On Streets and Subways in South Korea, Poetry Hides in Plain Sight

You’ll find poems in hostels, restaurants, and even on mountain trails—if you know where to look.

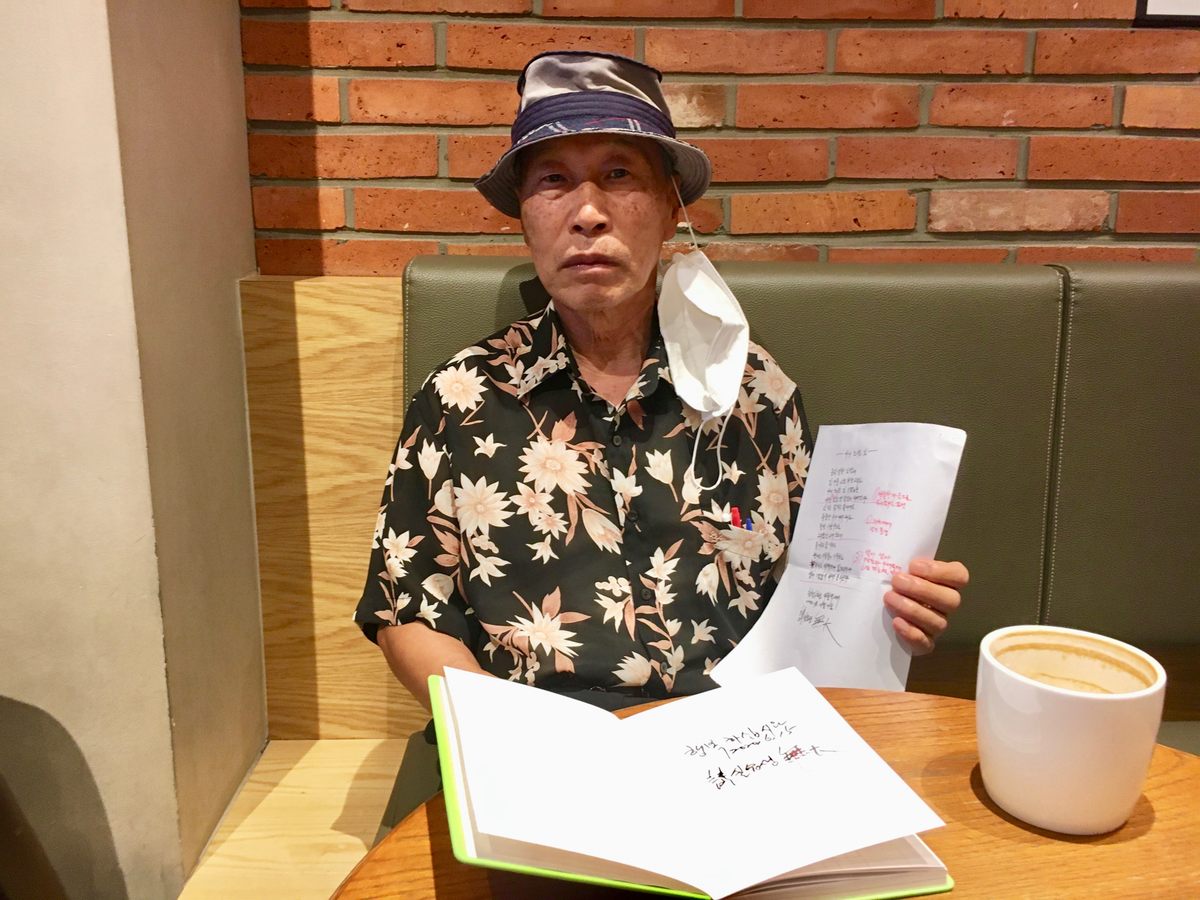

On a foggy July morning in Seoul, 76-year-old Moo-Dae was sitting on a bench in the belly of the Saejeol metro station when he felt the need to write a poem. In the humid summer heat, he was imagining a lonely winter scene: a woman sitting by a flickering candle in the 1970s, waiting for her husband to come home.

“I wanted to write about loneliness,” Moo-Dae recalls a few days later, in his native Korean. His real name is Kim Seung-Yeul, but he prefers to go by a pen name, which roughly translates to “nothing big.” To explain his pseudonym, he says simply, “I have nothing to show off about.”

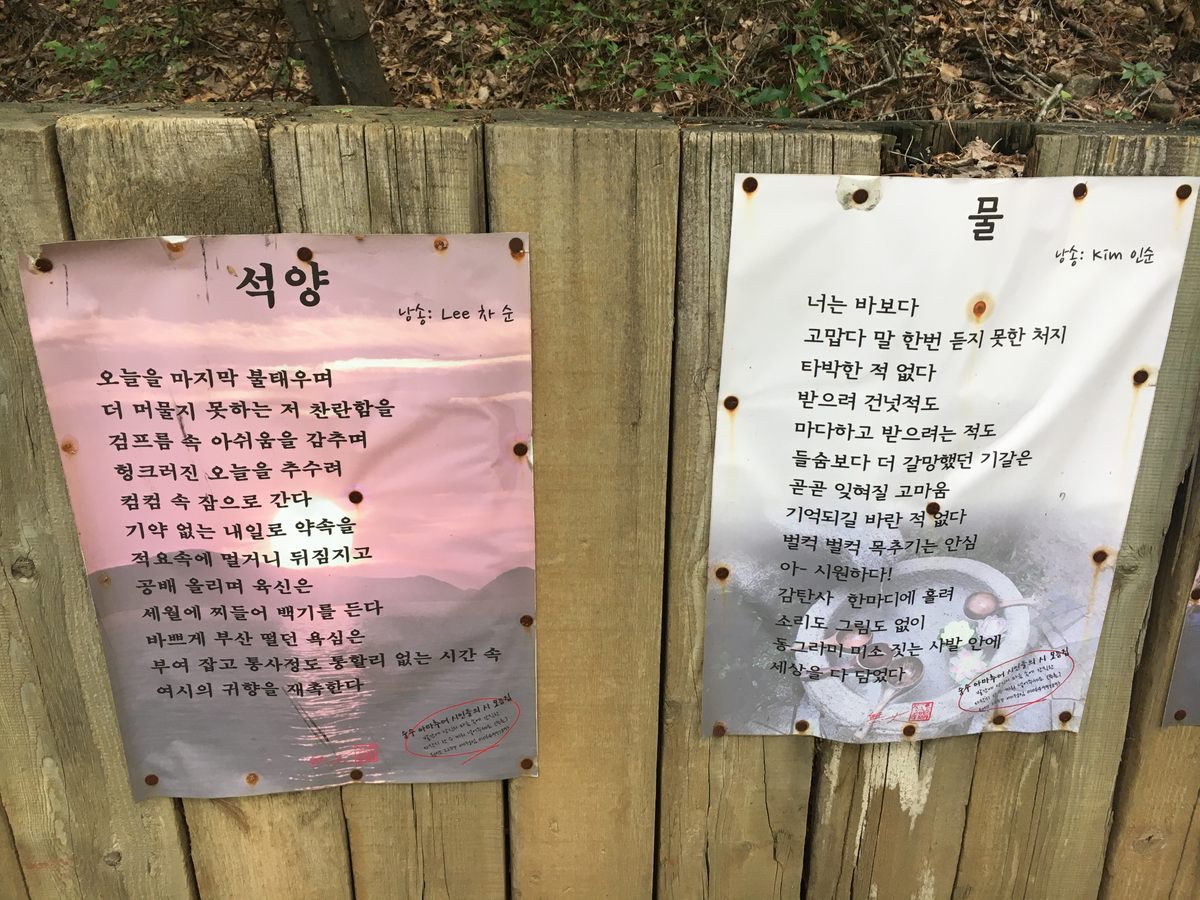

Yet Moo-Dae has left a lasting impression on a handful of public spaces across Seoul. Over the course of 30 years, he has posted dozens of printouts of his poetry on mountain trails and pedestrian walkways. At first glance, the poems—each emblazoned with a red stamp and a label that reads “A Collection Shared by Pure-Hearted Amateur Poets”—may seem like a city initiative or a collaborative art project. But they are all works by Moo-Dae himself, dedicated to friends or acquaintances he wanted to commemorate in some way.

“I wanted to display my poems in public spaces so that people could enjoy them,” says Moo-Dae, who has never formally published any work. “Fame would be sweet, but I don’t think my ability merits any kind of fame. I just want one other person besides myself to read my words.”

A few decades ago, South Korea was a largely agrarian society, but rapid modernization has transformed it into one of the world’s most technologically advanced nations. Still, there’s an olden-day quality to the persistence of poetry in the country’s public spaces. Poems appear in places one least expects: hostel rooms and the windows of restaurants; rest stops on nature walks and amusement-park walkways; urban billboards and even on platform screen doors in the Seoul subway.

“Most Koreans these days are busy people,” says Ham Young-Woo, who works in the Arts & Culture bureau of the Seoul Metropolitan Government. He currently leads a team that, since 2008, has displayed thousands of amateur and professional poems on subway screen doors in over 300 stations. “We wanted to find a way to integrate poetry into their day-to-day lives. Otherwise, I doubt most people would go out of their way to read poetry.”

For centuries, poetry has played an important role in Korean society. In ancient times, the yangban, or Korean nobility, wrote poems not only as part of government examinations, but also to express coded commentaries on their social and political views. (Prospective civil servants still sit for a national exam, but poetry is no longer on the test.) During the 20th-century Japanese occupation of Korea, poets wielded their pens to criticize Japanese imperialism and reclaim their Korean identity as the national culture, language, and history were nearly wiped out.

The Seoul Metro installed glass safety doors in every station in Seoul between 2002 and 2009, to protect passengers from collisions with high-speed trains. In 2008, a literary critic and professor named Kim Jae-Hong suggested that the government reduce the number of advertisements on the doors and fill their spaces with poetry instead. At the time, Kim told Seoul& magazine in 2016, a government agency was emphasizing the importance of poetry for civil servants. “So I suggested that the poems would be good for the development of citizens’ literary sensibilities,” he said.

Amateur poets can submit their work online to an annual government competition, which selects a handful of entries to be printed and posted on the platform screen doors. This year, 3,000 citizens submitted poems to an anonymous panel of judges, who evaluate the works on their literary merit and suitability for public viewing. “The judges try to pick poems that have a healing or soothing quality to them,” Ham says, in part to avoid criticism that the initiative has received in the past. (In 2017, parodies of metro poems went viral on social media after complaints that poorly written or inappropriate amateur poems “ruined public spaces.”)

“There’s no need to consider poetry as exclusive to literary types,” Kim told Seoul&. “If anything, literature needs to remain close to us in our day-to-day lives.”

Moo-Dae, for his part, loves the poems in the metro. “I read them all the time,” he says, beaming. But when asked whether he would consider submitting a poem to the annual competition, he shakes his head. He isn’t very familiar with the internet, he says.

Lee Sang-ok*, 63, believes that digitization is necessary for the survival of poetry. Art has always evolved to fit its era, he says. Hyangga, Korean poems written in Chinese characters through the hyangchal system, flourished in the ancient kingdoms of Silla and Goryeo between the seventh and 10th centuries. Gayo folk songs thrived in the Goryeo period. Sijo poetry proliferated during the Joseon dynasty, and so on and so forth. “As those eras have passed, so have their respective poetry genres,” Lee explains.

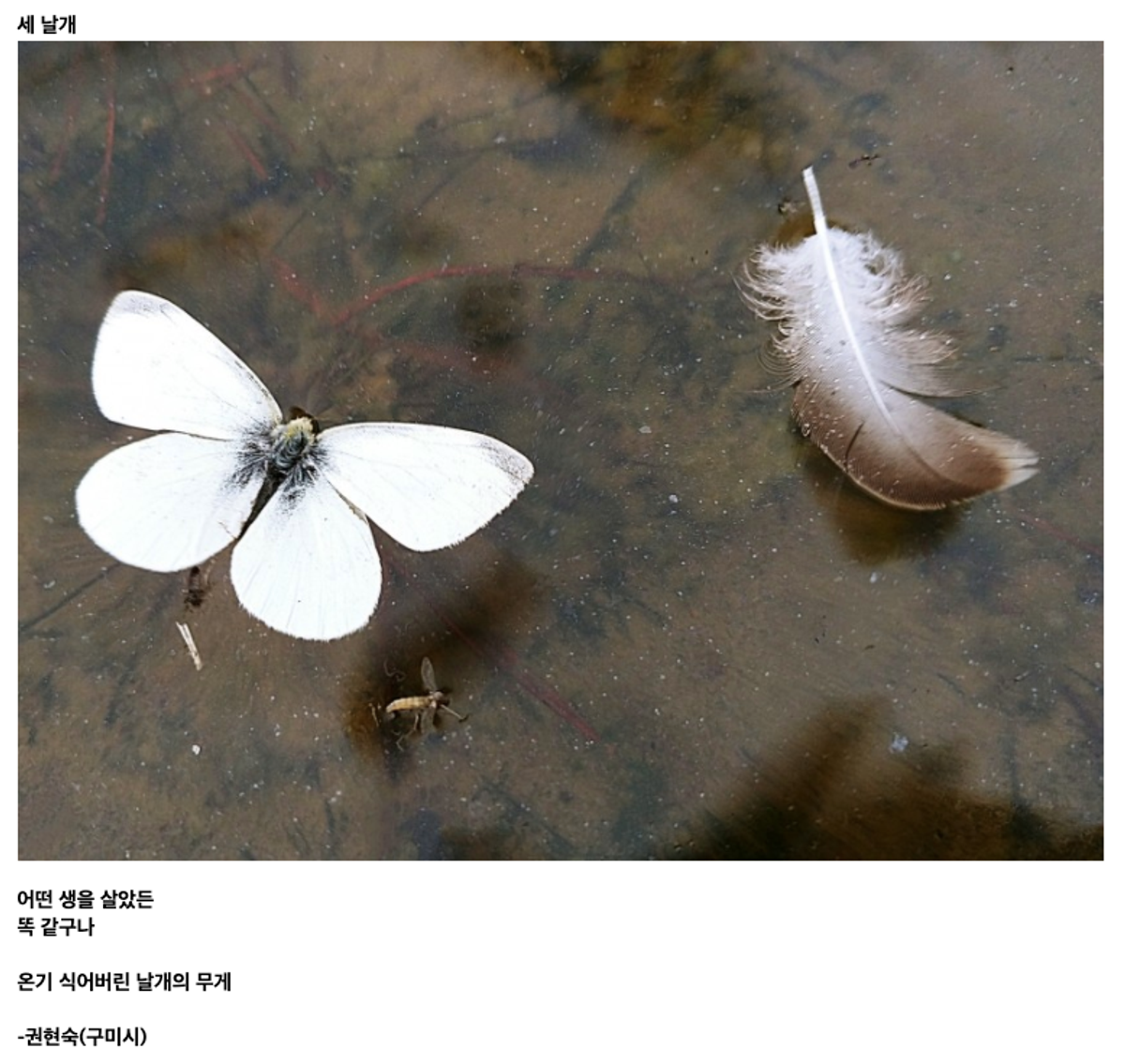

In 2004, Lee invented a new genre named “Dicapoetry” (or “Dica-sshi” when transliterated from Korean), which is a portmanteau of “digital camera” and “poetry.” Dicapoems fuse a photograph and text message-length poem to produce a “multi-genre” piece, which Lee calls “the poetry of the instant.” While coining the term, he imagined that poets would send their work to friends and family instantly after writing it.

Today, Lee runs the Korea Dicapoem Institute from his home province of Gyeongsangnam-do, where he records poetry readings for YouTube at the institute’s bookshelf-lined headquarters. He also oversees the publication of a quarterly magazine, featuring Dicapoems by writers all over the country. “As smartphones ushered in a new media environment, the vision of Dicapoetry was able to become reality,” Lee explains.

One of the dozens of poems on the Dicapoem Institute website is “Three Wings” by the poet Kwon Hyun-Sook. Like all Dicapoems, it begins with a digital image, in this case Kwon’s snapshot of a dead moth, a dead mayfly, and a pigeon’s feather on a frozen lake. The poem reads: “Regardless of the lives they’ve lived / it’s all the same / the weight of wings without their warmth.”

Moo-Dae, the 76-year-old amateur poet, has been planning to expand his project into new public spaces. He wants to display his poetry along the Han River, as well as the common areas of apartment complexes and the hip district of Hongdae, where university students shop for clothes and listen to buskers sing.

But he worries that old age will put a stop to his poetry. “If a young person might be able to take on the idea that I’ve had, perhaps this initiative might be able to continue,” he says. For now, Moo-Dae continues to write and meet with people whose names eventually find their way to the bylines of his poems. He finds kindred spirits in the process, like he did at a naengmyeon noodle restaurant beside a bridge where he has displayed some of his work. Their noodles are delicious, he says. What’s more, he adds, “the walls of the restaurant are covered in poems.”

* Correction: A previous version of this article mistakenly identified Lee Sang-ok as Lee Sang-soo.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook