During the Taiping Rebellion, a Stunning 15th-Century Pagoda Met Its Demise

Centuries after the Porcelain Tower was torn down, it was built up again—and this time, made of steel.

When buildings are knocked down, people often don’t let them go without a fight. This week, we’re remembering some particularly contentious demolitions. Previously: a Hollywood funeral for a restaurant named for a hat and a German church knocked down in the name of coal.

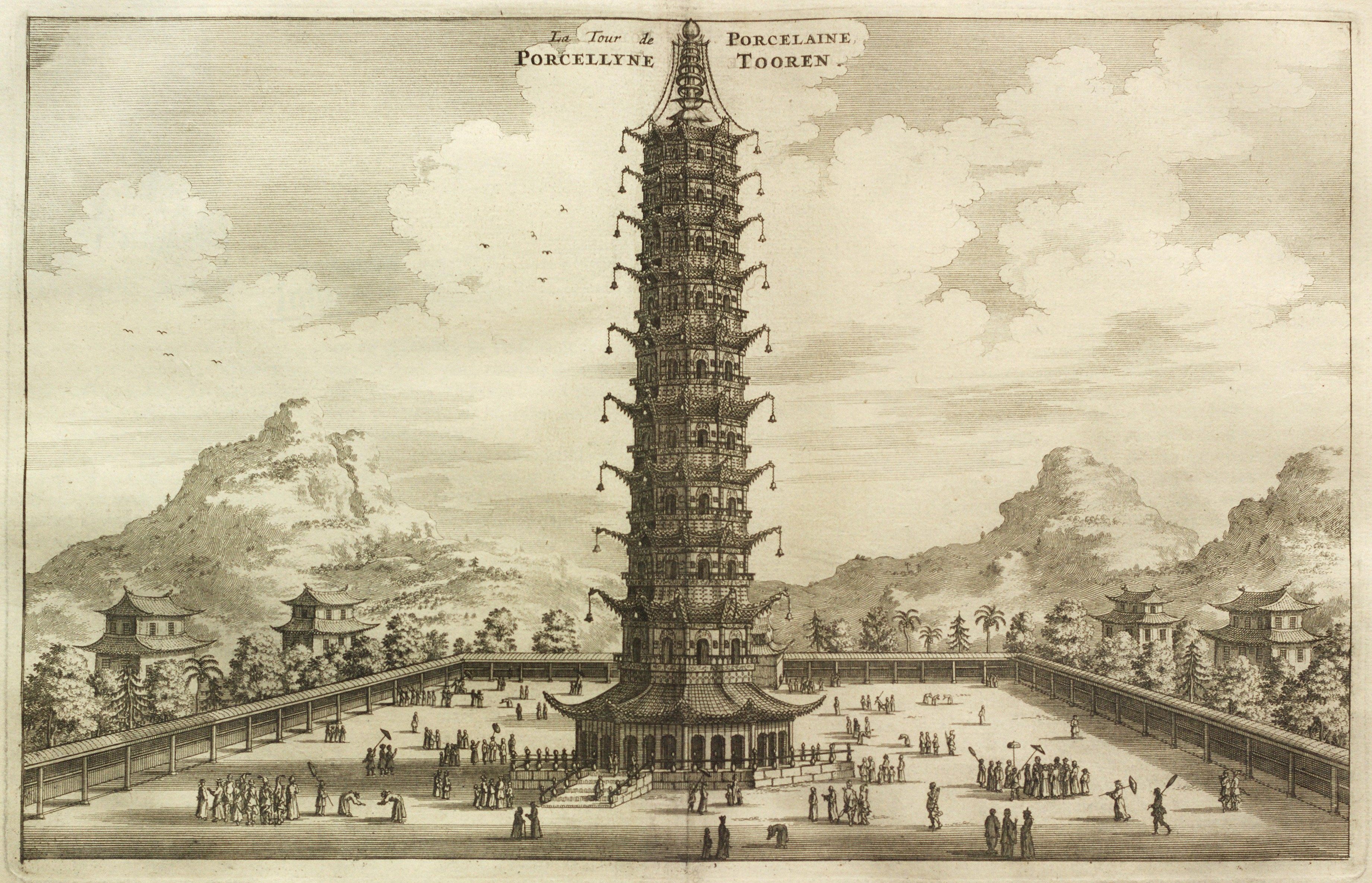

Long before it was toppled in a military skirmish, the octagonal pagoda was said to have caught travelers’ eyes from miles away. It rose nine stories tall, and was crowned by a giant decoration shaped something like a pineapple. In engravings and other artistic interpretations, it seemed to rival nearby mountains, its top nearly level with a smattering of birds and almost piercing the clouds—taller than anything else in sight.

Built in the 15th century at the behest of the Yongle Emperor—who is said to have designed it as a tribute to his parents and the tradition of filial commitment—the so-called Porcelain Tower was part of a complex known as the “Bao’en Temple,” or “Temple of Gratitude.” The tower soared above the landscape around Nanjing. Visitors who scaled the 184 stairs all the way to the top would be treated to a view of the whole city, snaking rivers, and beyond, recalled Johannes Nieuhof, a Dutch traveler, when he stopped by in the mid-1600s.

However striking it appeared from a distance, up close, “it more than realized our expectations,” Granville Gower Loch, a captain of the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy, wrote in 1844. The pagoda was made of creamy porcelain, interspersed with tiles covered with colorful glazes. The cumulative effect, when the sun glinted off of it, was “a glittering light like the reflected rays of gems,” Loch wrote. The tower was festooned with scores of lamps and bells, which “used to ring forth charming melodies,” Loch reported, but were now “tongueless, and all of them cracked.”

If any of the bells could still clang during Loch’s visit, they would all fall silent by the 1850s, when the structure is said to have been stripped of Buddhist imagery and eventually ripped down by rebels during the Taiping Rebellion—much to the dismay of those who considered it one of the architectural jewels of the medieval world. One explanation for the destruction is that the same height that once afforded visitors such a sweeping view of the landscape could also be used for tactical purposes, allowing other troops a useful vantage point across great distances.

Some of the bricks were salvaged from the rubble, and eventually entered museums. The former tower climbed into public consciousness again more than 150 years later, when archaeologists excavating its footprint claimed to have come across Buddhist relics in a crypt beneath the site.

The finds seemed to heighten the sense of loss surrounding the long-gone tower, and a real estate magnate reportedly ponied up one billion yuan (roughly $150 million) to fund the construction of the Porcelain Tower Heritage Park, which exhibits artifacts and a new version of the tower itself.

The slicker, sleeker version went up in 2015. This modern rendition was fashioned from glass and steel, echoing the skyscrapers off in the distance—all of which Loch, Nieuhof, and their contemporaries wouldn’t have seen. A lot has changed in nearly 600 years, but the new tower still cuts a striking silhouette.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook