Antarctic Explorers Wrote Cute, Funny Stories to Hide Dangerous Stunts

Eventually, even imagined mushroom fantasy lands could no longer mask the perils.

The sun hadn’t been seen above the horizon in months and wouldn’t return for another few weeks. Griffith Taylor, a geologist on Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition, had little to do. He scanned a years-old issue of a magazine from back home in England, his bored eye catching on a ladies’ fashion column detailing the new styles of the day. After a moment, he looked up to see his bunkmate, fellow geologist Frank Debenham, working on his rock samples. The proverbial lightbulb went off above his head.

If his hirsute bunkmate were instead a stylish and editorial lady, what sort of column might she write about the latest Antarctic fashions? Taylor began to scribble down his affectionate parody, casting other members of the expedition in roles as fashionable women or shop owners as well.

This article was no private project, hidden under a mattress: It appeared fully illustrated in the next issue of the expedition magazine, the South Polar Times and was read out loud by Captain Scott at the dinner table. This was just the beginning of a long Antarctic tradition of passing the winter by publishing fantastical stories, often via parody, poems, and strange nonfiction. By poking fun at their harsh conditions, early Antarctic explorers used funny and sometimes oddball storytelling to deal with the difficulties they faced. Over the years, however, the bizarre stories revealed more and more harrowing perils of the expeditions.

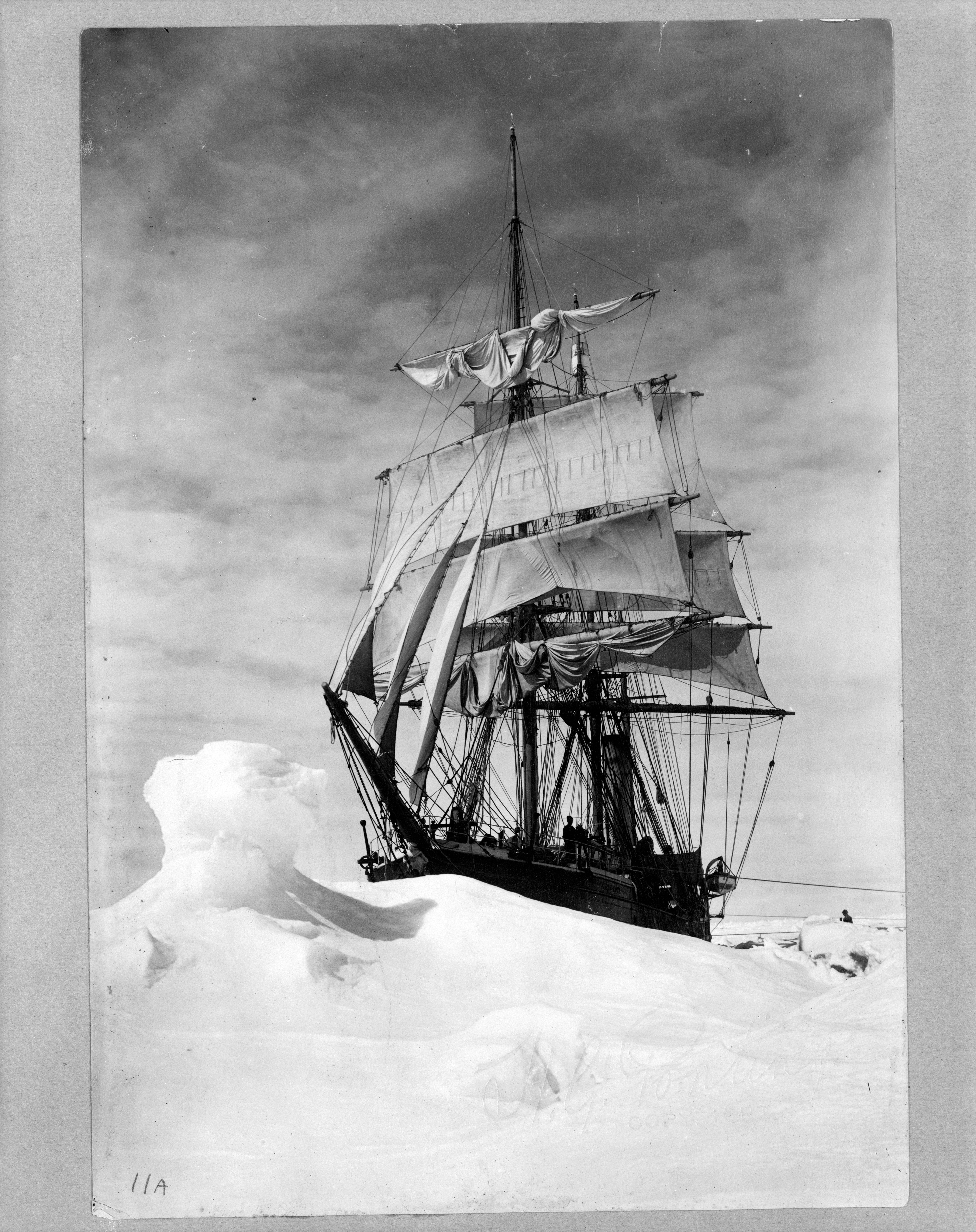

On-ship entertainment wasn’t exactly unprecedented. Sailors had a long history of creating amusement onboard, like plays and masquerades, but publishing was a new feature specific to polar expeditions. The first South Pole expeditions actually took inspiration from journeys in the North, where winter also lasts months. Explorers deep in the Arctic Circle faced cold and darkness, and had to “winter over,” hunkering down in their ships trapped in the polar ice pack—and therefore with more free time on their hands.

During one winter in 1819, a Northwest Passage expedition created a handwritten newspaper called The North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle to amuse themselves while waiting for the sun to return. They passed it around the ship, and later typed it up as a memento when the expedition returned home.

A couple decades later, printing presses were put onto ships during the search for the lost Franklin expedition to the Arctic. Crews used the machines to print leaflets and distribute flyers to help find the missing sailors. Several ships kept these presses and used them during the winter to produce the first printed polar periodicals.

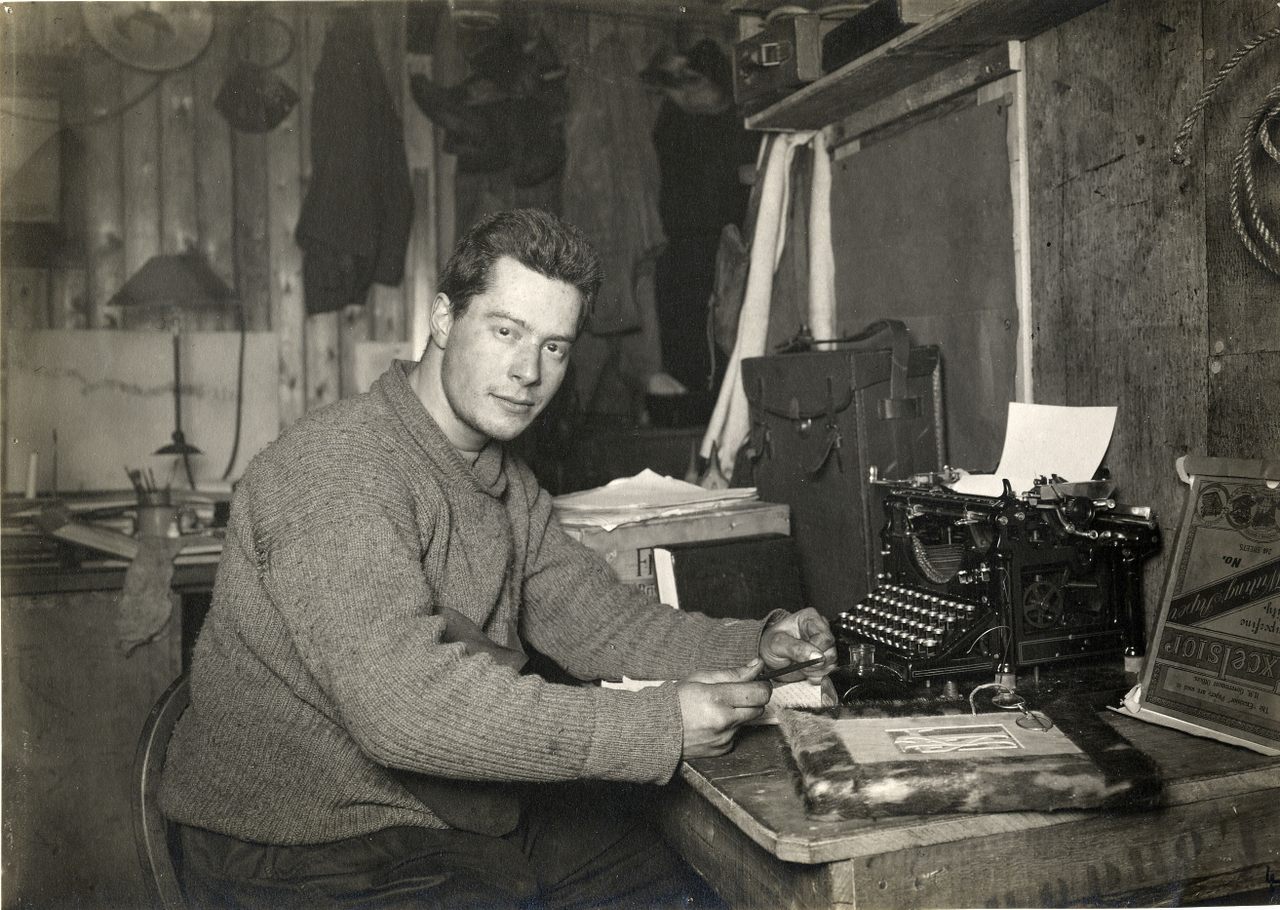

Explorers in Antarctica took the idea and ran with it. In 1902, members aboard the ship Discovery led by Captain Scott created a publication called the South Polar Times. After asking for submissions from everyone on board, from the lower deck workers to the officers and even the captain, the young lieutenant Ernest Shackleton typed everything on a typewriter, and the junior surgeon and naturalist Edward Wilson illustrated it by hand. Full of scientific observations, puzzles, caricatures, poetry, and reports on shipboard games, each new issue was anticipated by all the men.

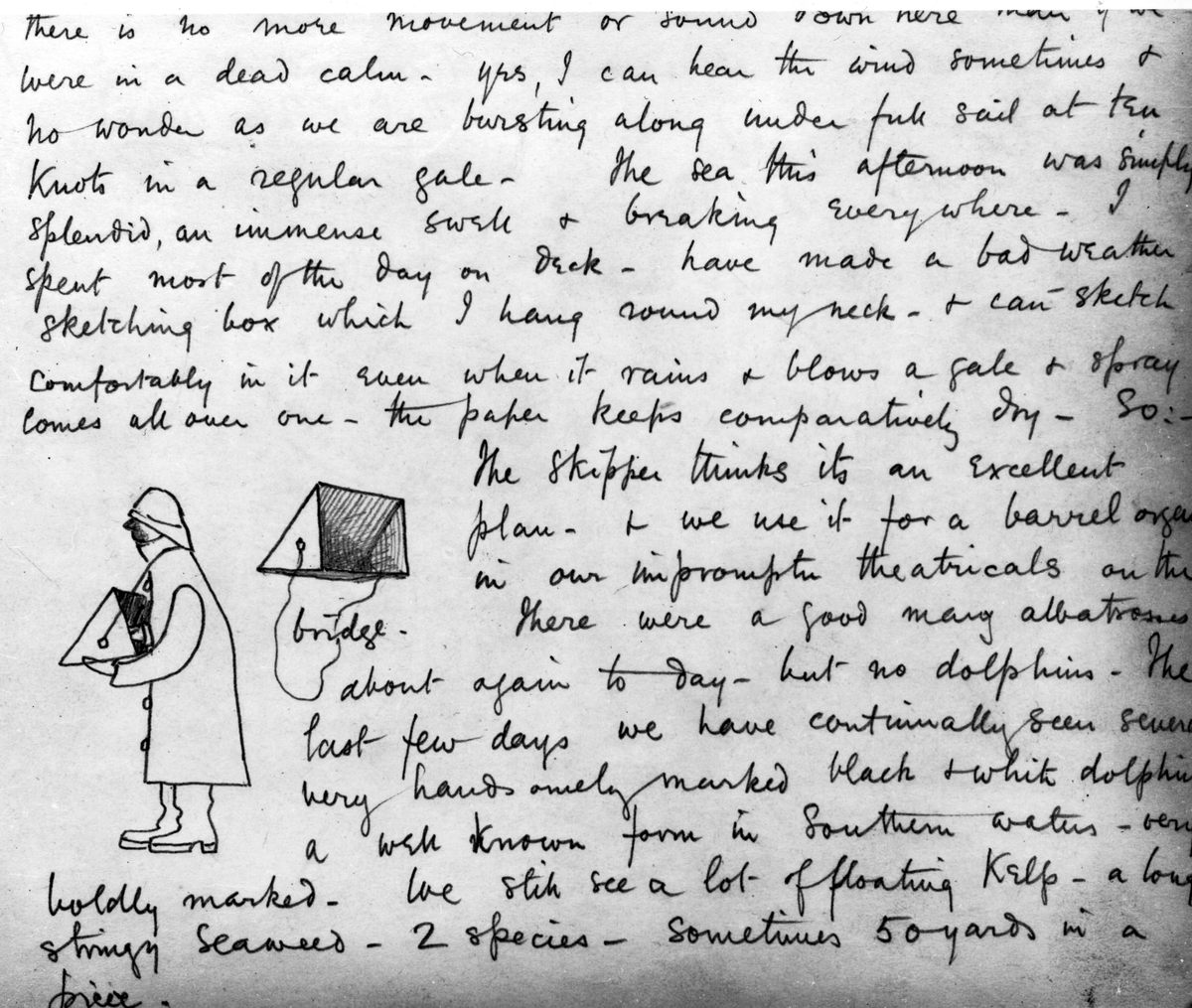

Many of the stories spoke to the struggles explorers faced. Captain Scott wrote facetiously of the trials of camping on the ice. He described paraffin fuel getting into all the food, the struggle of leaving their sleeping bags when it was 40 degrees below freezing, and the hour it took to put on leather boots that froze solid overnight, along with the copious sailor cursing produced by this inconvenience.

“Someone is frustrated with somebody else, and they can voice that within the funny or literary framework of whatever they’re doing, in a way that they just can’t do directly,” says Elizabeth Leane, professor of Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania.

Penguins featured heavily: This expedition was one of the very first to spend time among the Emperors and Adelies, and they were sources of endless fascination to the men. There was doggerel about the strange, foreign taste of the penguins they had for dinner, as one described when writing, “‘Twas like shoe leather steeped in turpentine / But I should hardly like to call it ‘Flesh’”.

The perils of the Antarctic were generally minimized and mocked by the stiff-upper-lipped explorers, without acknowledging failures—but still, some allusions to the real terrors they faced slipped in.

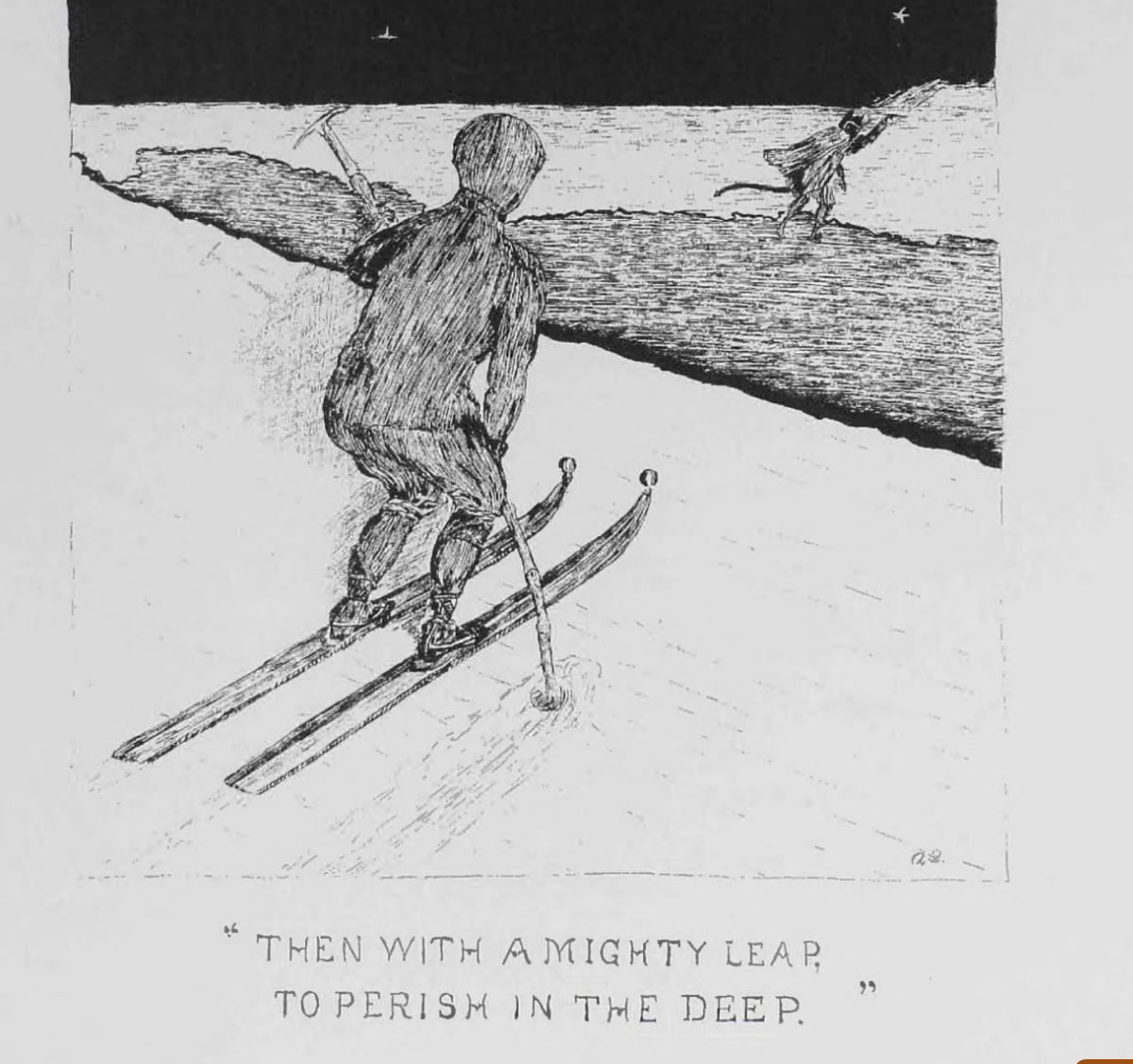

A poem by stoker Arthur Quartley depicts a deal with the devil made by a skier who plunges off an icy cliff to his death—and then wakes from his nightmare in his bed. It’s thought to have been inspired by the death of his friend George Vince, a sailor who fell to his death off an ice cliff while attempting to get back to base during a blizzard.

This expedition failed to make it to the South Pole, but more attempts—and strange stories—were about to come.

“Since most expeditions are not successful, the only thing that comes out of them is writing,” says Hester Blum, author of News at the End of the Earth. “The South Polar Times becomes… a way of showing the creative, cultural effects of that community.”

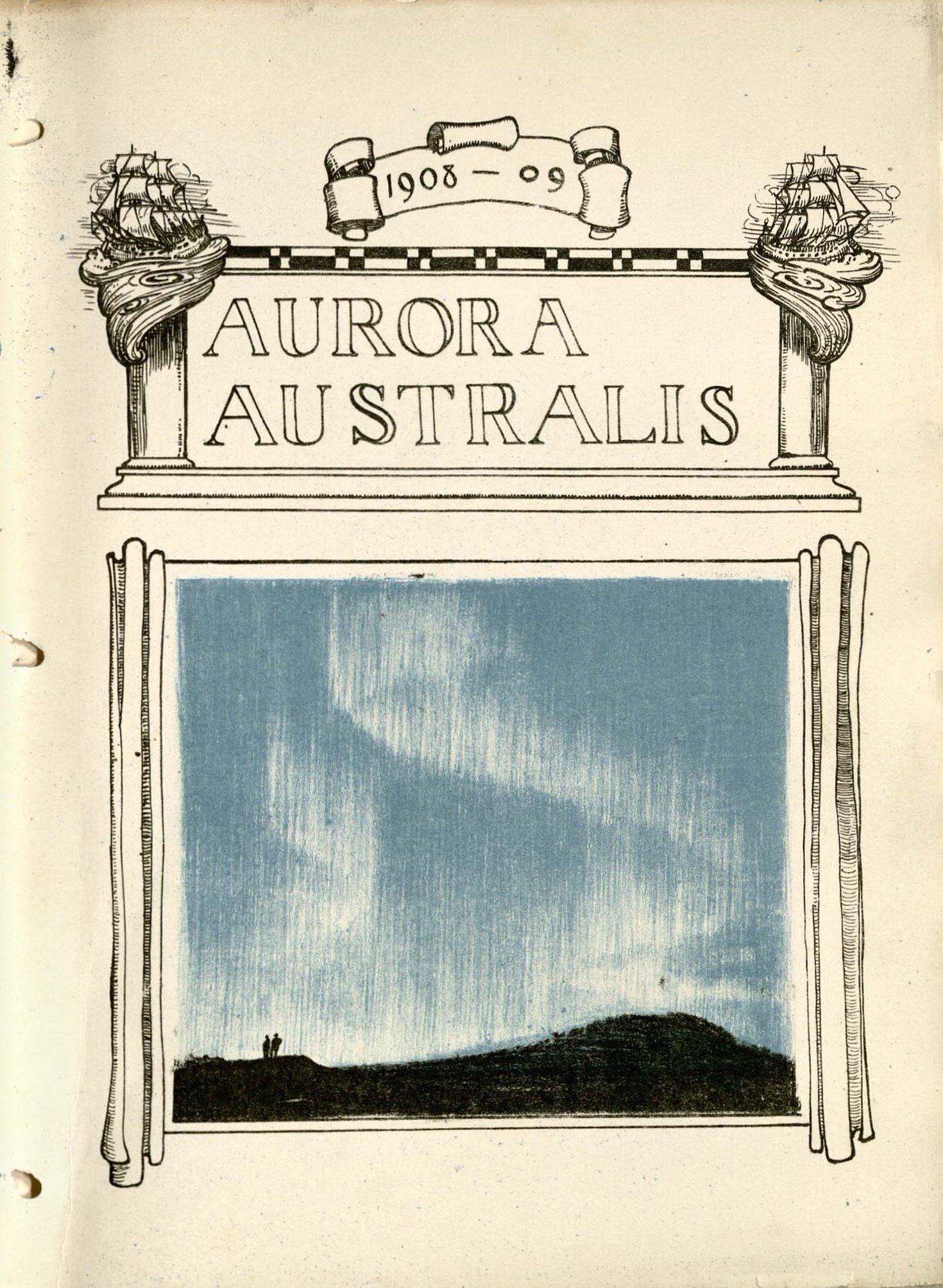

The next expedition to Antarctica took publishing a step further. After failing to reach the South Pole with Scott, Shackleton decided to have another go. He sailed back to Antarctica on the Nimrod in 1907, determined to be the first to the Pole—and also to produce the first-ever book printed in Antarctica: Aurora Australis.

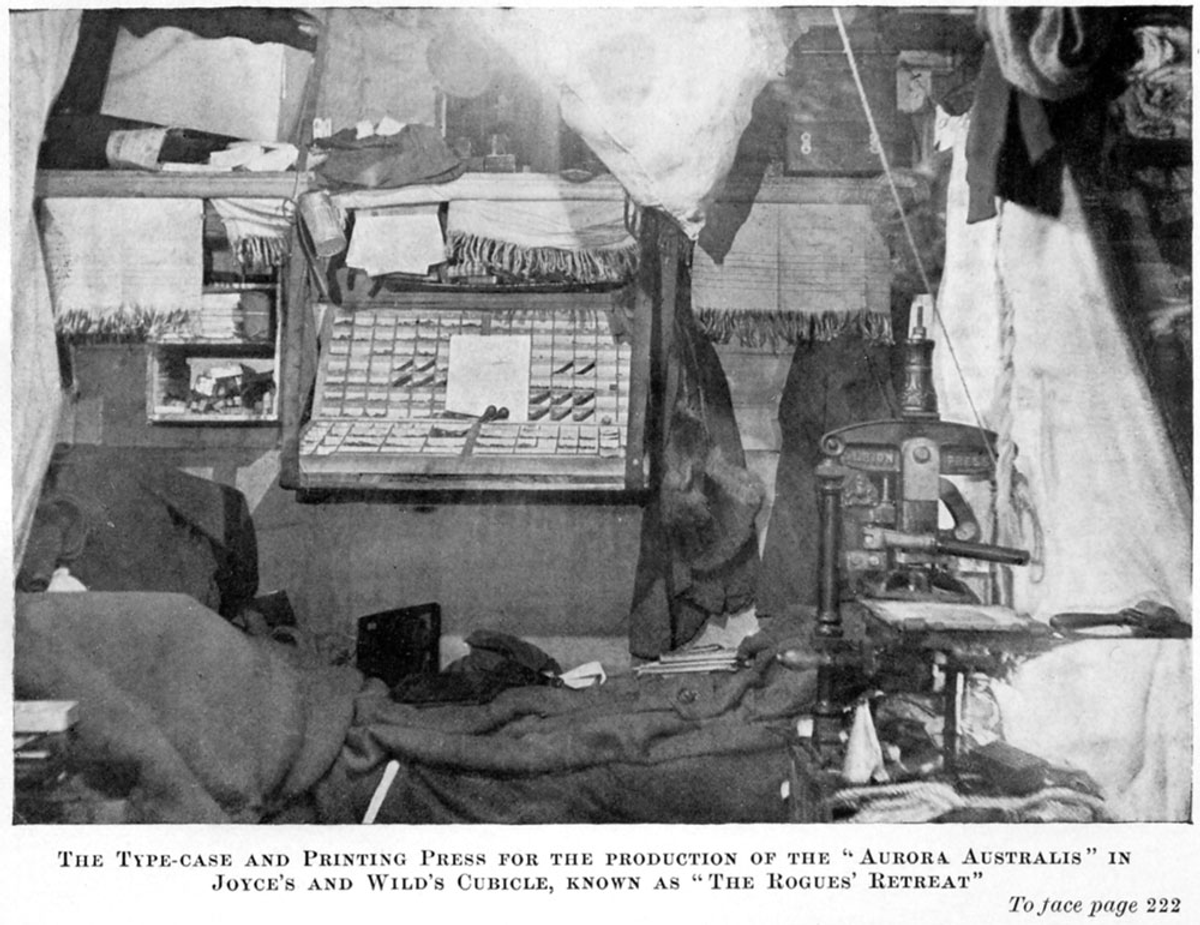

As part of his preparations for the expedition, he secured a loan of a printing press. He also sent two of his men on a three-week printing crash course before setting sail.

It was much more challenging to produce a printed book during polar winter than a typed magazine. The temperature in the hut was so cold, the ink froze. One solution was to light a candle underneath the printing plate—but then the ink became too slippery and fluid. Eventually, someone had to manually move the candle around to keep the temperature even.

When it came time to bind the books, without the proper materials, the expedition’s crafty engineer made use of the plentiful supply crates scattered around the hut. He used wooden panels as covers, sewed the spines with the same thread used to repair tents, bound it in leather recycled from harnesses from ponies that had perished in the cold, and then polished the plywood covers to perfection. In libraries and private collections around the world today, copies of the Aurora Australis are still covered in large print letters reading “TURTLE SOUP,” “MUSTARD,” “LIQUID BOTTLED FRUIT,” and “BEANS.”

Because of limited supplies, Shackleton had to be more selective about contents than he had been with the South Polar Times.

One piece published was about the mandatory task of serving as the cook’s assistant, or messman. Before the expedition, scientist Raymond Priestley didn’t even know what a messman was, but he soon learned. Keeping an Antarctic expedition fed was incredibly labor intensive. The messman had to go out into the freezing cold to gather ice to melt for water and bags of coal for the fire. He had to spend hours removing stones from raisins, a much more difficult task than he imagined. “To a man of my refined and sensitive nature, it is singularly repulsive to be beaten by a fruit,” Priestley wrote.

Another piece was a science-fiction story about exploring an undiscovered tropical region of Antarctica. It imagines the Nimrod’s party making their way into the strange land of Bathybia, 22,000 feet below sea level. They used rafts made of giant, man-sized mushrooms to travel down rivers into a red jungle, encountering giant ticks, alcoholic algae, and huge carnivorous versions of microscopic Antarctic rotifers.

Blum thinks this story might have been inspired by Jules Verne and Edgar Allan Poe. “The vision of this hypertrophic region is so consistent with that kind of fiction,” she says. “It’s just a really cool way of imagining deep time.”

Shackleton also failed to make it to the South Pole, so one more expedition launched with another set of published wonders. Scott decided to try the attempt again, this time aboard the Terra Nova in 1910. The South Polar Times was therefore revived, this time getting darker as the expedition became more dangerous.

The publication started off casually, such as a parodic poem called “The Sleeping Bag,” which concludes:

If you decide to side with this side, turn the outside furside inside;

Then the hard side, cold side, skinside, beyond all question’s inside outside....

AND it does not matter a particle what you do with the bally thing, someone’s sure to tell you it’s outside inside.

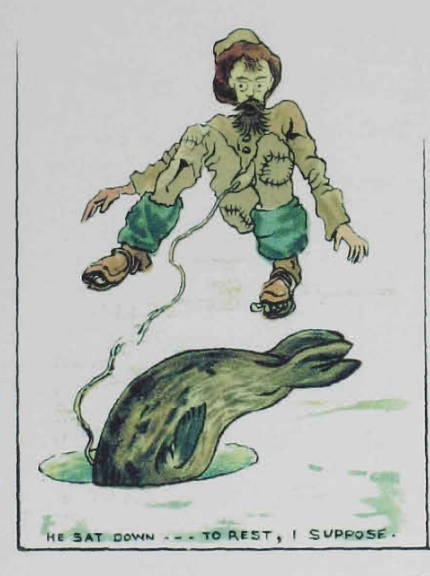

Then more hazards start to enter plots. T. Griffith Taylor’s flirtatious letters between a seal and a skua gull hint at a real-life event.

The seal, “Miss Celia Weddell,” humorously describes an incident that had actually occurred when Taylor was visiting the Ferrar Glacier earlier in the year. He had lassoed a seal with the rope of his sledge harness. The seal then lolloped rapidly back towards her hole in the ice, pulling the man along with her. Taylor nearly went down, but was able to remove the lasso just in time, barely saving himself from certain death.

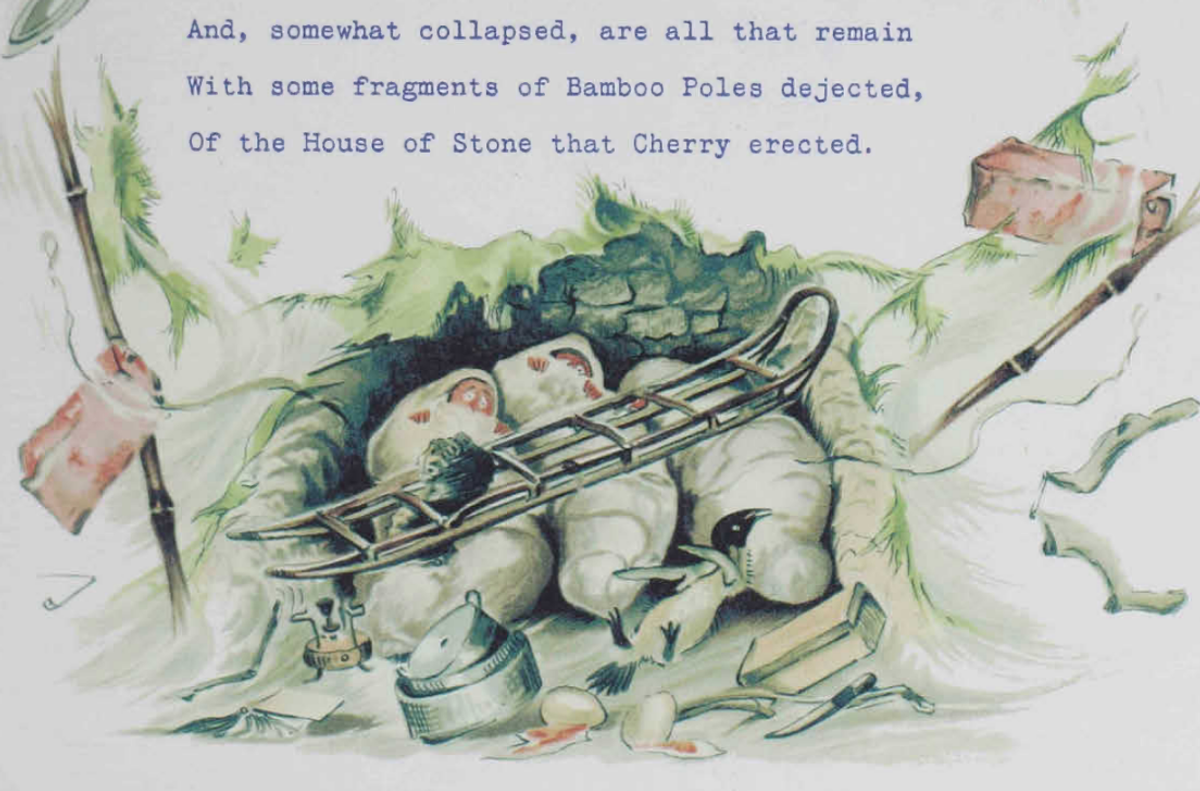

Another story similarly makes light of one of the most dangerous incidents of the expedition. A poem called “The House That Cherry Built,” is an overly cheerful account of three men who took shelter after their tent blew away. In actuality, the story references the time a blizzard carried off the three men’s tent during a trip to Cape Crozier, and they nearly died in temperatures of minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

Finally, the expedition got to a point in 1912 when even the toughest sailors could no longer make light of the dangers. A party led by Scott had failed to return from the South Pole. In the next edition of the South Polar Times, any references to members of Scott’s party were censored, in accordance with the group’s agreement to avoid any mention of their dead friends for the entire winter. When the magazine was published upon their return home, the somber 1912 issue was not included.

Afterwards, polar publishing was never quite the same. The main reason has to do with the invention of radio. An Australian expedition in 1913 managed to successfully transmit radio to Antarctica. Much like the Terra Nova men, their party had been reduced by tragic deaths on the ice. But the remaining seven men included a wireless operator who managed to get the antenna to work, finally connecting them to the outside world. This had a big impact on the contents of their paper, the Adelie Blizzard.

“They make a big fuss about it at the start,” Leane says of the Blizzard. “They say this is the first real Antarctic newspaper, because it’s the first one to actually print news of the day.” With the ability to get updates directly to and from civilization, published stories became less insular. Expeditions began to revolve around sending radio updates to the global public. “The idea of the newspaper, and what is the news—not that there was ever any real news, other than the inner life of the expedition—just becomes different,” says Blum.

A few other publications sprang up over the years, like The Hallett Daily Hangover and The Casey Rag, at new permanent stations in Antarctica. The Antarctic Sun was the last major publication seen in Antarctica, which began in 1957 as the McMurdo News, became censored by the Navy in the 1970s due to its anti-Vietnam War stance, switched from paper to digital in 2007, and has gone quiet in 2023 with no one to take previous editor Lauren Lipuma’s place.

Today, you’re more likely to find social media posts as the biggest news coming out of Antarctica. Still, throughout the years and to this day, amid the general daily news and scientific reports, you can still find a strong satirical edge, full of lampoons about station life and plenty of in-jokes. But these days, expeditions are decidedly more connected to the outside world and more safe on their journeys. And at least there’s no more eating penguins.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook