How Historians of Modern Tattooing Explore a Long-Hidden Past

The growing field probes everything from family collections to problematic museum exhibits.

One of the challenges facing tattoo historians today is that many owners of historically significant material—from actual pieces of preserved human flesh to suggested patterns, some of them a little grotesque—don’t come forward to share their finds, out of fear that scholars and the public would dismiss the subject as superficial or repulsive. Undeterred, every year these historians are probing ever deeper into inking traditions worldwide. They are documenting rare tools and designs and uncovering provenance trails of tattooed body parts that were put on public display—often amid great controversy. While the modern practice of tattooing itself has gained wide appeal, its multifaceted, multicultural origins and dark sides are still being exposed.

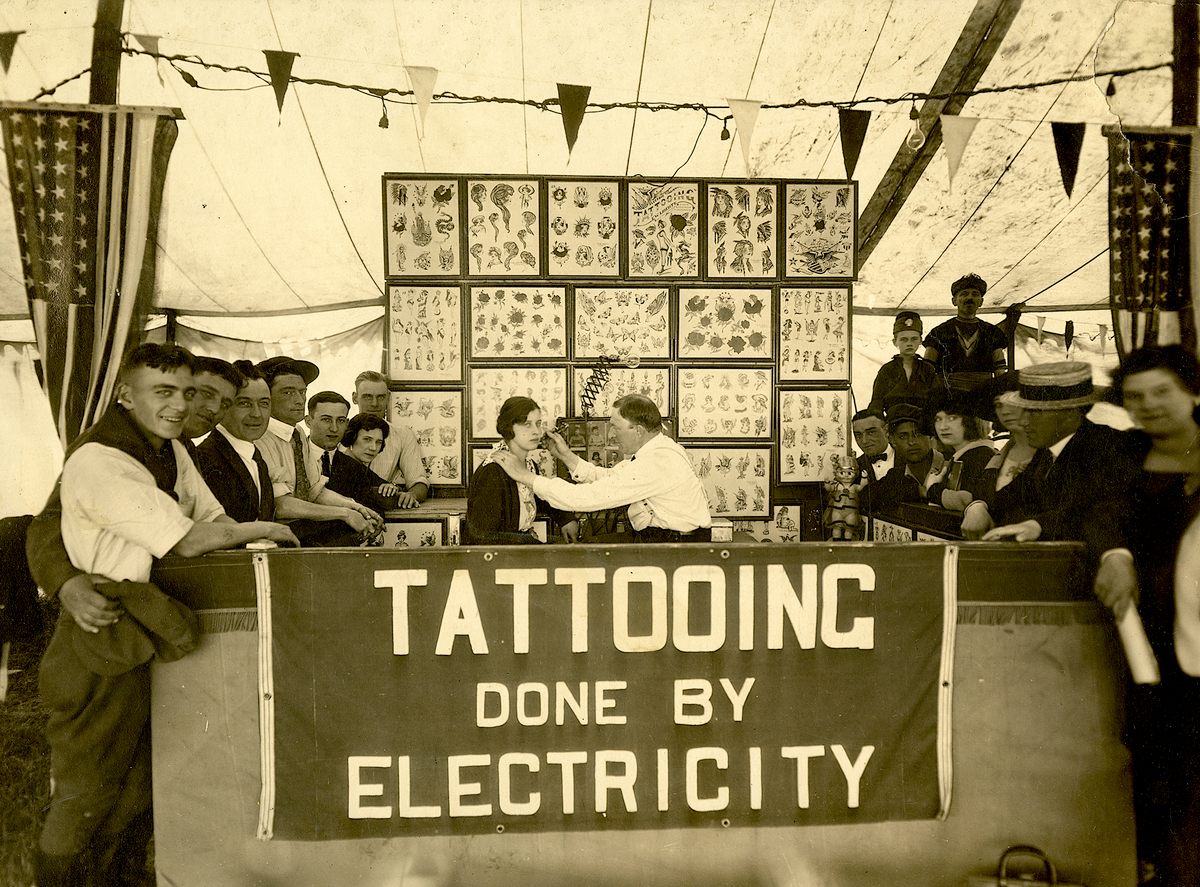

“People are curious about it,” says Margaret Hodges, coauthor, with fellow historian Derin Bray, of Loud, Naked & in Three Colors: The Liberty Boys & The History of Tattooing in Boston. From the 1910s to the 1960s, generations of the Liberty family ran tattoo parlors in downtown Boston, catering to sailors and socialites alike. Hodges and Bray’s densely footnoted book places the family’s trade in the context of harbor towns from Baltimore to Vancouver, particularly wherever military ships were docked. Liberty tattooists advertised pattern repertoires (known in the trade as “flash”) depicting everything from nurses to gravestones, athletes to demons, and martinis with racehorses labeled “Ruin of Man.” Portraits of female vixens were rendered “loud, naked and in three colors,” one Liberty tattooist told a Boston newspaper in 1947, as reporters documented the industry and its postwar decline.

The family also developed some sidelines over the years to insulate them from the ups and downs of the industry: farming, and raising lovebirds, goats, and chickens. They had brushes with the law, too, for charges including tattooing underage customers and using unclean needles. Liberty descendants—a dozen are widely scattered—were at first reluctant to share their stories and artifacts with the historian team. Bray notes that the family “was a little skeptical at first, but they eventually warmed to us when they realized we had good intentions.”

Heirlooms collected over the years have included consent forms for removal sessions. When Liberty customers developed buyers’ remorse, the artisans offered chemical removal potions with names such as Ridzem, formulas laced with vinegar, bleach, and mercury. On a 1950 example, which includes an actual X-shaped scab formed when the removal process caused peeling and bleeding, handwritten Liberty notations show that the client paid $35 for “tattoo off left fore arm. Skull cross bones.”

That haunting artifact—including the dried, coagulated portion of it—is part of a trove of Liberty material amassed by tattoo artist Lyle Tuttle. (Other tattoo practitioners with comprehensive ephemera collections include Don Ed Hardy, Henk Schiffmacher, and Chuck Eldridge.) Bray notes that he and Hodges have scoured dozens of institutional collections and that the field, although still new, “has definitely gained gravitas.”

As if to make that clear, last year, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, acquired Battleship Kate, a painted statue of a bikinied, tattooed woman made in the 1930s out of papier-mâché and fabric bits. It originally served as a storefront advertisement for Virginia-based tattoo artist August Coleman. (In 2014, the sculpture had made headlines in the tattoo and antiques press when it was sold at Skinner auction house in Boston for $28,290.) And in 2022, a Liberty retrospective will appear at the Eustis Estate Museum in Milton, Massachusetts.

But the road to legitimacy as a cultural phenomenon and art form hasn’t always been smooth. Robert K. Paterson, a legal scholar in British Columbia, shines sometimes unflattering light on museum and collector interest in tattooing with Tattooed History: The Story of Mokomokai. Starting around 1770, visitors to New Zealand, for example, began acquiring mokomokai, the desiccated heads of tattooed Māori. These objects appealed as souvenirs to American and European adventurers, scientists, and even freakshow operators, while missionaries decried them as a “disgusting commodity.”

Tattooing runs deep in Māori culture. They traditionally used bone blades to create channels in the skin and then tinted the incisions with soot and fat. The texturing survives postmortem. Some mokomokai had been wrested from the corpses of wartime enemies, as revenge trophies. Others had belonged to loved ones, and were meant to offer comfort to the living. Trigger warning for the squeamish: Do not read the rest of this paragraph if you do not want to know how the heads were made to last. The process involved gutting, steaming, baking, drying, stuffing, and oiling.

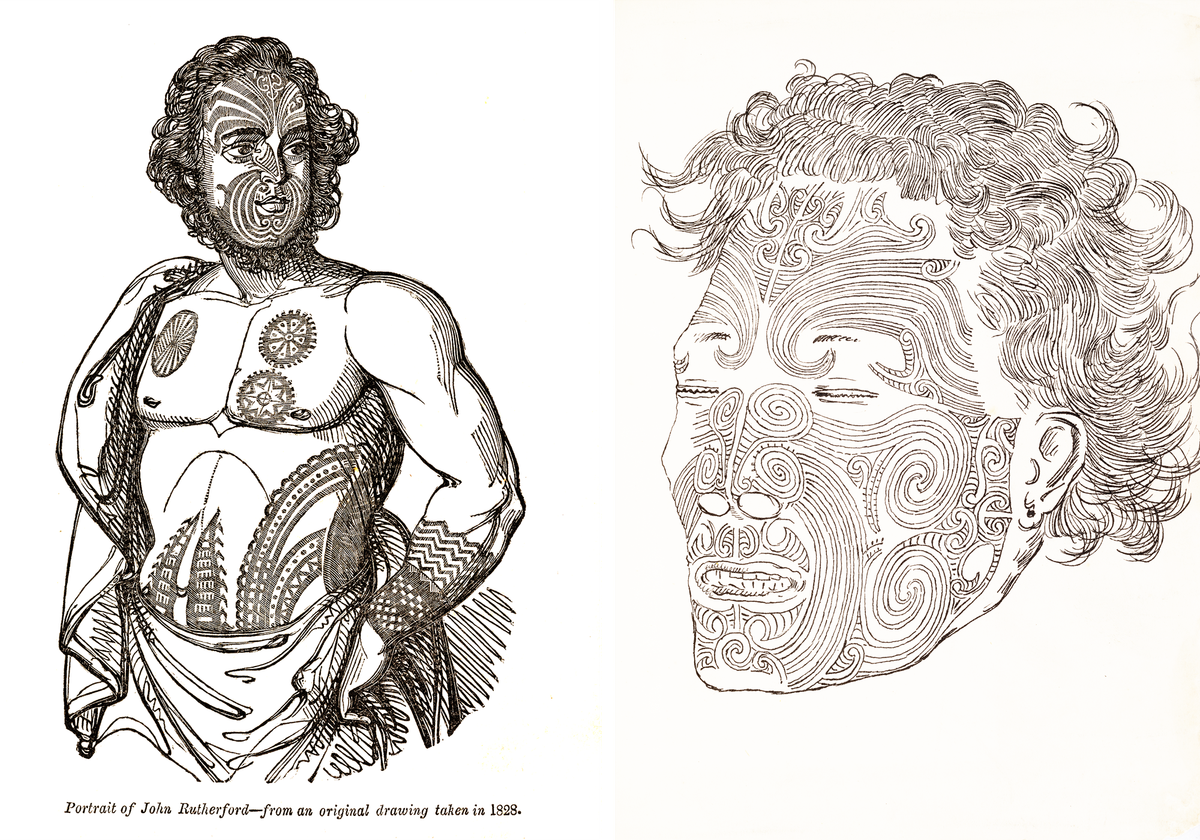

Some foreign visitors to New Zealand had their own faces and bodies covered in the tattoos. In the 1820s, a British sailor, John Rutherford, married two Māori women in New Zealand and then returned home densely marked in Māori starbursts, arcs, and chevrons. While pursuing professions including pickpocketing, Rutherford “would charge people to look at his tattoos,” Paterson says.

Until the 1830s, when the export of the dried heads was first controlled, some Māori themselves traded mokomokai with Westerners for weapons. As the body parts were resold again and again overseas, they made appearances in fiction as well. In Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, Queequeg has gathered mokomokai to sell as “great curios, you know,” the Massachusetts innkeeper Peter Coffin tells Ishmael.

Paterson has traced two centuries of ocean journeys of mokomokai. In 2014, the American Museum of Natural History returned a group to Te Papa, New Zealand’s national museum, where they are kept off view. In fall 2020, two others were sent to Te Papa amid ceremony by the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, where they were long generically labeled VI 2559 and VI 23649. The last public auction offering (canceled amid outcry) was in 1988, at Bonhams in London. A child had found a mokomokai in the attic of a country house and began combing its hair, before the family realized that it was not a toy.

Paterson writes that the trade has since gone underground: “Any transactions involving mokomokai would today be conducted in secrecy.”

Jamie Jelinski, a visual culture historian based in Canada, faced bureaucratic opposition while researching how five snippets of tattooed human skin—four rectangles and a trapezoid—ended up long on exhibit at the Musée de la civilisation in Quebec City. The images on flesh, outlined in faded blue-black with patches of red, include hearts pierced with daggers, clasped hands, a female sailor, and a billowing American flag alongside the cursive initials “M.B.” That latter piece was taken in 1929 from a 28-year-old murder victim, Mildred Brown. A native of Nova Scotia, she had been living in Montreal and was on a daylong bender when a waitress friend, Dorothy Campbell Morrison, known as Nancy, fatally bludgeoned her with a wooden beam.

No one knows why Wildred Derome, a physician and government forensics expert, kept some of Brown’s flesh; Morrison immediately admitted guilt, so there was no need for criminal investigation. The sources of the four other samples have not yet been identified. The specimens were later “nailed to a piece of vinyl that was then fastened to a wooden display plaque,” as Jelinski writes in a chapter of a new essay collection, Museums and the Working Class.

Derome’s other macabre souvenirs included “bones, internal organs, parts of men and women’s reproductive systems, and fetuses at varying stages of development,” Jelinski adds.

Last year, as Jelinski intensified his inquiries about the vinyl-mounted skin samples, government agencies relegated the tattoos and related documentation to deep storage. He has sued to continue his research, and legal proceedings are ongoing. “I’m extremely persistent—I’ll see this through to the final conclusion, win or lose,” he says. He adds that the stymieing campaign itself has made for interesting writing topics.

He is finishing a book provisionally titled Needle Work: A History of Commercial Tattooing in Canada and Beyond. He has gained access to forgotten family archives in garages and attics, as well as dozens of institutional archives, while researching the subject “as holistically as possible.” Throughout the 20th century, municipal authorities across Canada had tried to ban tattooing, portraying the parlors as dens of disease and immorality, yet the artisans and customers came from a wide variety of backgrounds and socioeconomic levels. “We have such a partial view of tattoo history,” Jelinski says. During the last decade, the field has attracted “academics across disciplines.”

Lars Krutak, a tattoo anthropologist, reports that the subject “is finally getting the attention it deserves” in comprehensive books such as The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Body Modification, due in 2023. Bray and Hodges’s new book, Floating West: Antique Japanese Tattoo Flash from the Collection of Nick York, is based on a handmade album that surfaced a century ago in Little Rock, Arkansas. No one knows how this collection of realistic Japanese tattoo patterns—dragons, snakes, geishas, butterflies, cranes, spiderwebs, a three-masted sailing ship—made its way to the United States.

The cover is wrapped in kimono fabric, printed with plum-colored plaids and flowering vines, and the creamy pages are silk. The images were produced when tattooing was largely banned in Japan. About five other examples of such albums are known to survive. Japanese practitioners would have offered the designs to tourists, “mostly moneyed white people,” Bray explains.

Blurry kanji markings on the cover shed no light on the book’s origins. Bray is hoping that signed versions of the maker’s work will emerge. “The style’s distinctive enough,” he says, “that we’d recognize it right away.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook