Along the Remains of Route 66, Road Trip Trash Has Become Treasure

Welcome to the “throw zone.”

As America’s highway system sprawled in the middle of the 20th century, families began to spend vacations on the road. Route 66, also known as the “Main Street of America” or the “Mother Road,” was one of the country’s major asphalt arteries. Beginning in the 1920s, it took drivers west and back—more than 2,000 miles from Chicago to Los Angeles. Parents folded and unfolded maps, while the kids saw Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona blur past from the backseat.

Though Route 66 was more or less out of commission by the mid-1980s, you can visit portions of its old path—and, if you look closely, you’ll still find evidence of the drivers and passengers of decades past, in the form of the garbage they chucked out their windows.

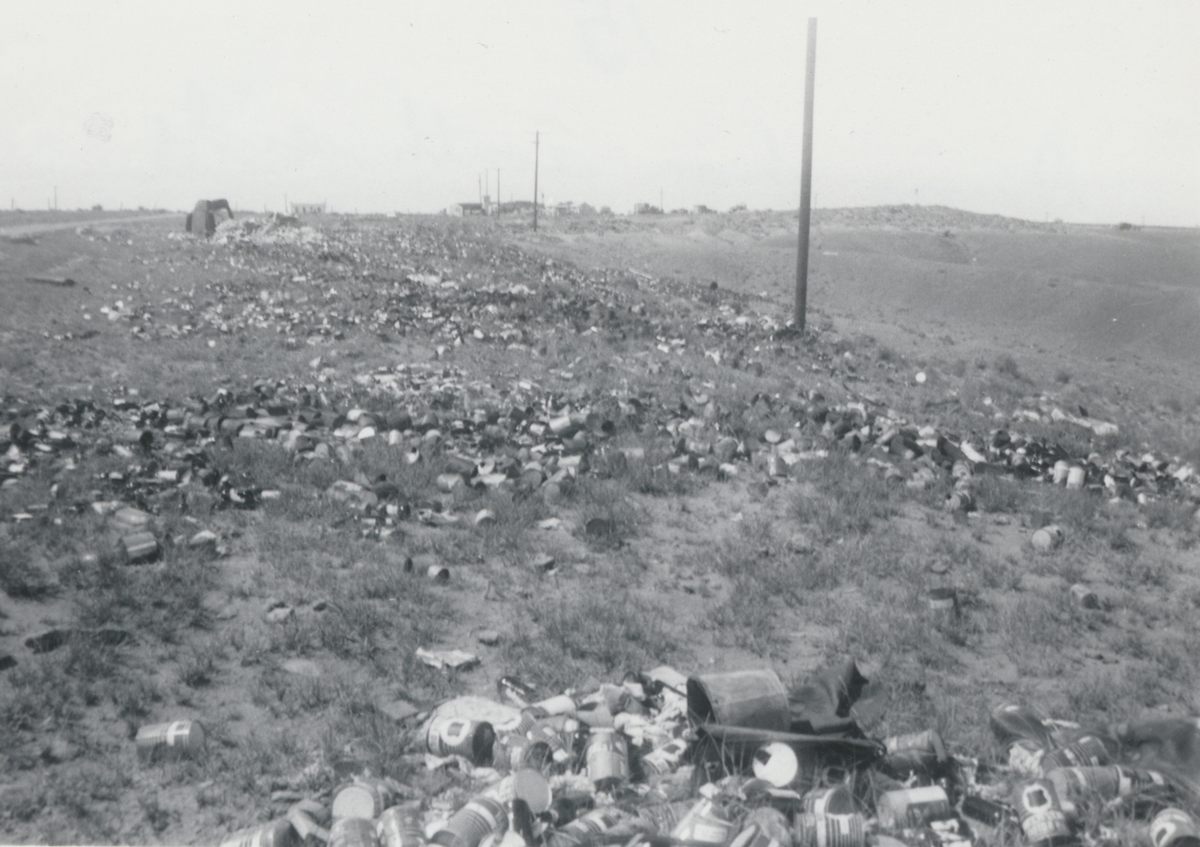

Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona is the only national park that contains a segment of Route 66. The park is famous for its stony, sculptural tree stumps and sherbet-striped desert, but amid the sagebrush are a dozen or so old telephone poles, stripped of the wires that once linked them. That’s the old highway, and it’s strewn with a trove of midcentury trash.

That section of Route 66 was bypassed in 1958 by what became I-40. “Almost immediately after it was bypassed, the park removed asphalt from the surface, but left the roadbed itself,” says William Parker, the chief of science and resource management at the park. The roadbed is composed of the heaps of dirt and aggregate that elevated the road so it wouldn’t flood and wash out in storms, and it was flanked by ditches. That’s where the trash accumulated.

As the remains there show, desert drivers might nurse a 7-Up, or Kist soda, or A-1 beer, an Arizona speciality. When a bottle or can was empty, they just flung it. “It was socially acceptable at the time to just roll down the window and throw the trash out,” says Parker.

The densest concentration of trash came to rest about 10 to 15 feet from the roadbed, in a band Parker and his colleagues affectionately call the “throw zone”—“about as far as you can huck a bottle out of a moving vehicle,” he adds. It was once so thick with garbage that it looked as though someone had torn open a trash bag and shaken its contents loose. Decades later, the “throw zone” is still home to smashed porcelain plates, bits of car door handles and mangled tires, and toys, such as cap guns and marbles picked up at the “trading posts” that once dotted the highway. Accessories such as aviator sunglasses turn up, too. There are easily hundreds of bottles and cans.

Some of the sun-baked, sand-whipped items are too scoured or rusted to read, but their shapes, materials, and mouths are clues to their identity. The cans are largely steel instead of aluminum, Parker says. They might be flat-topped—requiring a churchkey to open in the days before pull tabs—or have a conical top that evokes a can of motor oil. “They’re all from the 1930s to the 1950s, which is exactly what we’d expect,” Parker says, since that’s when the highway was active. Some of the bottles are stamped with the city where they were made. Parker can imagine a family stopping for soda in Gallup, New Mexico, driving west, and then needing to replenish their supply by the time they passed through the park en route to Flagstaff.

Immediately after the highway was torn out, Parker says, park staff did a cursory tidying up of the ditches, but they didn’t pick them clean, and it would have been hard even if they’d tried. Over time, some of the trash was buried by blowing dirt. (At the time, the park and much of the private land around it lacked trash pickup, Parker says. Garbage elsewhere in the park was either burned or deliberately buried.) Now, along the roadbed, more “throw zone” trash is resurfacing as the mounds shift and erode.

Though Route 66 hasn’t existed in decades, there’s still a lot of nostalgia around it. It hits all the most resonant Americana notes—a journey, big skies, no looking back. The road “is a cultural resource in its own right,” says Jason Theuer, now cultural resources branch chief at Joshua Tree National Park, who worked at Petrified Forest in the 2000s. During his time at the park, Theuer says, he met visitors who fondly remembered driving the original route.

In 2006, the park installed a turn-off spot that commemorates the highway with a smattering of little attractions, including an interpretative panel and a rusty, wheel-less 1932 Studebaker propped up on concrete supports. Parker estimates that somewhere between a quarter and a half of the park’s 700,000 to 800,000 annual visitors stop by the display. About a dozen artifacts from the “throw zone,” mostly kids’ toys, are on display in a permanent exhibition at the park’s Painted Desert Inn. A few dozen representative objects have also been added to the park’s museum collection, which is generally locked up in metal cabinets. Elsewhere, the Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program, a Park Service project, has compiled oral histories, preservation reports, and ephemera, and produced an itinerary for contemporary road-trippers, including everything from lodges to chicken joints.

These days, Parker says, “for the most part, visitors are good about putting things in cans.” The only fresh trash he observes are tangles of paper and occasional plastic bags that blow in on gusty fall days.

If you do see some old-looking rubbish in the park, just leave it be: Trash that is more than 50 years old and left in place is considered historic. Think of it as a window into midcentury recreation. “It’s funny that someone would throw these bottles or cans out and not think that in 50 years they’d be in a museum somewhere,” Parker says. “As we progress through time, things are constantly becoming historic.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook