Tour Honolulu’s Japanese Food Scene With This 1906 Map

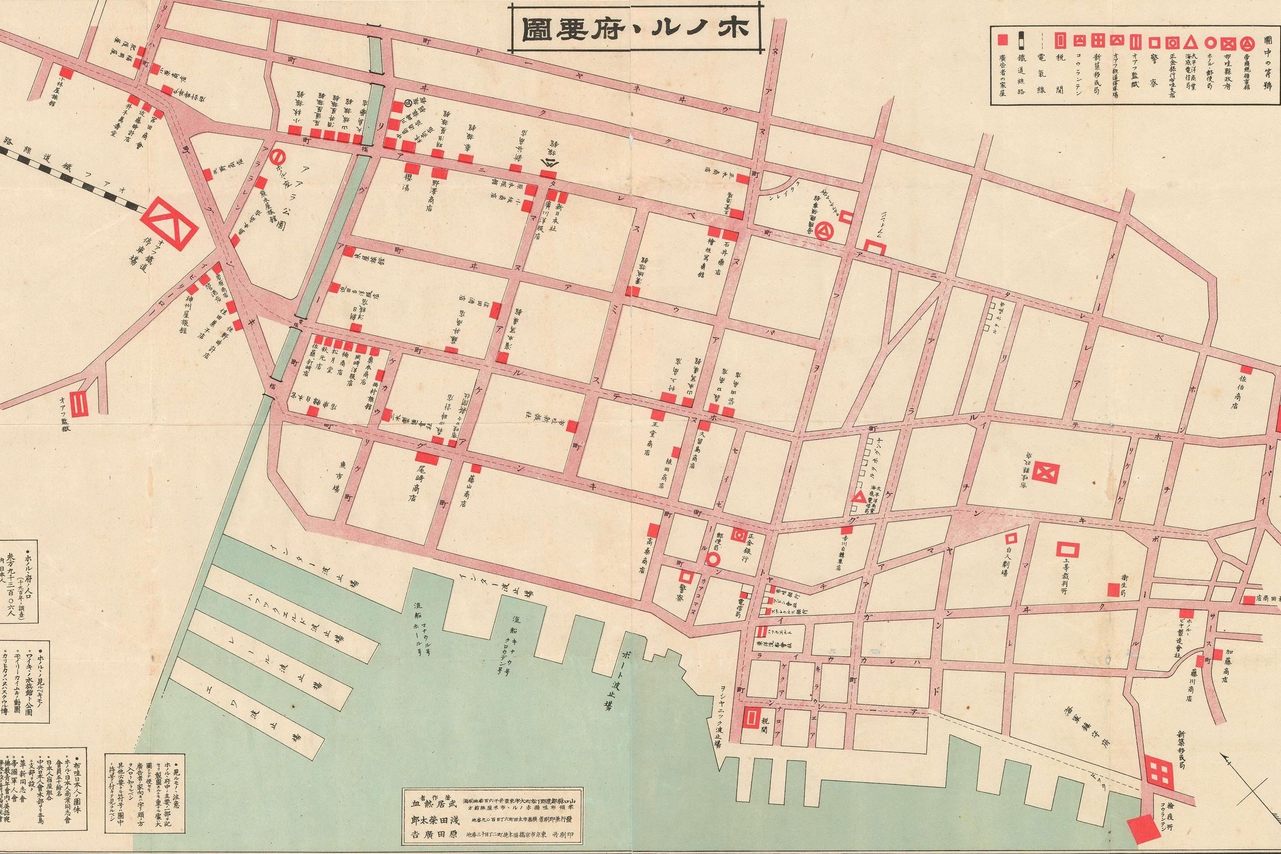

More than a century ago, Takei Nekketsu mapped Japanese-owned businesses for recent immigrants.

We don’t know much about Takei Nekketsu. The proprietor of a dry-goods store, he was one of the many small business owners who made up the thriving Japanese community of early 20th-century Honolulu. But Nekketsu had a number of special talents. He wrote some of the earliest Japanese-language histories of Hawai’i, and he made maps.

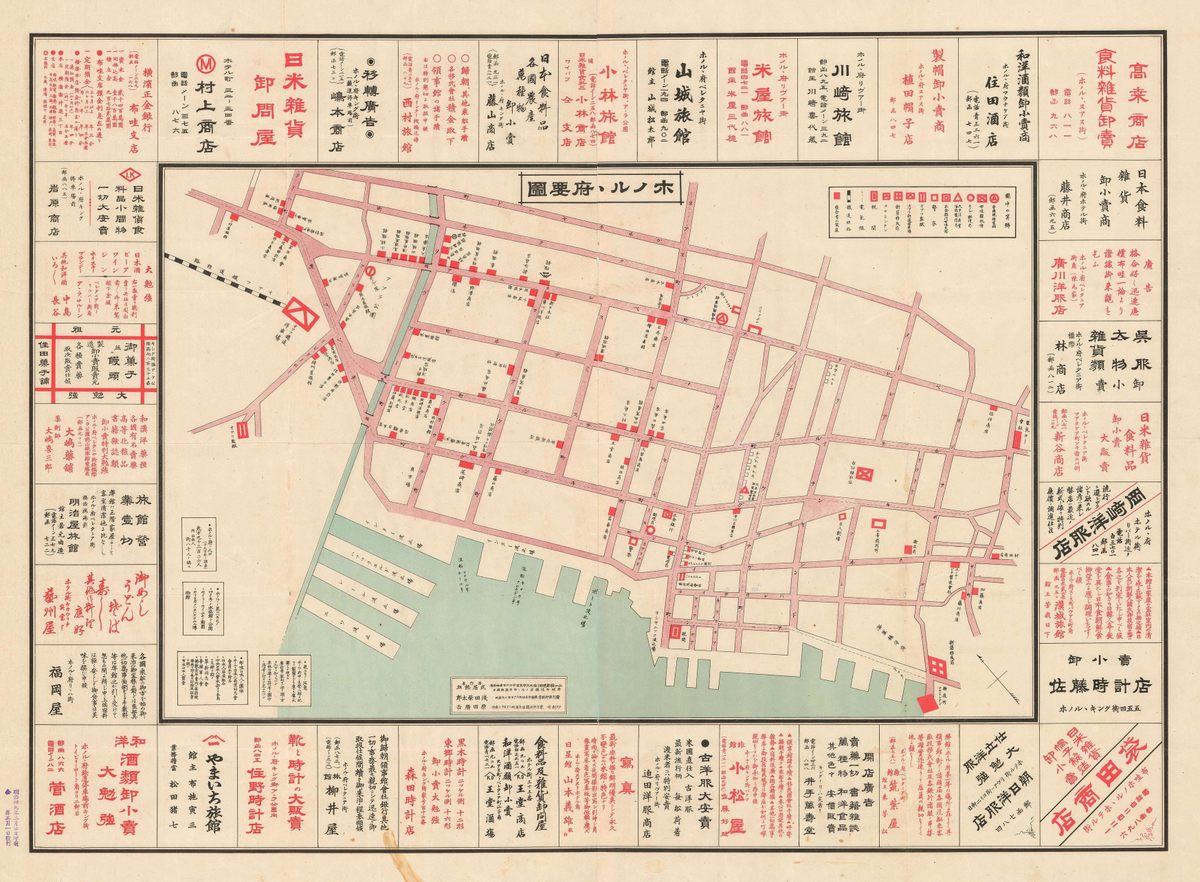

One map in particular, from 1906, shows his skill. Census records don’t tell us if Nekketsu had formal cartography training, but the map’s precisely labelled lines, crisp angles, and delicate calligraphy reveal a practiced hand. And the contents of the map reveal a practiced palate.

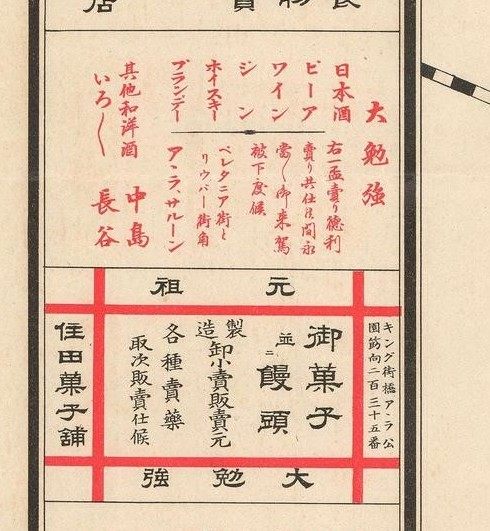

“There’s a store selling Japanese wine, there’s a store selling Japanese confections,” says Li Wei Yang, curator of Pacific Rim Collections at the Huntington Library, which recently acquired two of Nekketsu’s maps. “They’re little grocery stores probably selling things that would cater to Japanese immigrants, that are owned by Japanese immigrants.”

The map is printed on paper, and would have been distributed to Japanese-speaking residents and visitors to Hawai’i. While the city has changed, the map roughly corresponds to today’s Chinatown. Descriptions on the map and notes around its edges advertise steamed buns and Japanese medicine, banks and photo studios. In short, everything that recent arrivals might want to feel at home.

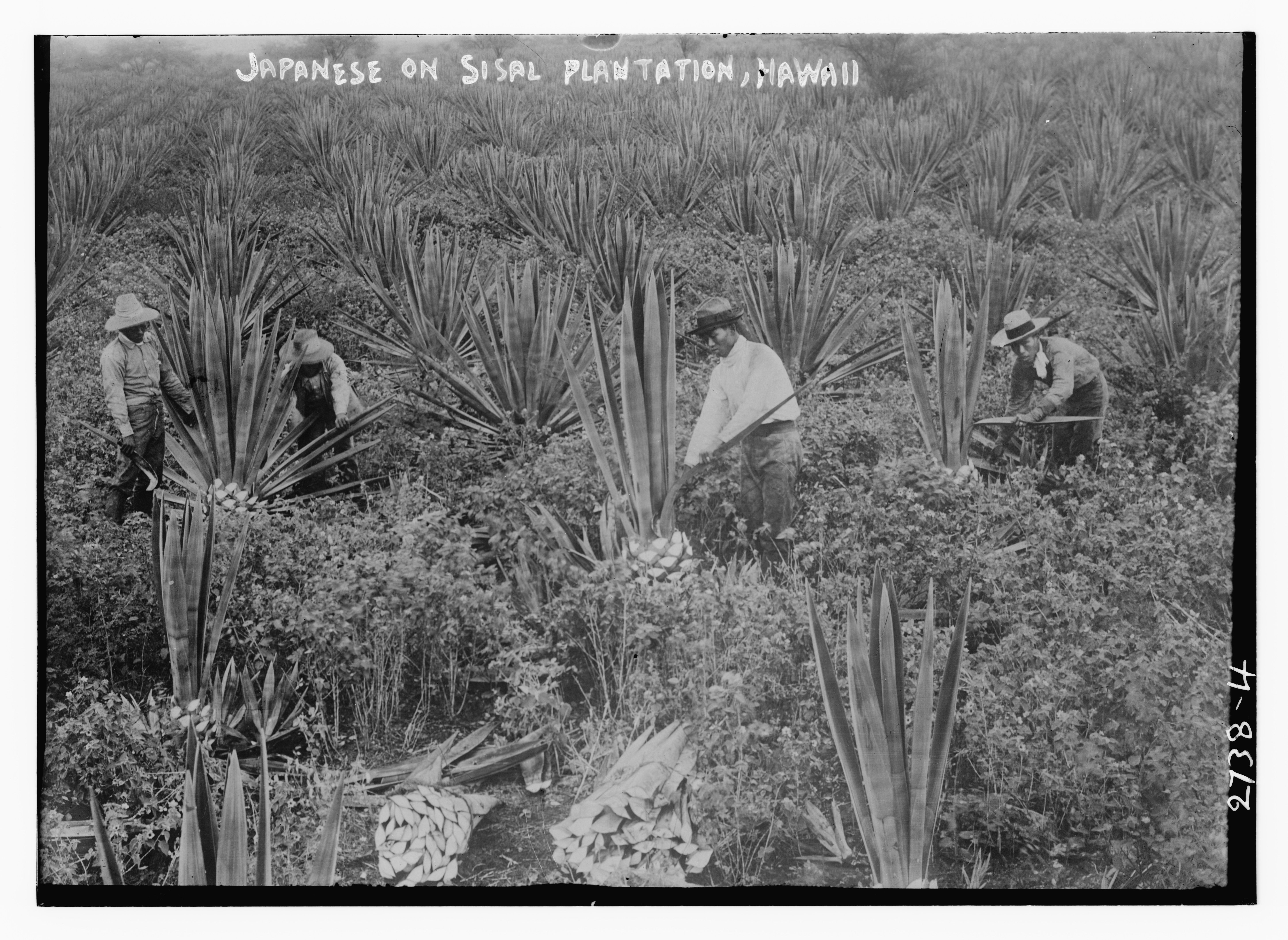

By 1906, Hawai’i had already been home to a Japanese community for several decades. The first group of Japanese immigrants entered Hawai’i in the mid-1800s. They were indentured laborers, recruited from Japan to work on sugar plantations for low pay in brutal conditions. Economic desperation drove them across the Pacific. “Earning a livelihood in Japan at the time was not easy,” says Yang. Land was limited, and most peasants had no path to farm ownership. So in the late 1800s, the Japanese government gave Hawaiian industrialists permission to recruit laborers directly from Japan itself.

By the turn of the century, Japanese immigrants had gained access to greater economic power, becoming key players in the island’s fledgling Kona coffee industry, and opening small businesses alongside Chinese and Korean immigrants in Honolulu’s budding Chinatown neighborhood. By 1940, people of Japanese descent made up around 40 percent of Hawai’i’s population. Nekketsu’s map, made at the beginning of this population boom, reveals a network of businesses for both travelers from Japan and new residents to frequent.

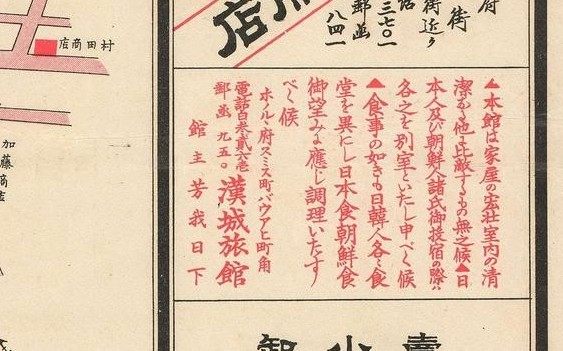

While bakeries and Japanese liquor stores are well-represented on the map, sit-down restaurants are scarce. One exception was the Hanseong Inn, named after the previous moniker of Seoul, South Korea. According to a Japanese-language advertisement on the map, visitors at the hotel could enjoy Japanese or Korean food and meet other new arrivals.

The Hanseong Inn has shuttered its doors, but Honolulu’s Japanese food scene remains vibrant. Visitors today can sample mochi sweets from a shop founded right after the publication of Nekketsu’s map (Nisshodo Candy), eat the clear-brothed saimin noodle soup invented by plantation workers, or have a noodle-and-tempura lunch in one of the many small, local okazuya shops, deli-style eateries that have been around since the 1900s. The establishments Nekketsu mapped may be long gone, but you can still top off your food tour with a modern variant of the same snack Japanese immigrants were greeted with when they arrived in Hawai’i all those years ago: a steamed bun.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook