Dozens of Mysterious ‘Reserve Heads’ Were Sealed in Ancient Egyptian Tombs

Over 30 have been found, but their function is unclear.

In 1894, the French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan made a perplexing discovery in the royal necropolis of Dashur. In a tomb dating around the reign of Snefru (beginning 2613 B.C.) during Egypt’s fourth dynasty, he found an odd sculpture of a human head. This object, known as a reserve head, has puzzled and inspired scholars for over a century.

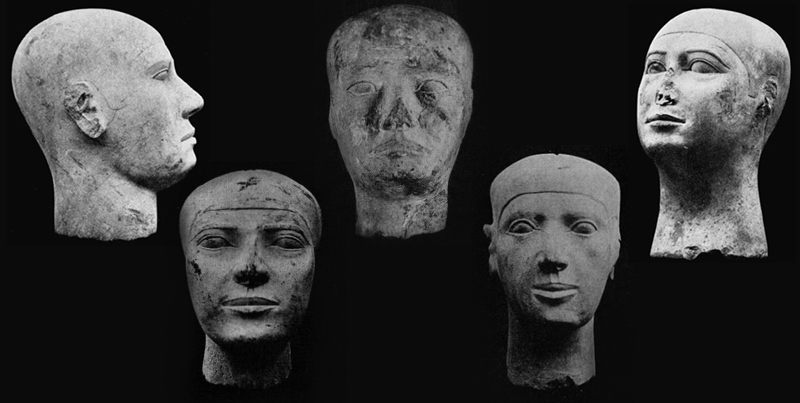

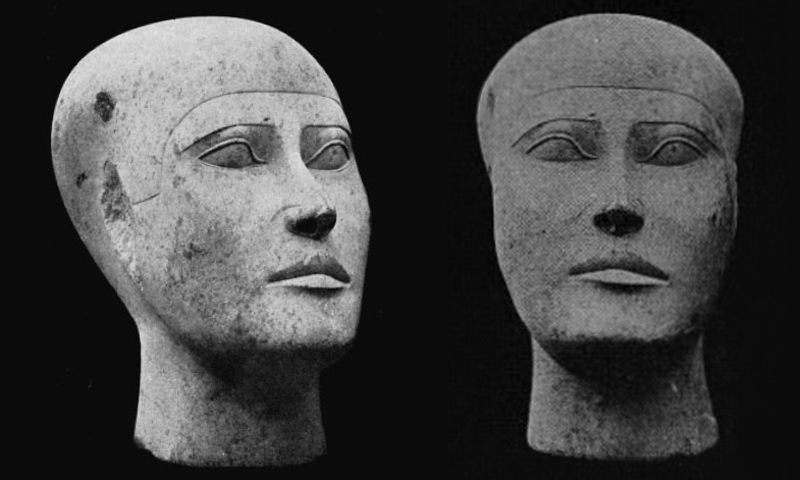

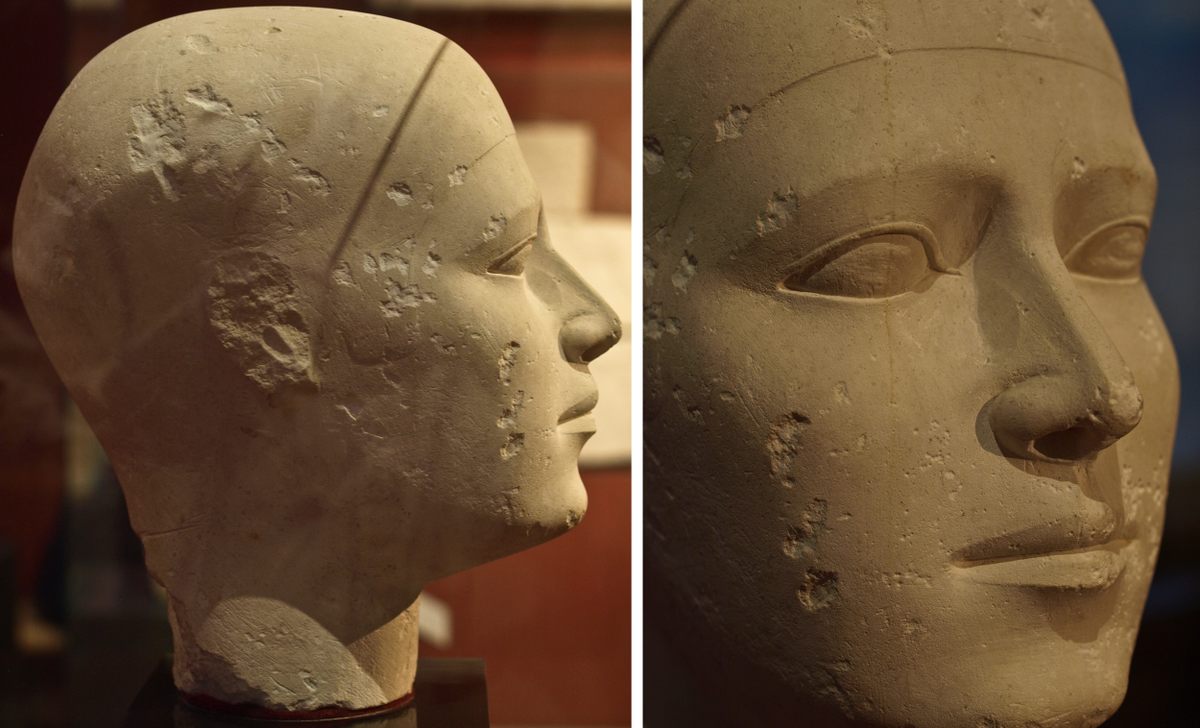

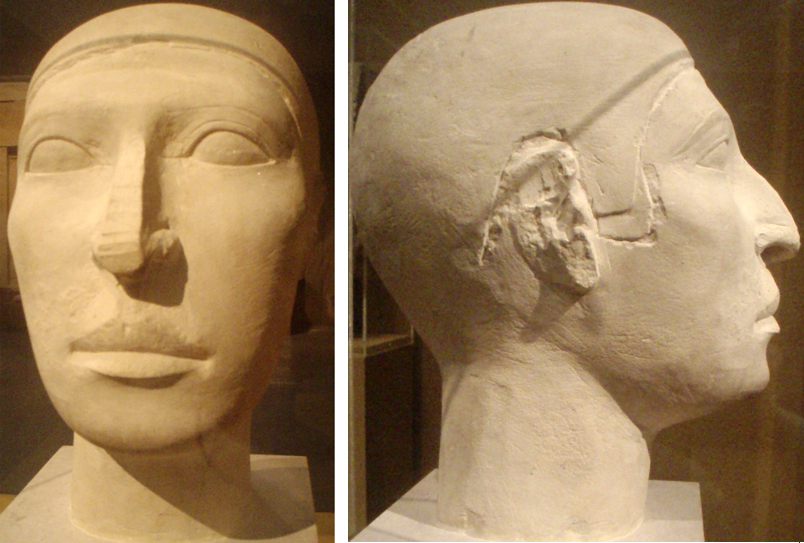

In total, 31 reserve heads have been discovered. Of these, 27 were found in tombs at the royal necropolis of Giza, 15 miles southwest of Cairo. The sculpted heads, found in tombs of aristocrats and members of the royal family, including Princess Meretites III, share many common features. Sculpted during the Old Kingdom (2613-2181 B.C.), the heads are often made of limestone, with the bottom of the neck working as a sort of base to allow the object to stand. The features are soft and at times personalized (perhaps to resemble the deceased inhabitant), and the hair is always shaved or cropped close. There is evidence that at least some of the heads were painted. The remnants of plant-based red paint on one head has led to the hypothesis that it was for some reason painted entirely in a bold red.

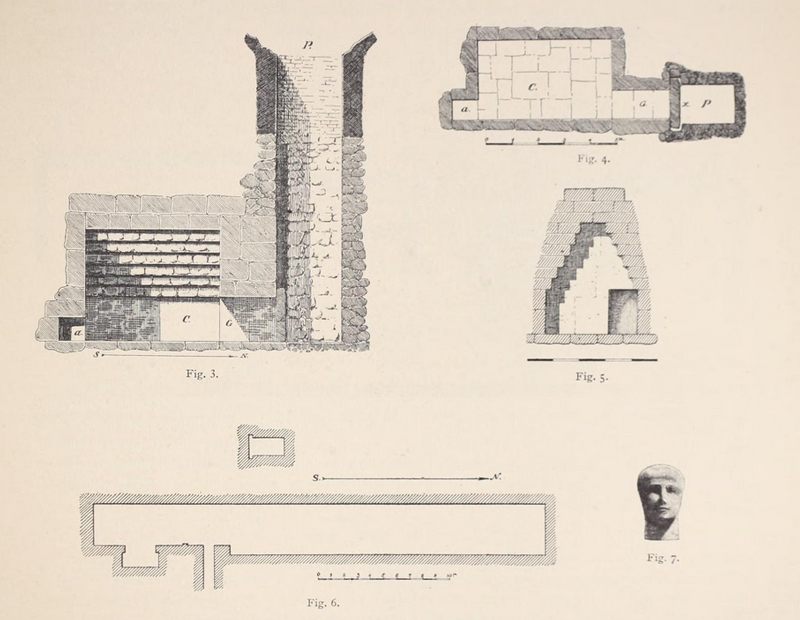

Grave robbers and thrill seekers have looted and scattered the heads over millennia. However, according to Nicholas Picardo, Associate Director at Harvard’s Giza Project, researchers have been able to pin down the heads’ original locations.

“Although all known heads had been disturbed from their exact original placements before their discovery in modern times, all signs point to them having been set up somewhere in the underground sections of tombs, somewhere from the burial shaft to the subterranean burial chamber,” he says. “As a general rule, funerary statues went above ground, ideally in a chapel that was part of the tomb’s superstructure or in a small room built specifically to contain it. Placement underground is quite odd.”

The heads’ functions have been harder to pin down. “In a sense, all tomb statues were stand-ins, or ‘reserves,’ for people whose mortal lives had ended,” Picardo says. “However, the ‘reserve heads’ specifically got their name from an early theory that they were spares—or again, ‘reserves’—to replace a dead person’s actual head in case it was lost or destroyed.” Mummies were often tampered with post-entombment, as a result of natural occurrences or grave robberies.

While this theory has fallen out of favor, it is in a sense accurate. “They were physical representations of the deceased that could be embodied by one aspect of a person’s ‘spirit’ (for lack of a better modern word) when it crossed back into the mortal plane of existence from the afterlife,” says Picardo.

Complicating everything is the fact that a number of the heads seem to have been intentionally mutilated. According to Catharine H. Roehrig, Egyptologist and curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the most common disfigurements include the removal or destruction of the statues’ ears. Many heads also feature scratches or gouges tracing from the top of the head down to the nape of the neck.

There have been several theories put forward to explain the damage. Peter Lacovara, Director of The Ancient Egyptian Heritage and Archaeology Fund, believes the heads were actually sculptors’ guidelines or molds, and thus easily damaged. A bit of plaster on one of the statues has led some to believe that it was perhaps used to make uniform plaster molds of the deceased. And Egyptologist Roland Tefnin surmises that the heads had been symbolically “killed” to protect the deceased.

Picardo’s theory is somewhat similar. He believes the reason the heads were mutilated has more to do with where the objects were placed—underground, in a sealed off, sacred area— than their functions as tomb statuary. “Just like the buried Egyptian was thought to reanimate in the afterlife after proper burial,” Picardo says, “apparently other things could also ‘come to life,’ so to speak, in that potent, sacred space.”

“If a reserve head was thought to depict the deceased Egyptian essentially already in a decapitated state, and their placement in tomb space meant that this could become a terrible reality in the next life, then some sort of fix would have been in order—if not elimination of the reserve heads altogether,” he explains. “Damaging them in relatively minor ways may have accomplished this corrective without destroying them completely.”

Whatever the reserve heads’ real meaning, they offer a personalized, human glimpse at the faces of ancient Egypt. One of Picardo’s favorite statues is of a man known as Nefer/Nofer, now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which has eight reserve heads in its collection. “He has a prominent and particularly shaped nose, a feature that appears also in relief decoration from his tomb chapel. This points to Egyptian sculptors of this time actually trying to capture individual likenesses in the statues they were crafting, as opposed to more idealized or standardized representations of the human form, as was the general rule,” Picardo says. “Although … having a fairly prominent nose myself, it may be that I just identify with him a little.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook