The Worst Freelance Gig in History Was Being the Village Sin Eater

Sin eaters risked their souls to soak up the misdeeds of the dead.

When a loved one died in parts of England, Scotland, or Wales in the 18th and 19th centuries, the family grieved, placed bread on the chest of the deceased, and called for a man to sit in front of the body. The family of the deceased watched as this man, the local professional sin eater, absorbed the sins of the departed’s soul.

The family who hired the sin eater believed that the bread literally soaked up their loved one’s sins; once it had been eaten, all the misdeeds were passed on to the hired hand. The sin eater’s own soul was heavy with the ill deeds of countless men and women from his village or town—he paid a high spiritual price for little worldly return. The coin he was given was worth a mere four English pence, the equivalent of a few U.S. dollars today. Usually, the only people who would dare risk their immortal souls during such a religious era were the very poor, whose desire for a little bread and drink outweighed such concerns.

As early as the 1680s these morbid local feasts were written of as an “old Custom at funerals,” and the practice survived into the early 20th century. According to Brand’s Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, first published in 1813, the sin eater “sat down facing the door; they then gave him a groat, which he put in his pocket; a crust of bread, which he ate; and a full bowl of ale, which he drank oft’ at a draught; after this, getting up from his stool, he pronounced, with a composed gesture, ‘the ease and rest of the soul departed,’ for which he would pawn his own soul.”

Many funerals in the Welsh county of Monmouthshire included a professional sin eater, author Catherine Sinclair notes her 1838 travelogue, Hill and Valley. Her description of the job gets harsh when she adds that the men “who undertook so daring an imposture must all have been infidels, willing, apparently, like Esau, to sell their birthright for a mess of pottage.” To those who believed in the powers of this ritual, sin eaters were doing a necessary but distasteful job, literally becoming a bit more evil as they performed their task.

Sin eating had experienced a decline by the time Sinclair observed the practice in Wales, but the last recorded sin eater, Richard Munslow, briefly brought the custom back in the late 19th century. In the travel guide Slow Travel Shropshire, Marie Kreft explains that Munslow revived the practice not because of desperation, but due to sadness. He was a successful farmer who suffered the loss of four children, including three in a single week. It’s speculated that this tragedy drove him to practice the sin-eating trade, at first as a form of grieving, to help his children on into the afterlife.

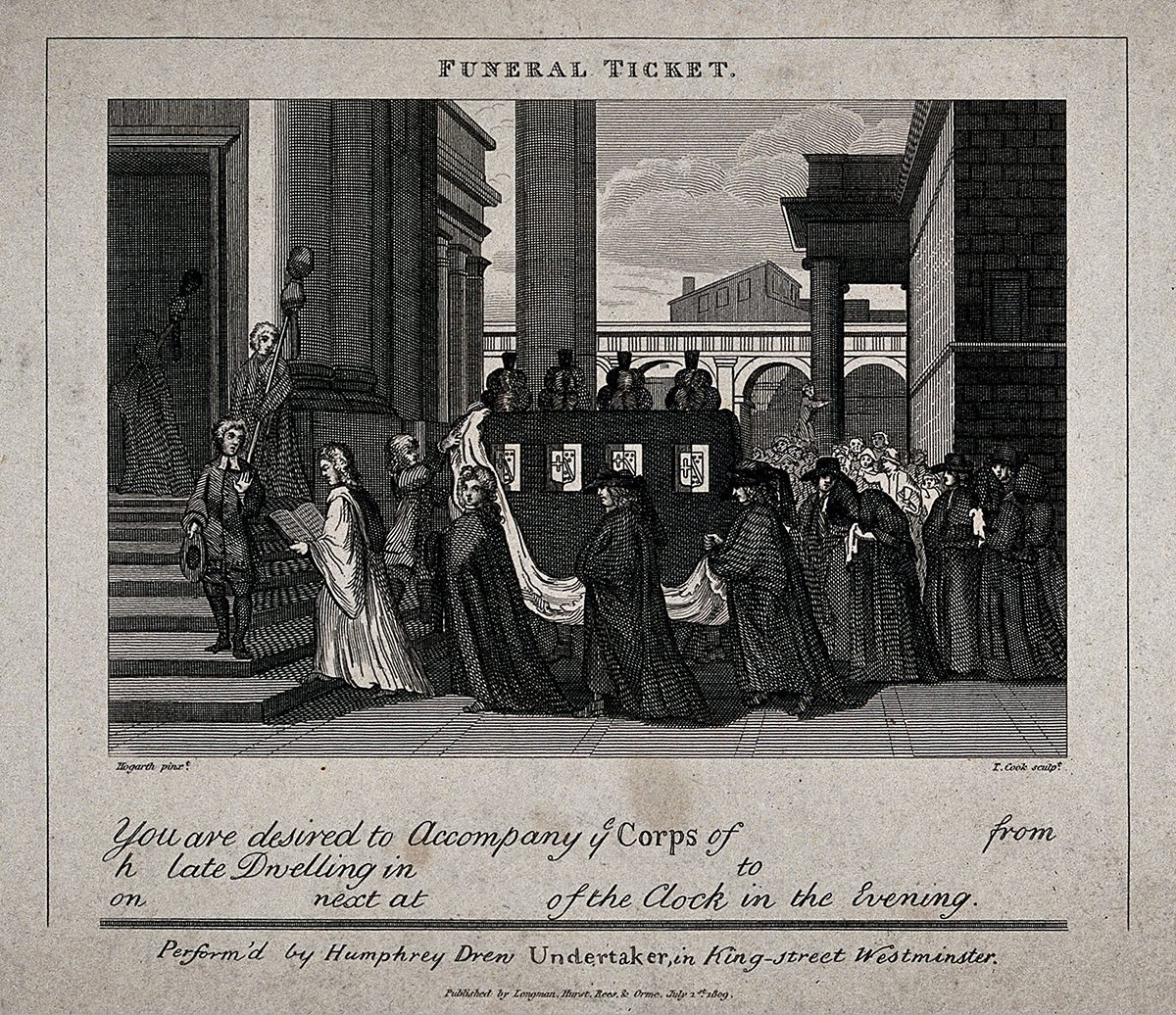

The god-fearing villagers who hired sin eaters in the profession’s heyday, however, wanted to skirt the consequences of their sins (and those of their loved ones) by giving them to someone else, and adapted their own morals to accommodate the practice. Because of the religious climate of the time, people took the idea of sin seriously, and were eager to reach heaven free of their misdeeds. They needed a sin eater to come around every once and awhile, but most of the time being a sin eater meant you were homeless and a social pariah. Nevertheless, sin eaters in the United Kingdom were expected to attend funerals and wakes when they were notified of a local death.

The origin of sin eating is elusive, but the custom may have grown from older religious traditions. Historically, scholars believed it came from pagan traditions, but in Death, Dissection and the Destitute, Ruth Richardson writes of a medieval custom that she thinks may have developed into sin eating; before a funeral, nobles once gave food to the poor in exchange for prayers on behalf of the recently deceased.

In the 18th century, rituals involving symbolic breads, which represented the souls of the dead, were fairly common and may connect to sin eating, too. Antiquarian Henry Curzon wrote in 1712 that villagers in the English county of Herefordshire hired “poor people to take on them the Sins of the Deceased,” yet also piled cakes in “high heaps” on tables to honor their dead loved ones for the Catholic holiday All Souls’ Day, on November 2.

In her essay The Gift of Suffering, Ingrid Harris writes that Protestant practice may have used sin eating to regain the lost sacraments from its Catholic roots. In fact, many sin eaters listened to confessions from grieving families. Sin eating was not officially supported or sanctioned, however, and Richardson argues that using a sin eater bestowed human power over spiritual events, which would have been considered heresy.

Calling a sin eater might also have meant that the local priest, who normally would have coaxed the soul to heaven and performed a funeral ceremony alone, was overlooked. Over time, fewer sin eaters took on the mantle, restoring priests to their traditional role. By the early 20th century, sin eating had mostly died out.

Sin eaters may have stopped plying their trade, but according to Jane Aaron’s book Welsh Gothic, they continued to eat sins in literature, and were used to explore various forms of Welsh identity. In these texts the sin eaters were always reviled. A narrative poem from 1920 features a sin eater called Morgan who is described as “gaunt, ghastly, lean and miserably poor,” and was later found dead as if struck from a bolt of lightning. In the United States, the concept of sin eating made its way to communities in Appalachia, where it survived as legends about nomads who roamed the countryside, looking to absorb dark and powerful sins.

The last known sin eater in the United Kingdom, Munslow, died in 1906. Though it took some time, he was likely one of the first of his profession to be commemorated with a ceremony and funeral of his own—in 2010 in Ratlinghope. While it’s unlikely that anyone was able to consume his heavy burden of sins as a bready meal, at least he was finally served something he and many other sin eaters deserved—recognition.

This story originally ran on November 22, 2016.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook