Space Chess Is Here, But No One Is Playing

The three-dimensional version of the game was around long before Star Trek.

If Lieutenant Commander Spock is known for one thing, it’s his signature Vulcan handsign for “Live Long and Prosper.” But if he’s known for a few more things, one of them is definitely his mastery of three-dimensional chess.

Though the board game may look like a sci-fi creation, 3-D chess is actually something that exists on planet Earth—and it was invented many decades before Star Trek.

Three-dimensional chess can refer to any type of chess in which the pieces can move vertically as well as horizontally, usually across a series of stacked boards. Most famously, this variant has appeared as a part of the Star Trek universe, where it is usually referred to as Tridimensional Chess. “I thought, ‘Hm. Interesting.’ But I didn’t pay much attention to it,” says Dr. Leroy Dubeck, President of the U.S. Chess Federation from 1969-1972, when Bobby Fischer won the world championship.

But while the prop designers who came up with Star Trek’s multi-level chess game probably just envisioned it as a futuristic kind of advanced strategy game, an actual version of three-dimensional chess has existed since at least the early 19th century.

Possibly the first version of three-dimensional chess was a German game, created by a doctor, occultist, and sometime inventor named Dr. Ferdinand Maack. In the 1900s, Maack worked on versions of three-dimensional chess throughout his life, later collaborating with his son on variations of the game, with at least one lost variant featuring game pieces fashioned after an okapi. Today he is best remembered for Raumschach, which ironically translates to “space chess,” although the futuristic association with three-dimensional chess wouldn’t come until later.

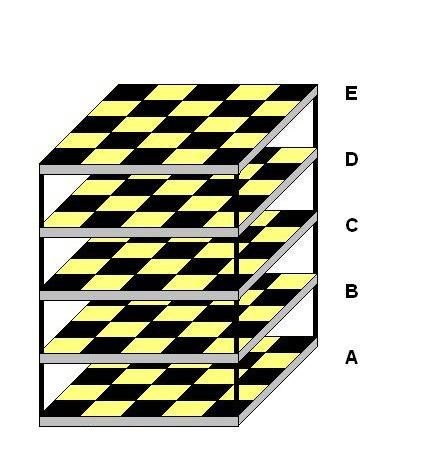

First unveiled around 1907, the game was inspired by Maack’s belief that if chess were to represent the strategy of actual warfare, then there must also be a representation of aerial and underwater attack, which could be represented by movement up and down a stack of playing fields. After some experimentation, Maack decided that the most effective configuration for the game was five 5X5 chess grids stacked in a tower.

Players start with their pieces lined up on opposite ends of either the top two tiers, or the bottom two. All of the traditional chess (sometimes called “orthochess”) stations are represented—king, queen, bishop, rook, and pawn—but there is also a special piece called the unicorn, the movement of which is tailored to a three-dimensional space. While the other pieces move in an approximation of their same pattern in two-dimensional chess, the unicorn moves diagonally and vertically through the corners of the squares. The win condition of the game is the same as in orthochess: to put the opponent’s king in check, with no further legal moves. It’s just far more difficult.

Unfortunately, despite Maack’s belief in the game, Raumschach never took hold. Dubeck, a lifelong chess master had never even heard of it. But three-dimensional chess, at least in the popular imagination, was far from dead. Other types of tiered chess games have been proposed over the decades, but none saw much popular or commercial success. Save for the fictional version aboard the starship Enterprise.

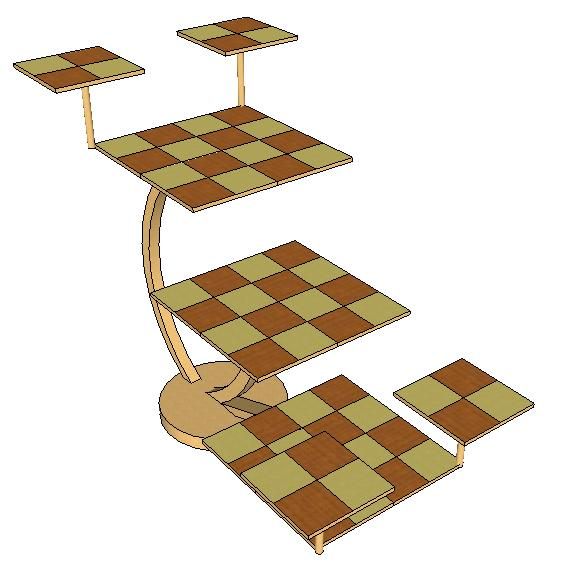

In the first season of the original Star Trek, Tridimensional Chess was introduced as the popular game of the future. In the episode “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” the very first scene presents Captain Kirk and Lieutenant Commander Spock as they play a familiar but multi-tiered game that Kirk simply calls, “chess.” The board is split into flying tiers of different-sized grids, and it certainly looks like a set of chess from the future.

The game reappears in subsequent episodes of the series, and a similar but even more futuristic version shows up on Star Trek: The Next Generation. No gameplay guidelines were ever set down on screen, but fans and experts began to create their own rules for the game by the late-1970s. The rules of Tridimensional Chess differ from author to author, but many have gone to great lengths to make the strange board work as a serious chess variation. Some ambitious players have even created variations of “standard” Tridimensional Chess, with in-jokey names like “The Borg Queen,” “Warp Factor,” and “Kobayashi Maru.”

Dubeck himself even worked on a version of official rules to accompany a licensed replica of the game, although the only thing he really remembers about them is that they weren’t exactly tournament ready. “Anyone who’s actually interested in chess, they’re going to want to stick with the usual board,” he says. “The purpose of this would be to sell it to Star Trek fans who would want it sitting at their table, to show off that they got a set.”

Given the continued experimentation with three-dimensional chess variants, as well as the popularity of Tridimensional Chess (even as a prop), why hasn’t the variation taken off? Where are the international three-dimensional chess tournaments? How come Tridimensional Chess hasn’t seen a Quidditch-like league spring up among fans and players (beyond something like this small Facebook group)?

For the most part it has to do with a lack of other players or availability. Given the extreme challenge of mastering a game like three-dimensional chess, there is almost no professional payoff, other than love of the game.

According to Dubeck, becoming a 3-D chess wiz could even make you worse at traditional chess. “If you start fooling around with something three-dimensional, it may be confusing your mind while playing at regular chess, so it may actually work negatively,” he says. “Therefore, why should I spend time on something I can’t use, which in fact may make me a worse chess player?”

Dubeck isn’t confident that a major chess variation will ever truly take off, due in large part to the struggle to make it commercially viable. Respectfully, doctor, Spock would disagree.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook