A Photographer’s Ode to Everyday Soviet Architecture

Arseniy Kotov finds inspiration in urban exploration and concrete cityscapes.

Concrete is a common, humble material—sand, gravel, and cement—but Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev sang its praises for the better part of a passionate, detailed, two-hour speech he delivered to an industrial conference in 1954. He proposed that concrete should be used for anything and everything, especially prefabricated and standardized buildings that would help accelerate construction and development. It was, he argued, absolutely vital to the Soviet project. The subsequent boom in mass housing was described by The New York Times in 1967 as an “architectural sputnik.” (Though the piece did also state, “There is no real style in Soviet cities yet.”)

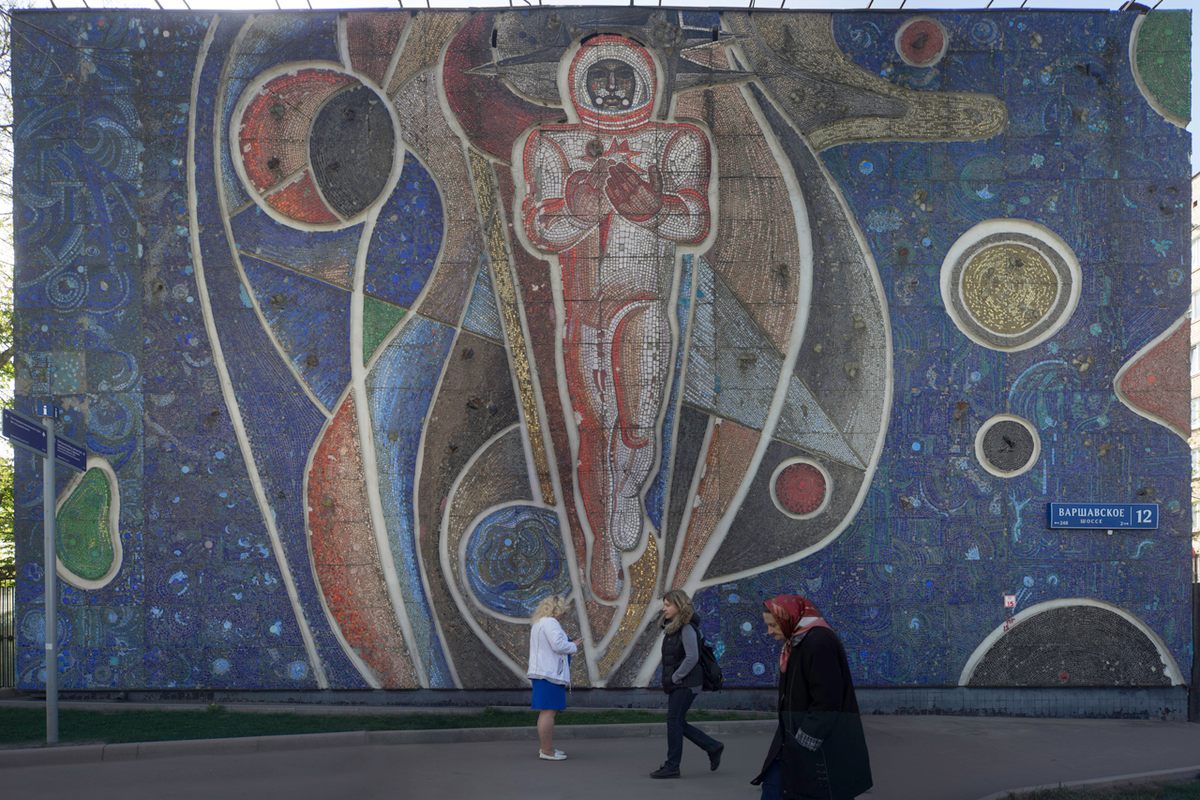

Concrete is abundantly present in the contemporary cityscapes of Russian photographer Arseniy Kotov. Images from his upcoming book, Soviet Cities: Labour, Life & Leisure, often depict rows and rows of high-rises, marching endlessly across the horizon. Yet within the cold-looking concrete blocks, he also manages to capture the warm glow of life in apartment windows.

Kotov was born in 1988, so he did not experience much of Soviet life, but he admires the period’s “great civilization” of architectural and cultural heritage. The country is changing fast, but nostalgia for Soviet aesthetics is strong.

Kotov traveled to hundreds of Russian cities over three years, and plans to visit more. “Every new place hides its secrets,” he says via email. “It is normal here (in ex-USSR cities) to feel yourself like an archaeologist, who came to the ruins of great ancient civilization, and didn’t know what you would find!”

The photographer spoke with Atlas Obscura about his enthusiasm for Soviet history, fascination with rockets, and nighttime adventures. His book will be published in 2020 by FUEL Design & Publishing.

What inspired you to photograph Soviet architecture?

I got my first camera when I was 22 and had just finished university. It was interesting for me to try out different genres, and more than anything I liked city landscapes. So every evening I went to different corners of my hometown to take pictures from different high-rise residential blocks. Around 70 percent of Samara (my hometown) was built during the Soviet era. I started to see beauty in their strict plan and strong forms. Then after three years, when I was 25, I decided to travel for some time. I lived in Sochi, St. Petersburg, and hitchhiked across Russia, and went to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine. In every place I saw interesting details, not only in individual buildings, but also in whole city plans. I had the idea to make a collection of the most outstanding buildings and districts.

What makes you want to document this particular style of architecture?

Actually I like the process! More than anything, I enjoy traveling in my homeland, and in Russia and the former Soviet Republics, all of them are somehow similar to what I saw in my hometown before. Nowadays the things that unite these separate countries are slowly but surely being destroyed. Sometimes it is time and severe weather, sometimes crazy revolutions, sometimes indifference of people, privatization, or many other reasons. All this urban environment that is so close to people’s hearts, who grew up in 1980s and 1990s, is disappearing. That’s why I decided to document the traces of Soviet civilization. Soon there will be nothing to document.

Were people surprised to see that you had come to photograph everyday Soviet architecture?

Most people do not recognize Soviet architectural heritage as something noteworthy, because in their childhoods it was more customary to admire ancient Orthodox churches or European cities with palaces, castles, and narrow streets. During my childhood, a few people had just started to recognize Constructivist architecture of the 1930s and the Stalin period as something interesting. And in early 2000s some specialists started to talk about Soviet modernism. Architecture needs time to become recognizable, so now the time has come. I don’t blame people that they don’t know anything about this kind of architecture; in several years they surely will.

You used to work in a rocket factory. Did that influence your work?

I worked for three years at a factory where Soyuz rockets are manufactured. It gave me an understanding of how strong and powerful our industry was before. Most other space factories are already abandoned, rented out, or destroyed. When I started my job as an engineer, the factory was semi-abandoned; there were colossal workshops that were completely empty, with Soviet slogans and posters still on the walls. In the courtyard was a huge red hammer-and-sickle monument with “Glory to Labor” on it. I liked to walk around the factory in my spare time, and I was sad that the great story of my ancestors was in the process of being abandoned and forbidden. I think it inspired my photography somehow.

Your photos have a strong sense of pattern and lighting. How do you achieve these effects?

I try to find interesting structures by satellite maps and understand from which place it will be best to photograph them. For city landscapes, I always try to get higher—usually it is possible to get to the roof or public balcony or even to a hill. I always plan every evening. I know when and where the sunset will be, and I try to choose a position that will avoid backlight from the sun.

What was your most challenging site?

In my childhood, I liked to read books about discoverers who were the first to visit unknown regions and put them on a map. One of them was [Alexei] Fedchenko, who was a Russian officer and explorer. The Fedchenko Glacier in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan is named for him, and is the longest outside of the polar regions. And on this glacier there was a unique construction—a meteorological station. After the collapse of Soviet Union, people abandoned it, but it is still in good condition and all the original interiors were safe there. To get to this station I traveled for seven days. The region is absolutely wild, there are no people there except a small camp of shepherds in one canyon. Visiting this abandoned station was the biggest challenge for me.

Do you have a favorite site from the project?

One of my favorites was the trip to the abandoned part of Baikonur Cosmodrome, the world’s first and largest operational space launch facility. It is located in the desert steppes of Kazakhstan and is secured by Russian police, so the best way to get in there is during the cover of night. About three years ago it was discovered, by one Russian urban explorer, that the last great Soviet space projects, the Buran shuttle and Energia rocket, are hidden and abandoned in gigantic workshops there. So after a 35-kilometer [20-mile] hike through the night, it was a fantastic feeling to arrive and get into the enormous workshops where the future of Soviet space program is buried.

Is there someplace that you haven’t photographed yet that you really want to get to?

I really want to get to Norilsk! It is a northeastern city with more than 100,000 inhabitants that was built for miners who work on largest nickel deposit in the world. Summer is very short and winter is long and harsh there, but the landscapes are fantastic: snowy tundra with an industrial city and no trees.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook