The Epic Journey of an Exquisite Jade Pagoda

It started life as a jadeite boulder in modern-day Myanmar. Now it’s a celebrated part of a Chicago museum.

Almost a century ago, 150 Chinese artisans spent a decade carving and polishing a sculpture of unparalleled craftsmanship. They shaped miniature doors, balconies, and bells; they cut eggshell-thin chains and 400 uniform pillars. The finished piece, an exquisite jade pagoda, stands nearly five feet tall atop a teak altar.

Hundreds of thousands flocked to see this delicate work when it debuted in 1933, first at the Chicago World’s Fair and then in several other major American cities over the next two decades. Some described it as the Eighth Wonder of the World. But over the last 50 years, the pagoda has largely faded from public consciousness, having alternated between storage and a lower-level gallery in a California museum.

“This is the largest jade carving outside mainland China,” says Tongyun Yin, curator of Asian Art at the Lizzadro Museum of Lapidary Art in Illinois, which acquired it in 2018. “But sadly, not many people today know about it.”

Now, nearly 90 years after it was completed, the pagoda and its altar is on prominent display again. In November, the Lizzadro Museum reopened in a new building, in the Chicago suburb of Oak Brook, and introduced the sculpture as the centerpiece of its permanent collection. “This piece is of strong interest to us because of its size, technical mastery, and sophistication, but it also has a very strong, established provenance,” Yin says. “We know every detail about its life.” (The museum is currently closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, though its museum shop is offering curbside pickup.)

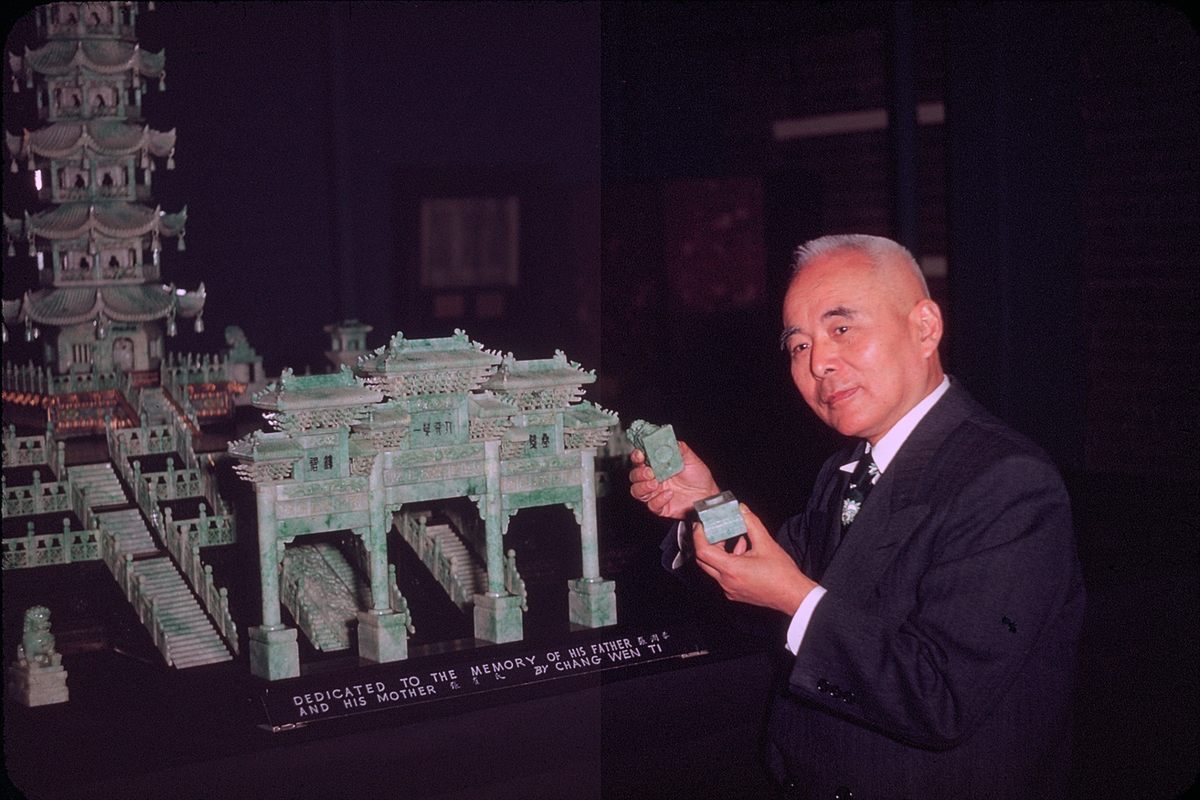

Known as the Altar of the Green Jade Pagoda, the gleaming artwork is the remarkable result of one man’s lifelong quest for perfection. Chang Wen Ti was born in 1886 in the Chinese city of Suzhou. In Shanghai, he became a master jade carver and collector who dreamed of creating the world’s finest jade sculpture. He wanted to show the potential of this treasured stone, which is traditionally used to make jewelry and other ornaments.

In 1915, Chang found his opportunity. A jade dealer won a bidding war over a record-breaking jadeite boulder from a quarry in present-day Myanmar, and he invited Chang to come see it. The stone was a stunning apple-green and weighed 18,000 pounds; the dealer had it cut into 13 pieces, and Chang chose the best five. Ox carts hauled the treasure, weighing 7,000 pounds in all, to Thailand and then Hong Kong, where it boarded a train to Shanghai.

With his material secured, Chang had to decide on a worthy subject. According to The Magnificent Chinese Jade Pagoda, a book by his daughter Mae Chang Koh, he aspired to replicate an unmistakably Chinese emblem of rest and peacefulness. “In his words, ‘Pagodas in China were built in memory of heroic people who became great because they championed peace and kindness,’” Koh recalled.

Chang traveled across China to observe the architecture of pagodas and record their best features. “He wanted his pagoda to be the epitome of all pagodas in design and beauty,” Koh went on. With support from investors, the carver recruited 150 of the best jade artisans to transform his prized stones.

The resulting pagoda and altar included more than 1,000 carved pieces and were finished in April 1933. The central tower resembles the ancient Lunghwa Pagoda in Shanghai in contour, but it reflects Chang’s own distinctive vision. It is hollow, so that light can enter and illuminate the majestic green tints, and each of its seven levels feature eight windows with intricate balustrades. From every corner of each sloping roof hangs a tiny bell carved from the same piece of jade as the eaves. Chains hang gracefully from the pagoda’s apex, and gleaming staircases and terraces surround its base. A 16-inch-tall, triple-arch gateway stands before it, flanked by two guardian lions.

The U.S. Consulate in Shanghai at the time, Julean Arnold, published a pamphlet about the pagoda to introduce it to the world. “In this wonderful collection, Mr. Chang has assembled what is probably the finest group of green jade works of art that has ever been produced throughout the four thousand years of jade craftsmanship in China,” he wrote.

By then, Chang’s commission was on its way to Chicago for display at the Century of Progress International Exposition, where visitors could even purchase souvenir pagoda postcards. That same year, it was disassembled and sent to New York City for an exhibition at Rockefeller Center, and then sent back to Chicago for the Exposition’s second year. In 1939, it traveled to San Francisco for the Golden Gate International Exposition, followed by a tour along the West Coast in the 1940s and 1950s, which raised funds for orphans of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Chang ultimately immigrated with his family to Los Angeles, where his reputation as a jade expert grew. In 1961, he died of a stroke, in the process of planning one more display of the pagoda at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. That journey never came to fruition. Seven years after his death, his family donated the Altar of the Green Jade Pagoda and Chang’s personal jade collection to the Oakland Museum of California, as a gesture of friendship between Chinese and American people—but a bitter battle ensued over its display. “The collection was never placed in an area it deserved,” Koh wrote in 2017. “Over 50 years of pleading, it has remained in the basement of the museum despite the requests of the family for it to be moved to a more prominent spot.”

In 2018, the Oakland Museum invited other American institutions with major jade collections to acquire the historic pagoda, and the Lizzadro Museum was chosen after a long process. Now, the Altar of the Green Jade Pagoda sits in a custom glass case, surrounded by other magnificent Chinese jade objects. The stately display marks the end of a decades-long, transcontinental odyssey. “It made its debut in Chicago, and now it has come back to what will be its permanent home,” Yin says of the pagoda. “It has kind of made its life circle.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook