Remembering a Little-Known Chapter in the Famed Endurance Expedition to Antarctica

The epic survival story of Ernest Shackleton and his crew included a harrowing journey to Elephant Island.

Excerpted and adapted with permission from Ranulph Fienne’s Shackleton: The Biography, published January 2022 by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2022.

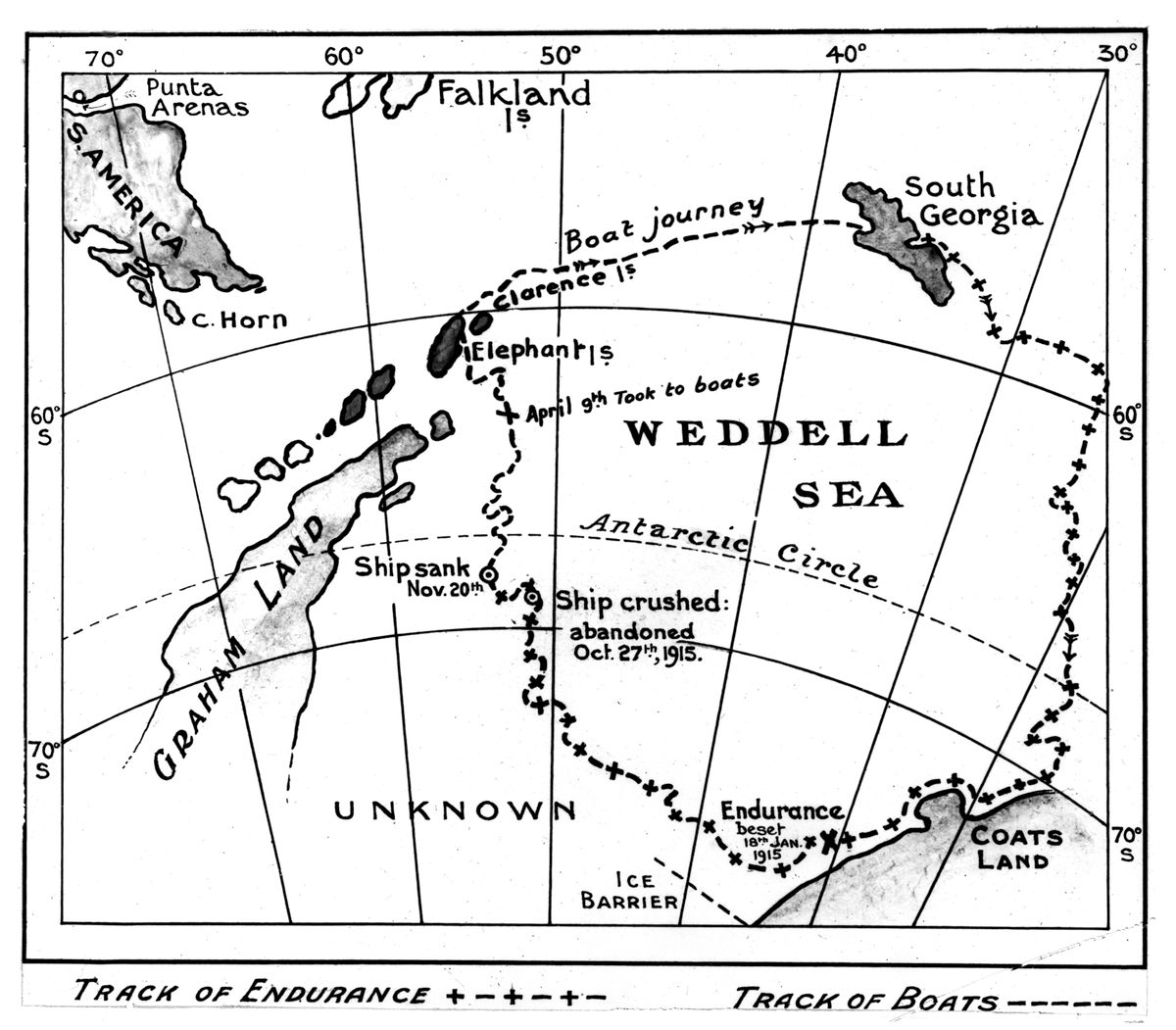

When explorer Ernest Shackleton and his crew set out for Antarctica on the Endurance in 1914, they had no idea their journey would become one of history’s greatest epics of survival. After sea ice trapped the ship for nearly a year, ultimately crushing it, the men camped on unstable sea ice for months. The loss of the Endurance and a later, extraordinary ocean crossing to South Georgia Island by a small party led by Shackleton are well-known chapters in the saga. Less familiar is the story of what happened in between those two events, when Shackleton decided the crew would leave their position on the ice and venture in small open boats across the infamously rough Southern Ocean, to one of the region’s uninhabited islands.

In the unrelenting darkness of the Antarctic winter, the conditions were even worse than they might have imagined. The sea churned with huge ice chunks, forever crashing together, with the men fearing they would be squashed between them. Unprotected, they were battered by the chilling winds, freezing sleet, and fog, and sprayed relentlessly by the ice-cold sea. The threat of killer whales thrusting through the water and capsizing a boat was also ever-present.

The possibility of crossing the 200 miles to King George Island soon looked extremely unlikely. Shackleton realized that their best bet was instead to aim for Clarence or Elephant Island, just 60 miles away. They were, however, at the mercy of the wind. If its direction was unkind, even if they rowed with all their might in the opposite direction, they could be blown into the open water, with no other dry land for hundreds of miles. Still, it was the only choice they had.

After an arduous day rowing, the men found they still could not rest. That first night, they hauled the boats onto a giant passing floe, hoping to set up a temporary camp and get some sleep. However, as the men slept, Shackleton was checking in with the night watchman when, directly beneath one of the tents, the floe cracked in two. Screaming for the men to get out before they plummeted into the ocean, he raced to the tent, only to find sailor Ernie Holness thrashing around in the water, still in his sleeping bag. Grasping the bag with his fingertips, Shackleton gritted his teeth, and using all his might hauled Holness to safety.

When dawn eventually broke, they wasted no time hurrying off the remnants of the floe and onto the boats. Soon after, it appeared they had met with some good fortune. The pack ice had disappeared altogether and they were finally out into the open sea. For so long they had prayed for this, but it was to prove a false blessing. Without the ice they were now pounded by great, rolling, breaking waves. With the heavily laden boats sitting low in the water, there was real concern that they might be overwhelmed and sink. It would be nothing less than suicide to continue, so Shackleton ordered the boats to return to the ice and set up camp, in the hope that the exhausted men would get some rest while Shackleton refined his strategy.

Again, there was to be no respite. The fierce winds drove the floe further back into the pack, and the risk of them being smashed by the enormous passing bergs made it impossible to launch the boats. All they could do was wait for a safe path to open up when the pack opened further. They were truly between the devil and the deep blue sea.

As the ice disintegrated all around them, Shackleton ordered the men onto the boats. From now on, there would be no stopping for camp until they made it to dry land. They just had to hope the boats didn’t sink in the ferocious swells.

The men now rowed even harder, not wanting to spend any longer in the water than was absolutely necessary. Yet dwindling rations meant that this extra exertion could not be compensated for, and some of the men almost passed out. Hot milk was regularly provided to keep them going, but it was not enough.

That night, the men slept in their boats, in the shadow of a giant iceberg, which at least provided some shelter from the bitter wind. Having no cover, and in soaking clothes, they huddled together for warmth. Hypothermia was just a whisker away.

On April 12, 1916, Endurance captain Frank Worsley, catching sight of the sun, positioned his sextant to work out their position. It was not good. Despite all their hard work with their oars, the currents had left them no closer to the islands than when they had first set off, still 60 miles away from the nearest land.

That night was one of the worst they had faced on the ocean. The already freezing men were battered by barrage after barrage of water pouring into the boats. By the morning, they were covered in a film of frost, with thick ice hanging off their beards. Their clothes were so frozen that Frank Wild, Shackleton’s second in command, described them as like ‘wearing a coat of armor’. Meanwhile, thick layers of ice rendered the oars too slippery to handle. Many of the men’s frost-damaged fingers struggled to grip them in any event.

Facing another day of rowing in the cold ocean, unsure if they were making any progress, a sense of hopelessness descended. Shackleton, who, up until now, had been setting an example, was becoming a little frayed. His booming voice failed him and he could now only hoarsely whisper orders.

Just as things seemed to be descending into chaos and hopelessness, there came some hope. On April 14th, Clarence and Elephant islands came into view. Although still 40 miles away, this was the closest they had come: an encouraging sign that they were at last making headway. Shackleton tried to cheer everyone up by shouting to navigator Worsley that they should reach their island goal the following day. But Worsley dismissed the prospects, feeling it would take far longer. Shackleton was silently furious with him. He had only said as much to help boost morale. And soon after, morale was to take another shattering blow.

That night, Wild said the conditions were ‘The worst I have ever known.’ In temperatures of minus 20 degrees, a thunderous storm tossed the boats like toys on the sea and the swirling gale hurled wave upon wave of freezing water onto the men. Such was the force of the wind, the Dudley Docker was separated from the other boats and carried off into the darkness. It appeared all on board were lost.

The next day, mourning the loss of those on the Dudley Docker, the men were unable to muster much enthusiasm when the cliffs of Elephant Island came into view. Yet this was no time to mourn. A narrow beach on the island’s eastern cape had been spotted, and all the surviving men needed their wits about them if they were to make landfall safely.

Approaching land, Shackleton suddenly caught sight of the Dudley Docker heading their way. All the men were safe, if battered and wet. They had survived the storm and found their way to the island at the very moment Shackleton and his men were set to land. It was the best news Shackleton had received in quite some time.

Soon after, the boats were brought ashore, and the men put their feet on solid land for the first time since December 5, 1914. Some frantically slaked their thirst with stream water, others staggered about like zombies, or manically laughed to themselves. The expedition’s magnetician Reginald James wrote, ‘We did not know, until it was released, what a strain the last few days had been.’

The island was nothing more than a speck of rock in the cavernous ocean, but it was the safest haven they had been in for over a year. For now, Shackleton could rejoice at what he had achieved, but he knew this solution could only be temporary. Unless they were spotted by a passing whaler—rare in these waters anyway, let alone out of season—they would at some point have to undertake another journey to reach civilization.

There was to be no immediate rest for Shackleton. The shore where they had landed was just 100 feet wide and the cliff face behind was stained in water marks. It was a death trap. If they camped there, they would be swamped by the tide.

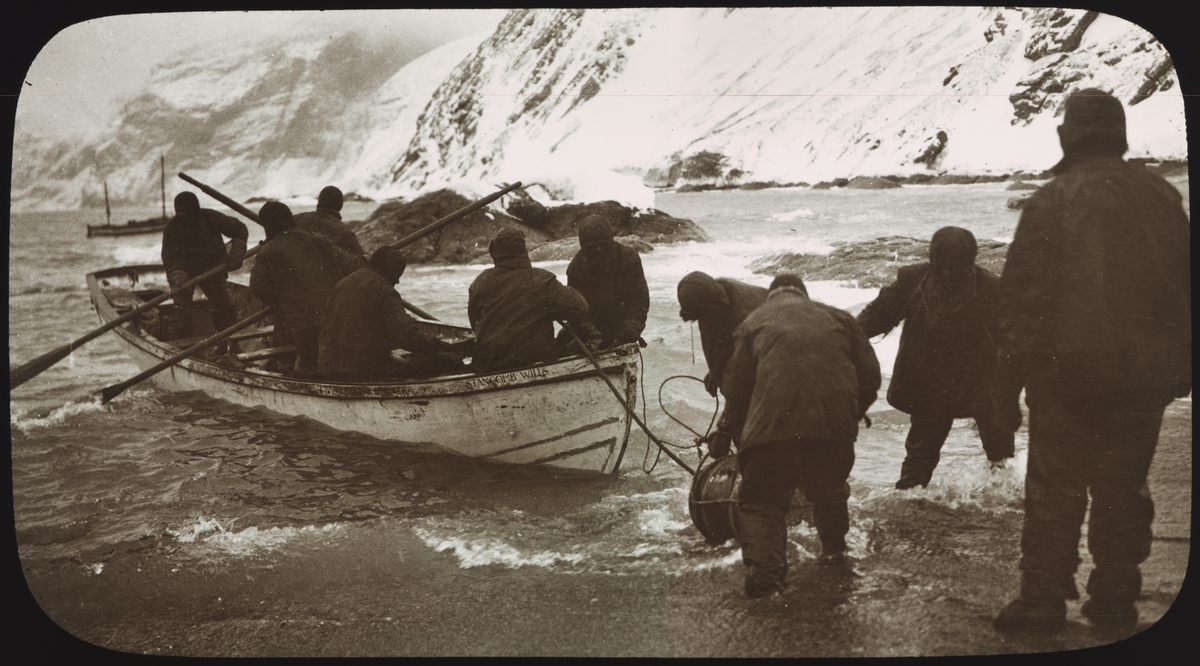

No alternative campsite could be found in the close vicinity, so Shackleton sent Wild and a small party on a scouting mission. Boarding the Stancomb-Wills, they sailed seven miles along the coast and soon found what Wild referred to as ‘paradise’. This might have been stretching things, but at the very least he had found what appeared to be a safe spit of land. Just 100 yards long and 40 yards wide, it backed on to a 1,000-foot cliff and appeared to offer a ready supply of seals and penguins to hunt, with fresh water available from nearby glaciers. In the circumstances, it was all they could have asked for.

However, getting everyone to their new home, christened Cape Wild, was not so easy. While it was just seven miles away, the boats now faced a fierce wind which threatened to blow them further out to sea. For over six hours the exhausted men once more toiled, rowing furiously against the wind, determined not to lose their chance when they were so close. The effort took its toll. When they arrived, in darkness, Lewis Rickinson, the chief engineer, suffered a heart attack. Luckily, he survived.

The boats were quickly unloaded, and they then built a shelter with rocks as walls and the upside-down Dudley Docker and Stancomb-Wills utilized as a roof, while tent materials were used to keep out the bitter winds and snow. The 28 men were soon packed inside, desperate for warmth, and sleep, at long last.

Early the next morning they were awoken by hurricane-force winds. Tents were ripped from the ground, and personal possessions blown into the sea, including clothes and cooking pans. When trying to retrieve them, the men were almost blown off their feet.

They would not last long in such conditions. But the nearest habitable landfalls were Port Stanley on the Falklands and Cape Horn at the tip of South America, both around 600 miles away. Elephant Island was not on any known shipping routes and there was no way they could signal for help.

Some of the men gave up hope. They had already been through so much, and now this appeared to be as good as it was going to get. Many believed they would die on the island and struggled to find the motivation to rise from their sleeping bags in the morning. Soon, a general sense of despair swept through the camp.

Shackleton knew that, without any plan, some of the men would spiral into a dark depression and some would go totally mad, thus, he said, ‘the conclusion was forced upon me’. He realized that the best course of action would be for him and a small party to lead a rescue mission while the others stayed on the island. However, he was well aware that their small boat would not survive the strong winds and currents to the Falklands or Cape Horn.

Consulting the map, he decided that their best chance of success was to return to South Georgia, from where the Endurance had first set out. This might have been over 800 miles away, but they would have the advantage of the westerly wind, rather than having to fight against it. There was, however, one distinct disadvantage. Such were the size and strength of the monster waves in this area, whaling skippers had christened it the ‘great graveyard’. No small boat was known to have survived in its waters. Even the ever-optimistic Shackleton understood the odds would be against them, writing, ‘The perils of the journey were extreme.’ But if he was to make such an attempt, there wasn’t a second to lose. By May, the pack ice would have closed off all available routes and they would face spending winter on the island. Indeed, Shackleton could already see pack ice on the horizon, creeping closer every day.

A brief spell of hope swept across the camp as Shackleton made his final preparations. No matter that he had spelled out the dangers of the journey to everyone, and the slim likelihood of success, most still put their faith in the Boss. So far, he had not put them wrong and had displayed quite incredible powers of recovery and survival. If there was anyone on earth they wanted for such a mission, it was Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook