The Curious Story of Wierszalin, a Belarussian Prophet’s 1930s Forest Utopia

Eliasz Klimowicz’s followers believed he was Christ reborn.

The church in Grzybowszczyzna Stara, built on the initiative of Eliasz Klimowicz in the 1930s. During World War Two, it became an Orthodox Church. (Photo: Krzysztof Kundzicz/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the mid-1930s, a prophet appeared in the woods of eastern Poland. He worked miracles and told the future. He attracted disciples from his fellow villagers, who became his apostles, and sometimes, his wives. His followers included peasants and farmers, as well as charlatans, pretenders and would-be tsars. Together, they built a church for the new faith. Then they began work on a city, called Wierszalin, which they believed would soon become the capital of the whole world. From a few people, it grew into a movement with hundreds of followers and its own idiosyncratic take on Orthodox beliefs.

Then the war came and swept it all away, leaving just a few scattered believers to keep the legend of the holy city alive.

The story of Wierszalin begins a few years before the First World War with a peasant named Eliasz (or Elijah) Klimowicz. He lived in a village called Grybowszczyzna Stara, located near what is now the Polish-Belarussian border. It was far from the main roads. The soils in the area were sandy and the farms poor. Włodzimierz Pawluczuk, the Polish journalist who chronicled the rise and fall of Klimowicz’s movement, titled his story “a report from the end of the world.”

Klimowicz first came to fame thanks to an expedient act of piety. A bandit who lived in the woods was preying on the farms around Grybowszczyzna. Klimowicz traveled to see a nearby holy man named John of Kronstadt to pray for help. While he was away, someone killed the bandit. Credit didn’t go to the killer, but to Klimowicz, for having the foresight to seek divine intervention.

Then came the Great War. The Russians evacuated the western borderlands in 1915, sending the local peasants deep into the Russian interior to deny the Germans access to their food and labor. For most, it was their first contact with the wider world. They saw new ways of being and thinking. Many took part in the Russian Revolution of 1917. But when they returned home they found that they no longer lived in Russia, but in the Republic of Poland. As Belarussians, they were members of a discriminated minority. As members of the Orthodox Church in a Catholic country, they belonged to a persecuted faith.

Something about this situation made a deep impression on Klimowicz. He became obsessed with building a church. To raise money, he sold all his land–something that was almost unthinkable in that time and place –and then he took to traveling in search of donations. Gradually, his fame grew. He worked miracles, curing the sick and casting demons out of the possessed. Then he began to preach.

He foretold the redemption of the world, and the people he met gradually began to believe that he was a prophet–the Prophet Elijah, returned to Earth. And then, finally, the rumor spread that he was Christ reborn, come to establish his kingdom in the Grzybowszczyzna woods.

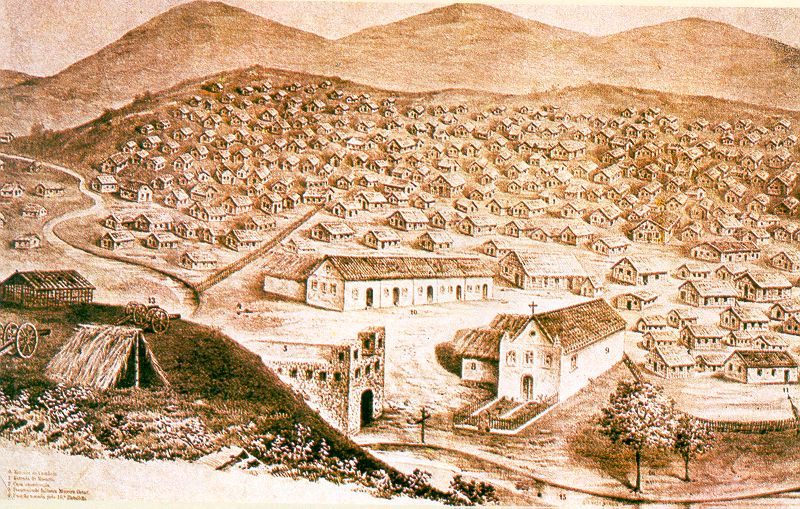

The settlement of Canudos, one of the many attempts to build a heavenly city on earth. (Photo: Public Domain)

From across the region people flocked to be near Elijah’s court, which he kept in an isolated farmstead a few kilometers away from Grzybowszczyzna, in a spot called Wierszalin. Men left their wives, women left their husbands. Widows and virgins proved especially keen to join the movement. Regular people suddenly found themselves thrust into biblical roles. Pawel Bielski, the son of a cloth dealer, became the Apostle Paul, writing down Elijah’s deeds and praising them in hymns. Aleksander Daniluk, a lumberjack and day laborer, became his Apostle Simon. They believed that Wierszalin would soon be the greatest city in the world. The alleys between the trees in the neighboring woods were going to be its streets. A clearing by an old oak tree was going to be its central square, the center of the Earthly Jerusalem.

Why were people so quick to believe in Elijah? In one sense, nothing about his arrival was that far out of the ordinary. The history of Russian Orthodoxy is full of schisms, sects and redeemers. In the 17th century, a man named Ivan Suslov declared himself the son of God. According to tradition, almost certainly false, he was crucified twice in front of the Kremlin and twice rose from the dead. The second time he was skinned alive, but a young girl covered him with a sheet, which clung to his body and became a second skin. Suslov went on to be one of the founders of the Khlysty, of flagellants, who believed that Christ was periodically reborn, and that there were many such ‘Christs’ on Earth at any given time.

One such Christ was named Kondraty Selivanov. In the late 18th century, he announced that the way to salvation lay in renouncing the sinful flesh. He castrated himself and recommended that his followers do the same. Thousands did, and Selivanov’s sect, the Skoptsy, or castrators, lasted into the 20th century, believing all the while that their founder was still alive, wandering the earth disguised as a beggar and waiting to reveal himself on the appointed day of Judgment.

Klimowicz may have been the last in a long line of peasant Christs. But the reason for his appeal likewise reflected his moment. Over the course of his life, the people of the Belarussian borderlands had seen war and revolution, the world had been turned upside down. Sometimes it seemed as if all the prophecies in the Book of Revelations had already come to pass.

Speaking years later, Aleksander Daniluk, who served as Elijah’s apostle Simon, explained it like this:

“All the prophecies in the Bible had already been fulfilled, Christ’s return included. Above the world blazed the star foretold by the prophets–the red star, the star of the revolution, the star of the Soviet Union! All we had to do was tell people of this truth, so they would understand, that life was not ordinary life anymore, but the fulfillment of the greatest prophecies.”

The countryside around Grzybowszczyzna, where Klimowicz sought to establish his kingdom. (Photo: Krzysztof Kundzicz/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Wierszalin, the end of days was near, or, it had already happened. Time, normally confined in narrow channels, began to run wildly in every direction. In the village of Ciełuszki, Olga D. ran through the streets naked smashing windows and yelling ‘Repent!’ to all who would hear. Jana D. toppled crosses at the cemetery, broke fences and smashed windows with her bare hands, shouting “An end to everything old!”

Disturbed by her outburst, Elijah’s followers chained Jana to a wall with an iron chain. On festival days they sang hymns to her even as she insulted them with foul names. They still considered her holy, among other reasons, because in the span of 34 days, she ate only three times. A number of other women became “mothers-of-god,” since if Christ was truth, whoever proclaimed truth gave birth to God. At least one mother-of-god lived with Elijah under his roof.

Elijah foretold the redemption of the world. Soon, a group of pretenders and would-be emperors arrived in Wierszalin, likewise promising a return to the old order that had been lost in the war. First came a man claiming to be Tsar Nicholas II. He lived in an old monastery and sewed shoes. He painted icons too, and his tsarina sold them on street corners, before they revealed their true identities and became the toast of a hundred feasts. Next came someone who said he was the son of Emperor Wilhelm II arrived as well, promising to rebuild the German Empire with its new capital in the village of Ciełuszki, but he vanished without a trace. Finally, another pretender-Tsar appeared, 40 kilometers away. Many believed that he too was Nicholas Romanov come back from exile. He was old though, and always drunk, and after a time he dropped his royal pretensions and joined the Wierszalin choir.

Wierszalin’s heyday only spanned a few short years. Its end began, suddenly and dramatically, in the summer of 1936. It was harvest time. A procession of peasants made its way through woods on sandy tracks to the Prophet’s seat. A man at the head of the parade carried a wooden cross. Another, a whip. A third, a crown of thorns made from a length of barbed wire. Someone else brought a hammer and several long, square nails, specially-forged, the kind they used to stage the crucifixion at Easter.

Opinion remains divided whether the pilgrims came to give the cross as an offering to Elijah, or if they meant to crucify him to help bring about the end of days. He seems to have assumed the latter. Before the procession’s chosen Judas had a chance to kiss him, Elijah fled. He hid in one of his farm’s root cellars, covering himself in straw. After three days, he emerged, as if from the dead, but it was not the kind of resurrection his followers were hoping for.

Elijah’s fall began as farce, but it ended in tragedy. In 1939, war came again to Wierszalin. When the Soviets came, it is said that Elijah was denounced by one of his own apostles. The Russians laughed at him, calling him the “Polish God.” According to one report, Klimowicz was killed on the spot. According to others, he was deported to Siberia, where some believe he preached for many more years. Some say he died of old age in a nursing home in a converted monastery near Krasnoyarsk. No one knows for sure.

The back of the church. (Photo: Krzysztof Kundzicz/CC BY-SA 3.0)

After Elijah’s death or disappearance, most of his followers abandoned belief in the prophet. A few, though, kept his memory alive. Włodzimierz Pawluczuk, the journalist who spoke to most of the surviving believers in the early 1970s, describes a few of their fates. The apostle Simon, who remained faithful, sold pears in the town square. Paweł Toloszyn, who helped Elijah build the Wierszalin church, returned to his farm and became an inventor of labor-saving devices.

In Elijah’s time, Miron was the archangel Gabriel in the Heavenly Court. He rode a white horse, and played a silver trumpet on which he announced the end of the world. Thirty years later, he was a beekeeper, one of the best in the district. A woman named Pałaszka was once one of Elijah’s mothers-of-god, and one of his fiercest defenders. One Easter, confronting an Orthodox priest who doubted Elijah’s divinity in his own church, she had barred his way, yelling, “The Holy Book is not for you to read, blood-drinking wolf!” She later became one of the area’s most noted weavers; in 1970 she wove a rug in honor of Lenin’s hundredth birthday.

This small group of believers kept Elijah’s sect alive in the decades after his disappearance. Every year they would return to Wierszalin and visit the holy hill of Grabarka, and next to it the valley of Jehosaphat. Afterwards, they would meet in Wierszalin’s sole remaining house to recite prayers and sing songs lamenting their lost Paradise.

These followers kept photographs and other relics from the days of the movement’s glory. In one photograph, Elijah stands next to a village mayor. Wearing a homespun shirt, with a medal pinned to his chest, he looks like a village postman. His eyes don’t burn. His sight doesn’t probe any unearthly distance. His gaze is forthright and direct. On another, someone has painted a halo around his head with a broad white stroke. It makes Elijah look like the center of a target, floating toward a destination only he can see.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook