During WWII, Polish Refugees Found a Home in India

The Maharaja of Nawanagar opened his summer palace to displaced children.

When he was only six years old, Feliks Scazighino and most of his family were deported from Poland to a Siberian gulag. They remained there for almost two years. Like many refugees, when he was finally released from his imprisonment, he had nowhere to go. That is, until a Maharaja from India opened his doors to Scazighino and nearly a thousand Polish children.

“I was with my mother, my brother, our nanny, my grandparents, and an aunt,” Scazighino recalls. “I remember our life in Siberia, all our illnesses and deprivations and hunger. When we got out of Russia and reached Tehran, we looked like skeletons. We all had to be deloused, our hair had to be shaved off, and our clothes burned.”

For Scazighino, now in his 80s and living in Canada, it is hard to share the story of his childhood. He is from Kresy, which was in the eastern part of Poland. Kresy was invaded by the Soviet Union in September 1939, just days after the German occupation of Poland’s western territories that triggered World War II. The Soviet atrocities in eastern Poland included mass arrests and massacres, expropriation of land and businesses, and the displacement and enslavement of the civilian population.

“Of the estimated two million Polish civilians deported to Arctic Russia, Siberia, and Kazakhstan, in the terrible railway convoys of 1939-40, at least one half were dead within a year of their arrest,” writes the historian Norman Davies in Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland’s Present. When the Soviets joined the Allied powers in 1941, many of the deportees were released, but because of the ongoing war, there was no homeland to which they could return.

And so release was just the beginning of a long and extraordinary journey. Many of the men joined the Polish Army, while the women and children were evacuated to Iran and eventually given asylum in countries as far away as Kenya, New Zealand, Mexico, and India.

“I was about eight and my brother, Roger, was six-and-a-half years old when we reached Bombay,” says Scazighino. Their mother had to stay back in Tehran, which had been their first stop upon release. “After about three months in Bombay, we went by train to Jamnagar, to the camp prepared by the Maharaja of Nawanagar.”

It was in India, where Scazighino spent 18 months, that he went to school for the first time and could finally reclaim some part of his lost childhood. “We met the Maharaja only a couple of times,” he says. “I do not remember him well, but I remember going to his swimming pool where the older boys taught me how to swim by throwing me into the pool.”

In 1942, India was under British rule and going through a volatile nationalist struggle, which would culminate with independence in 1947. Maharaja Digvijaysinhji, also known as “Jam Saheb,” who served on the British Empire’s Imperial War Cabinet, was the ruler of Nawanagar, a princely state (a state governed by a native Indian ruler) in British India. When the British decided to accept Polish refugees into India, the Maharaja offered to host them in his state. A settlement was built for refugee children in Balachadi, on the coast of western India, at the site of his summer palace.

“For my sister, it was the first time in her life that she had some stability and a sense of ‘home,’” says Danuta Urbikas, a writer who lives in Chicago. Urbikas, who was not a refugee herself, has explored the story of her mother and half-sister in My Sister’s Mother: A Memoir of War, Exile, and Stalin’s Siberia.

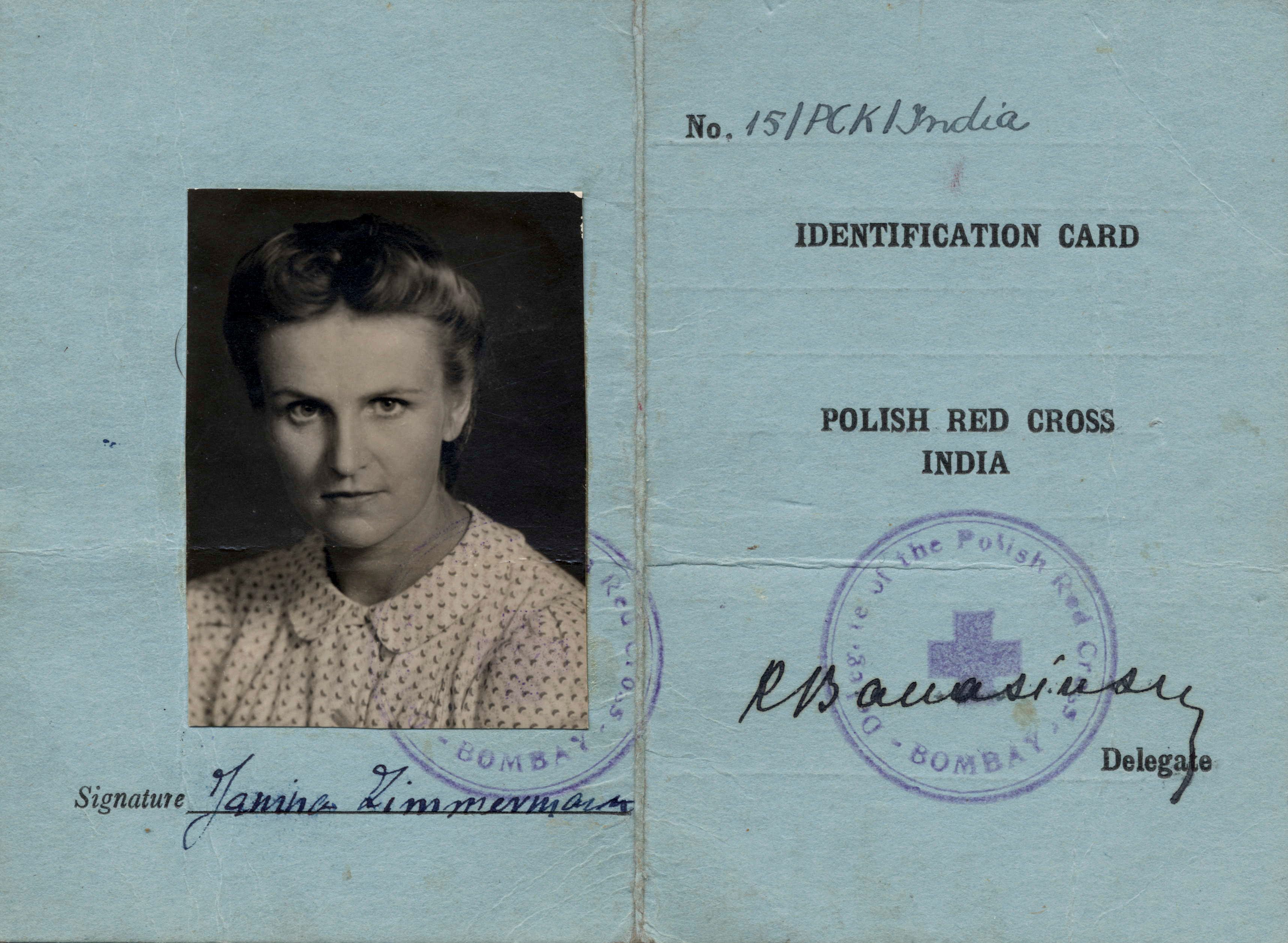

“After having gone through the horrors of deportation from Poland and enslavement in a Siberian labor camp, the terrible journey to escape through Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan into Iran, enduring diseases of all sorts, starvation, witnessing hundreds of people dying, India was a blessing!” she says over email. Urbikas’s mother was a nurse with the Red Cross. They lived in India for five years, two of which they spent at the Maharaja’s estate in Jamnagar and the rest in Bombay.

It is estimated that, nearly 5,000 Polish refugees from Soviet camps lived in India between 1942 and 1948, although researchers have not been able to establish the exact numbers. Multiple transit camps were set up in different locations in India for refugees who were crossing over from Iran to other places. The Maharaja’s gesture was followed by a second and larger settlement for older Polish refugees, organized in 1943. The latter camp was set up in Valivade, in what was then the princely state of Kolhapur and what is today the state of Maharashtra.

The Maharaja already had an abiding interest in Poland, an outgrowth of his father’s friendship with the Polish pianist Ignacy Paderewski, whom he remembered meeting in Geneva as a child. In an interview to the weekly magazine Poland, Jam Saheb explained why he had offered to provide shelter: “I am trying to do whatever I can to save the children; as they must regain their health and strength after these dreadful trials, so that in the future they will be able to cope with the tasks that await them in a liberated Poland.”

The settlement at Balachadi was exclusively for children. According to Wiesław Stypuła, who was one of the child refugees, many of the children were orphans. Others only had one parent. Some parents had gone missing, while others had joined the Polish army, which was being assembled in the Soviet Union. “Please tell the children that they are no longer orphans because I am their father,” Stypuła quotes the Maharaja telling one of the organizers of the camp.

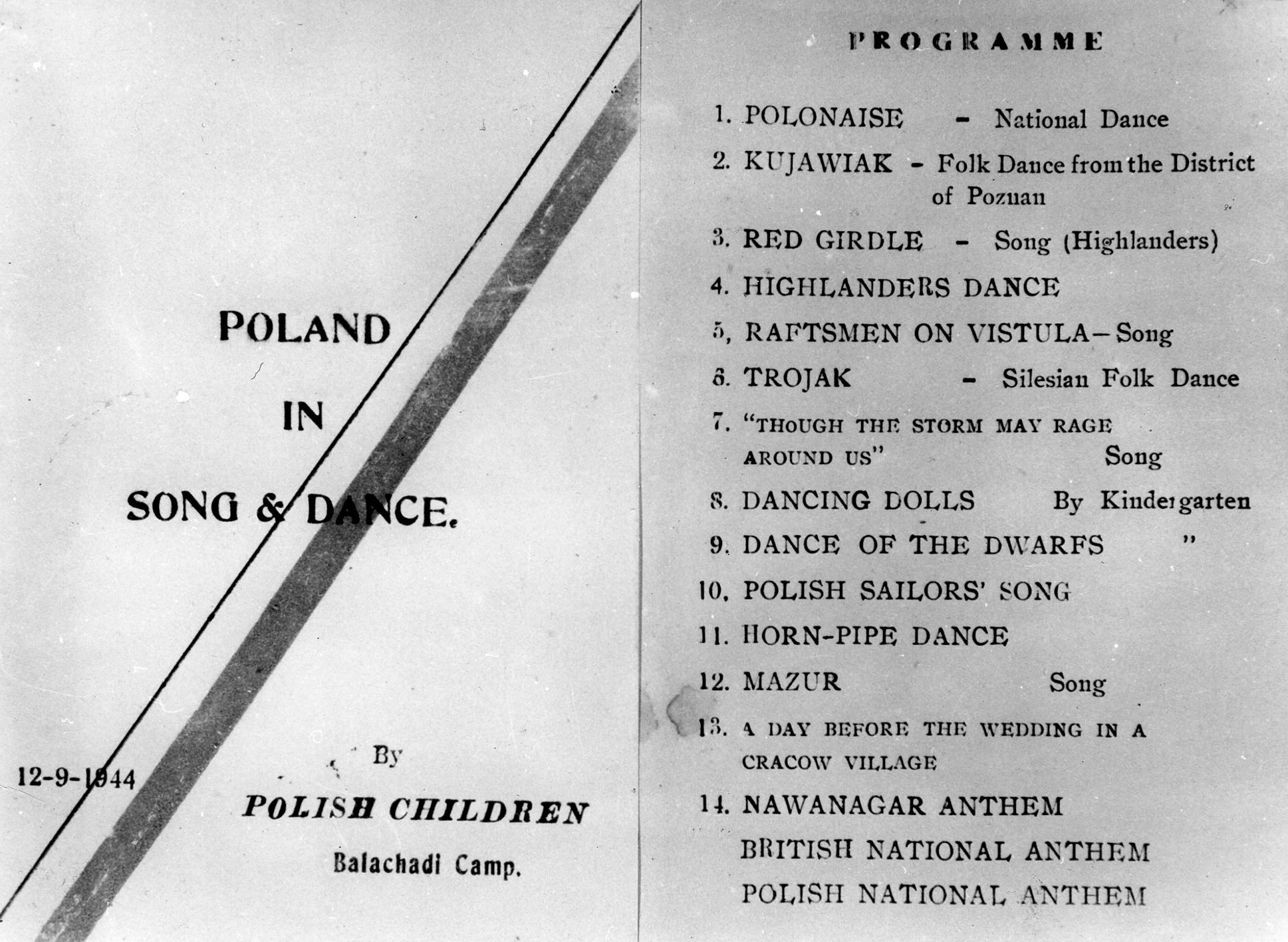

Far from the ravages of the war, life in Balachadi, as described by Stypuła and other survivors, was warm and cheerful. Every effort was made to create a home away from home. The children were provided with housing and education. A school and a hospital were built. They were free to use Jam Saheb’s gardens, squash courts, and pool. The preservation of Polish culture and tradition was greatly prioritized and a Polish flag was raised at the site. Scouting and church, institutions that were integral to Polish life, were built in the “Little Poland” that sprung up in India, writes Anuradha Bhattacharjee, an academic and researcher in her book, The Second Homeland: Polish Refugees in India. (The refugees referred to the settlement camps in India as a “Little Poland,” a term that caught on with those who have documented the story.)

Bhattacharjee says that what the Maharaja did was an example of the ancient and popular Sanskrit philosophy of vasudhaiva kutumbakam (“the world is one family”). “India was not the richest country, nor was it a neighboring country,” Bhattacharjee says, “and yet a quirk of events led to seemingly unrelated people getting together and finding a humanitarian solution.”

Princess Hershad Kumari and Prince Shatrusalyasinhji, the biological children of Jam Saheb, were the same age as the children at the camp. Though they were not available to comment for this story, they have shared their memories, in a documentary and elsewhere, of growing up alongside the Polish children, of playing with them, celebrating Indian festivals and Christmas, and gifting them Indian costumes.

Eighty-two-year-old Sukhdevsinhji Jadeja, Jam Saheb’s nephew who also grew up in Jamnagar, remembers his time at his uncle’s property well. “My uncle did not just accommodate [the refugees], he adopted them,” Jadeja says. “I remember having football matches with the boys from Balachadi. As we grew up, the story was passed down in our family as a good deed that we all took great pride in.”

As World War II drew to a close, the question of repatriation of the refugees was foremost at both Balachadi and Valivade. While some did return to communist Poland, many did not. Those who opted for another path started a long journey towards the U.K., the U.S., and Canada.

Scazighino’s personal odyssey after leaving India is typical of the sorts of arduous journeys the refugees had to make. With his brother, he left India for Tehran to be with his mother. After waiting for six months in Tehran, Scazighino’s mother and her sons went through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon to Palestine, where his mother fell ill for three months. Once she recovered, they traveled on to Port Said, where they boarded a ship to Glasgow and finally London. In London, they reunited with Scazighino’s father. His father had been posted as a reservist to Romania, and went from there to France. After the Fall of France, he traveled through North Africa and eventually to London, where he worked for Polish Radio. And that’s where the family reunited.

“If I had stayed in Poland and there was no war, I would have been a spoilt little rich boy,” Scazighino says. “Instead I was a poor immigrant in a world not too friendly to poor immigrants.”

While the world was in turmoil in the aftermath of the war, India was going through its own turbulent times. The country had gained independence from colonial rule and a way of life was disappearing forever as the princely states were merged into one country. The story of wartime refugees and the generosity of princes slowly started fading as India was grappling with the challenges of nation-building. But the refugees carried the story in their hearts to different parts of the world.

Decades later, Jam Saheb is considered a Polish hero. He was posthumously awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit, one of the highest honors in Poland. In the heart of Warsaw lies the Square of the Good Maharaja (Skwer Dobrego Maharadzy), a cozy space with trees and benches in the central district. Not very far from it is one of Warsaw’s foremost private schools, the Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijaysinhji High School. In 1999, 10 years after the end of communist rule, the Bednarska High School chose the Good Maharaja to be its patron. It was the fulfillment of a promise made long ago. General Władysław Sikorski, Prime Minister of Polish Government in Exile, had asked the Maharaja, “How can we thank you for your generosity?” The Maharaja replied, “You could name a school after me when Poland has become a free country again.”

“The Maharaja set an extraordinary example of generosity and acceptance. This story is our inspiration,” says Barto Pielak, vice principal of Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijaysinhji High School. The school emulates the Maharaja’s example, by accepting children of political refugees and migrants in difficult economic or social situations. “Each year more and more people learn about the attitude shown by our patron Jam Saheb, which is specifically significant while Europe struggles with the issue of massive migration.”

This story of hope would have likely been buried, were it not for the tireless work of the refugees themselves to keep it alive. Both Scazighino and Urbikas shared their testimony over email after I found them online through a group of Polish survivors called Kresy-Siberia, with members scattered all over the world. The individuals who moved to the U.K. formed an Association for Poles in India and meet every two years for a reunion. Through the decades, they have organized regular trips to India. A few years ago, some of the Maharaja’s “children” visited Balachadi and installed a plaque at the site where a school was constructed after the settlement was dismantled.

In September 2018, to mark the centenary of Polish independence in November, the Embassy of Poland in India brought some of the survivors to Balachadi for a commemorative event. Relations between India and Poland are still defined by this wartime story. Adam Burakowski, Ambassador of Poland to India said, “We are very grateful to the Maharaja for offering a safe sanctuary and somehow preserving the childhood of these children.”

In the current global context of the backlash against migration, this story of displaced Polish civilians finding a home in a remote but hospitable land is worth retelling.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook