Pop Culture Gargoyles Hidden in Gothic Architecture

Bring binoculars.

Fascinating ghouls of another era, gargoyles emerged around the 13th century in European architecture with a vast array of form and function. At first, they were designed as an indispensable engineering trick. Projected from roofs at parapet level, the strange leaning creatures created a siphon for rainwater to protect the walls of the edifice. They evolved to become “grotesques, ” ornamental elements with a specific symbolic charge. With their demonic grins and anthropomorphic shapes, gargoyles and grotesques were used to visually exemplify the concept of evil and virtue at a time when a large part of the population was illiterate. Beyond their moral function, gargoyles also had an “apotropaic” value: their grimacing faces were believed to avert the evil eye and keep it from the sacred space.

Gothic architecture was later revived in the 18th and 19th century in England and the United States. Naturally, gargoyles became one of the stylish signatures of this new Neo Gothic architectural type. But centuries of capricious weather and a lack of care had disfigured the legions of statues that were still silently guarding the old gothic monuments. A large amount of stunning chimeras were actually falling to the ground like a plague rainfall. In order to remedy to this situation, conservation programs were started for some of them, and 20th and 21st century stone carvers were asked to replace as many destroyed gargoyles as possible. If some of them copied meticulously the medieval form of the past, others had another vision of what gargoyles could be.

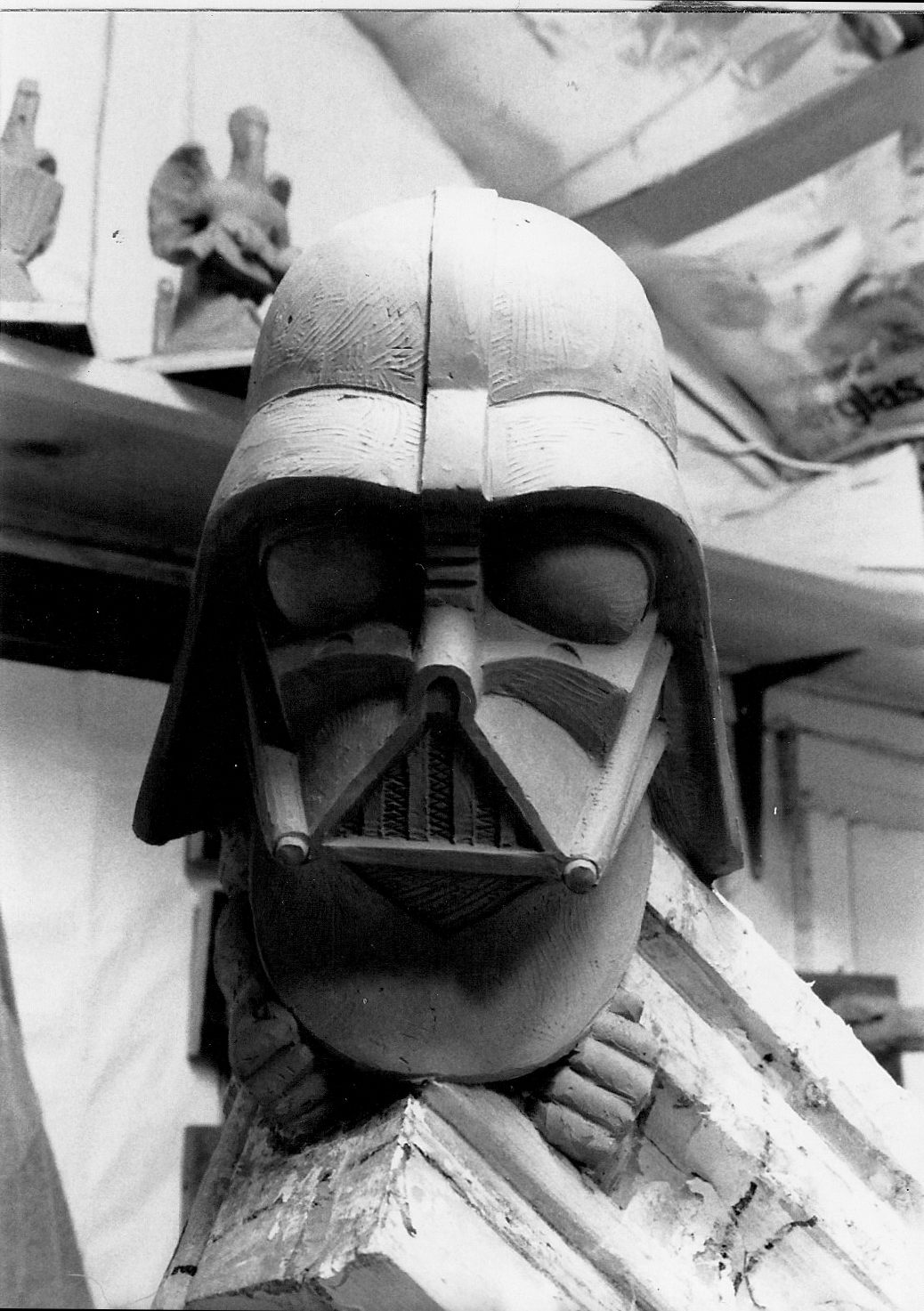

Many of these examples are unfortunately high on the façades out of sight, but a pair of binoculars might help you out. In the 1980s, Washington National Cathedral became one of the first to experiment with of gargoyle reinterpretation. Some of you might have heard the story of the most famous one: the Darth Vader gargoyle, who was the winning proposal in a children’s contest organized by National Geographic. Christopher Rader, a 13-year-old kid from Nebraska, created its design, envisioning the Star Wars villain as a modern incarnation of supreme evil. Sculpted by Jay Hall Carpenter and carved by Patrick J. Plunkett, our dark-sided Anakin is today on the Washington Cathedral, wearing his iconic helmet on the first tiny peaked roof from the center pinnacle, on the right hand side.

If you’re curious enough for a gargoyle safari, stay around the edifice! You will not be disappointed, as Darth Vader is just one of many pretty unusual creations conceived to adorn the National Cathedral. The 112 sculpted gargoyles include those by Walter S. Arnold, who envisioned gargoyles as portraying the specific hopes and fears of their era. Arnold’s sculptures have name like “The Crooked Politician,” “The Fly holding Raid Spray,” or the “High Tech Pair,” representing a stylized robot and surveillance camera.

As representations of our contemporary life, it’s now not uncommon practice for stone carvers to integrate, here and there, images of our present. The mysterious astronaut, tangled in floral motifs, is not a visionary medieval anticipation of our space travels, as one rumor said. It was created on the façade of the Salamanca Cathedral in Spain in 1992, during a renovation.

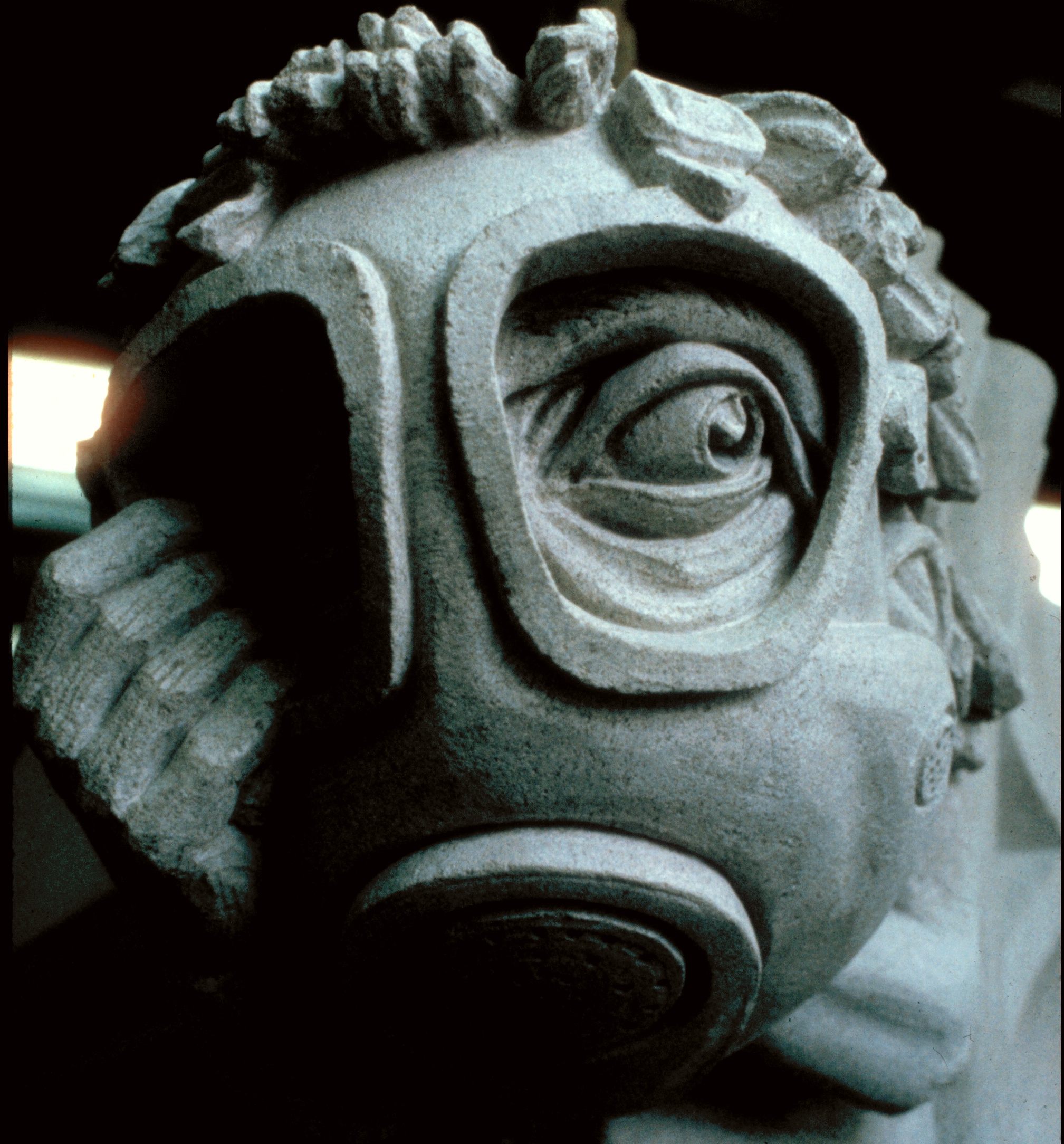

Another story of delightfully iconoclast restoration took place in France, a few miles away from Nantes, in one of the major historic cities of Brittany. In 1993, in Saint Jean-Boisseau, the late Middle Ages chapel of Bethlehem was subject to a renovation. Since almost none of its pinnacles had survived, a decision was made to replace them one by one, while keeping the traditional symbolism attached to each of them. With this in mind, stone carver Jean-Louis Boistel, proposed to restore the traditional archetypes with more modern ones, directly drawn from pop culture.

Thereby, the anime robot Grendizer became the image of a modern knight’s righteousness, Gizmo the standard for our “good” inner self, while his alter egos the Gremlins, for the bad. However, Boistel’s boldest choice may be the representation of the “Leviathan,” a figure of the uttermost chaos, represented by a Giger-inspired Alien. Boistel’s “geek chapel” wasn’t initially popular with the villagers, but the local enthusiastic youth helped make it a reality.

Just as Catholic sacred architecture used to be like a historical picture book, describing Middle Ages ways of life, so is adding a modern motif of modern monsters like the “ear mouse” grotesque of Saint George’s Chapel (inspired by Dr. Charles Vacanti’s experiments) reactivating the traditional function of Gothic Architecture.

Talking about polemics, our last example probably spilled more ink than rainwater, and occurred a couple of years ago in the French city of Lyon. The Cathedrale Saint Jean, already in the Atlas for its incredible Astronomical Clock, now has another wonder. During the renovation of the cathedral, stonemason Emmanuel Fourchet created a gargoyle figure after his construction manager, Ahmed Benzizine, as a token of their friendship and appreciation for his dedicated work. Ahmed is a veteran in historical renovation and has spent more than 30 years of his life restoring religious structures in France. He’s also a Muslim.

Conservative groups furiously criticized the act, calling it blasphemy. While the Archbishop saluted this gesture as an meaningful act, he also underlined the fact that the extreme reaction was due to a lack of understanding of the history and culture concerning the sculpted art of the cathedral itself. The Church Rector Chanoine Michel Cacaud reminded the public that the elements adorning the outside of the cathedral are meant to represent the profane world in its complexity. And now they can reflect those same complexities of our contemporary world.

The story originally ran on June 10, 2013, and has been updated with new images.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook