If you want to be happy the rest of your life

Don’t marry a man if he drinks.

According to McAllister, temperance and its associated bars fell from favor from the 1950s onwards. The emerging youth culture was more absorbed with consumerism and rock and roll than wholesome 19th-century social movements. “I think it just became deeply unfashionable,” says McAllister.

Yet for the few remaining adherents to the pledge, the symbolic importance of Mr Fitzpatrick’s has endured. Morley-Doidge has seen it herself. “When I first took over the bar five years ago, a man came in to celebrate exactly 50 years since he’d given up alcohol with a glass of sarsaparilla,” she recalls. “He’d taken the pledge in the bar.”

Made from a combination of roots and with a distinctive woodsy flavor, sarsaparilla remains one of the bar’s bestsellers. Another favorite is Mr Fitzpatrick’s blood tonic: a balmy combination of raspberry, nettle, and rosehip. As with many of the other cordials, it can be served mixed with hot and cold water or milk, or sipped down with soda. “It was made in the belief that it would be good for your immune and digestive system,” says Morley-Doidge.

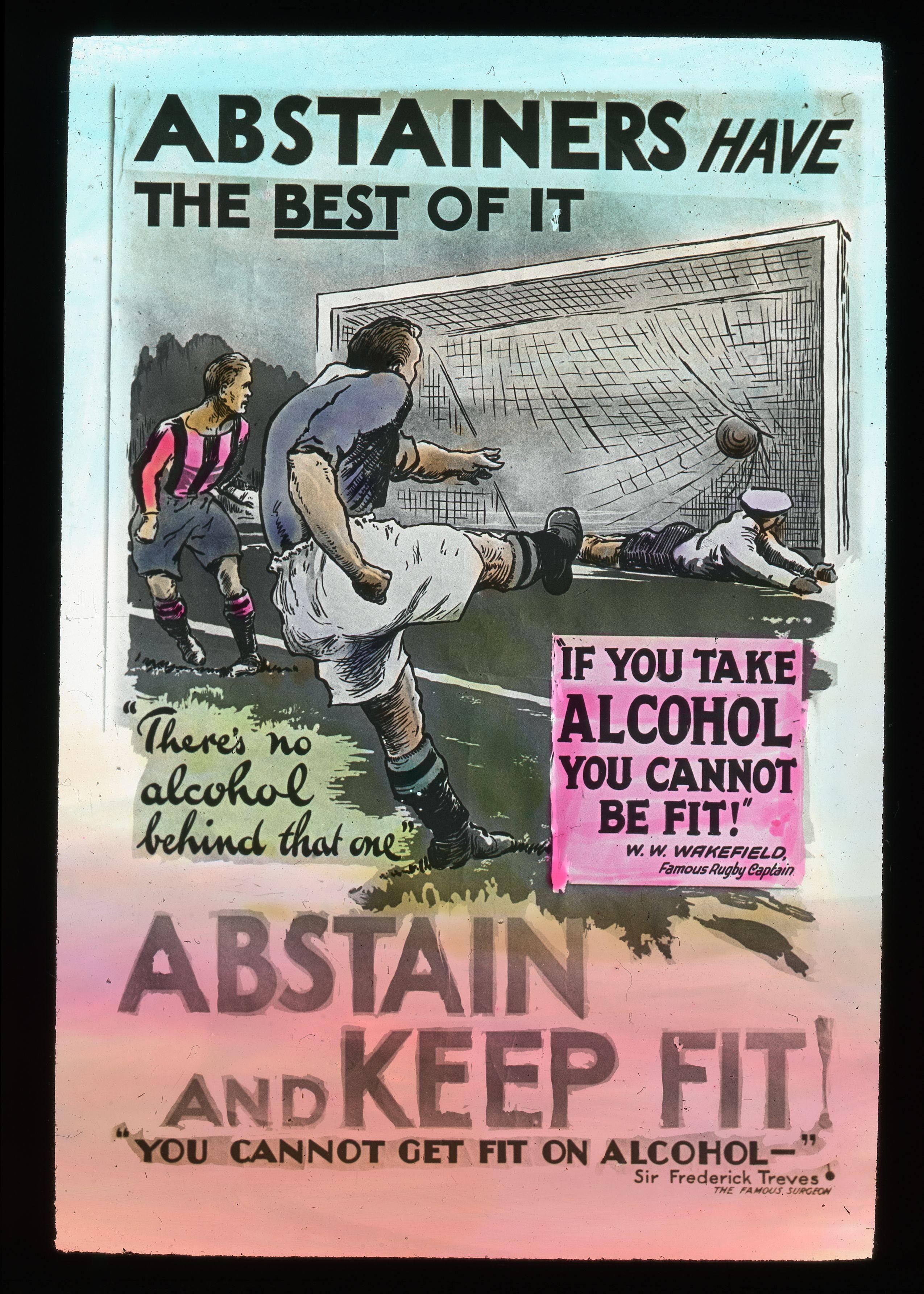

The temperance movement was keen to promote alcohol alternatives, especially when it came to children. “For most of the 19th century, it was not just legal but common to give children alcohol,” says McAllister. Some historical sources suggest that landlords lured children into pubs to spend their meager wages with the promise of cake.

For a time, Morley-Doidge also had to ponder how to bring young people back to Mr Fitzpatrick’s. “When I took over, I noticed it was an older generation coming in.” Not that it’s a current problem for the bar. Morley-Doidge has introduced a range of milkshakes using the traditional cordials as bases. “They’re very popular,” she says. “We’re now known to little ones as the milkshake shop.”

It isn’t just customers at either end of the age spectrum that are propping up Mr Fitzpatrick’s. Alcohol Change UK reports that a quarter of young British adults currently don’t drink alcohol at all. Morley-Doidge has seen this reflected in her growing clientele of teenagers and twenty-somethings. “They’re just not big drinkers. They fancy coming out for something that’s a bit different,” Morley-Doidge says. Her assessment is supported by increasing numbers of new dry bars in British cities. Interestingly, booze-free social scenes are often reported as a new trend, rather than one with roots back to 19th-century radicalism.

The bar only once came close to closure, when loyal patrons dwindled at the beginning of the 21st century. But Mr Fitzpatrick’s is once again central to the community it serves, with home deliveries during lockdown and a knitting collective making the bar their base. These days, there’s even an international clientele eager to buy blood tonic. Morley-Doidge is proud that Mr Fitzpatrick’s has proven so resilient. “This bar is this town’s heritage,” she says. “For us, it’s about keeping that heritage alive, and British heritage alive too.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook