The Weirdly Ornate Jars Designed Just for Precious Leeches

Victorian leech jars were beautiful—if somewhat ineffective—vessels for keeping the worms alive and out of sight.

Sometime around the turn of the 21st century, pharmaceutical historian W.A. Jackson was in need of a place to keep his leeches. Such is the life of a pharmaceutical historian. He settled on a toffee jar, covered with gauze held in place by a strong rubber band around the rim. Jackson, a former curator at the Manchester Medical School Museum, awoke the next morning to discover three of the leeches had wormed their way through the gauze and disappeared. He tracked down two in his dining room, but the final leech remained on the lam until Jackson stumbled upon it two weeks later, reclining on the turntable of his music console and still, strangely and miraculously, alive.

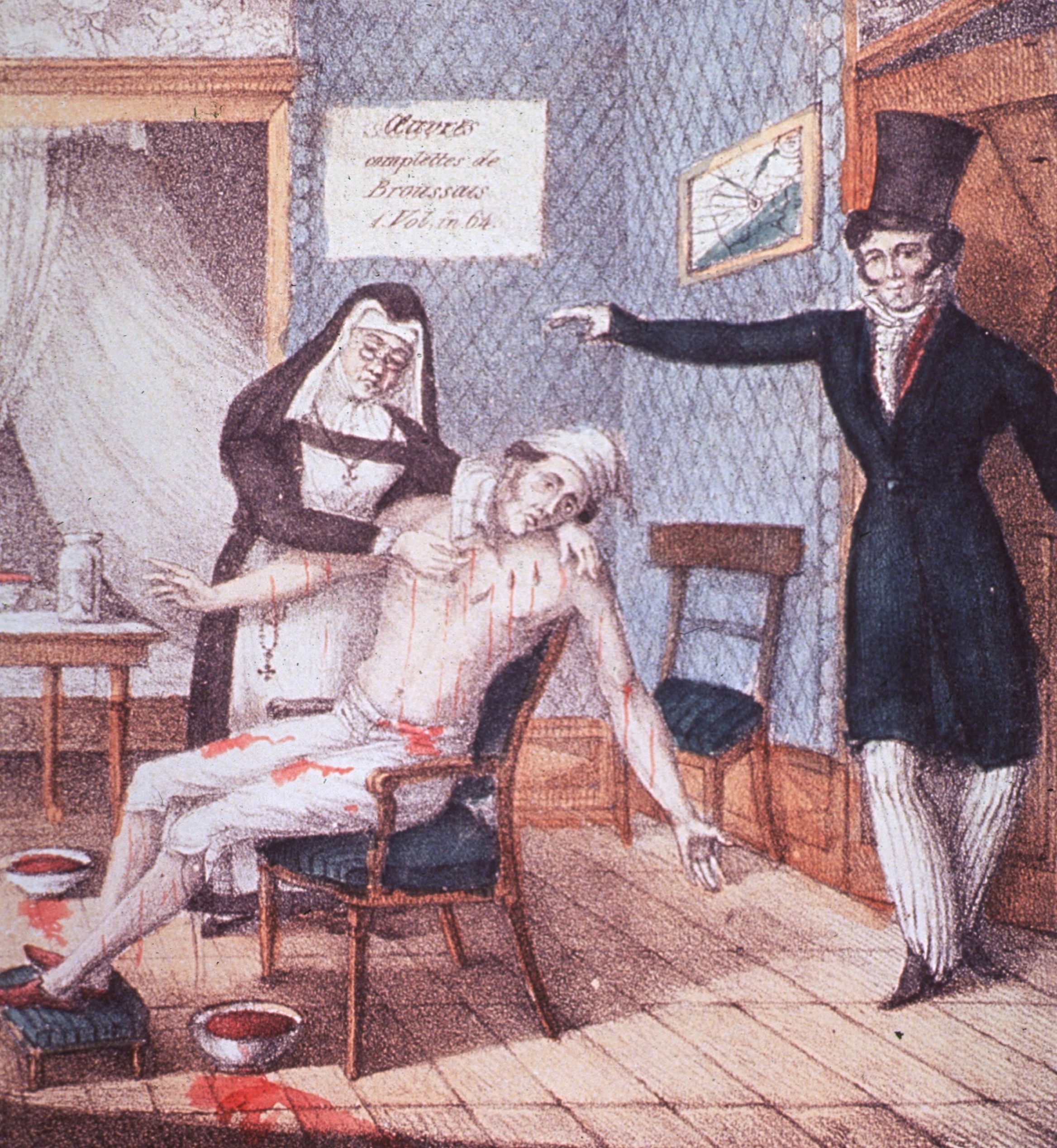

What Jackson needed, he realized, was a proper leech jar. Unlike other, more inanimate pharmaceutical goods, leeches are master escape artists. So enterprising 18th-century pharmacists devised a somewhat special contraption to keep them alive and in check, Jackson wrote in the 2004 issue of Pharmaceutical Historian. Though humans have used leeches for clinical bloodletting—dubiously and, in some cases, legitimately—for at least 2,500 years, the 19th century saw a “leech mania” invade Europe and America. The mania originated in France, where the military medical officer François Joseph Victor Broussais preached an almost vampiric enthusiasm for the therapeutic effects of bloodletting, and it quickly spread from there.

People believed leeches could cure everything from headaches to insanity, and demand became insatiable. In France alone, physicians used more than a billion medicinal leeches a year, and anywhere from 50 to 100 million more were carted across Europe via mule train each year. Wild populations of leeches in Europe nearly went extinct due to overzealous local harvesting. Across Europe and America, elaborate, eye-catching leech jars took over window displays of most respectable pharmacies. These ridiculously rococo ceramic jars sported gilt and hand-painted decorative flourishes, in sharp contrast to their monochromatic inhabitants.

From a modern perspective, in which we expect our pharmacies to be only clean, well-lit, and well-stocked, the existence of leech jars seems entirely unnecessary, for multiple reasons. But American pharmacies had always trailed behind their more chemically savvy and experimental European counterparts in expertise and technology, according to Gregory J. Higby in his article “Chemistry and the 19th-Century American Pharmacists.”

To catch up and earn Europe’s respect, American pharmacists leapt to distinguish themselves from traditional herbalists or lowly homeopaths, Higby writes. In 1852, the creation of the American Pharmaceutical Association established the idea of a professional pharmacy in America, setting certain expectations for aspiring practitioners. Pharmacies began posting their newly required licenses and purity standards. And they carefully cultivated storefronts designed to wow. “You have leech mania coinciding with the rise of the professional pharmacy and the rise of mass advertising, all forces working together to create this full-blown ornate leech jar,” says Diane Wendt, an associate curator of medicine and science at the Smithsonian Institution.

To convince passersby of the quality of their drugs and other treatments, pharmacists stocked their windows with beautiful matched sets of ceramic jars that held things such as tinctures, tamarind, and honey. Leeches—the ultimate jar—was most prominently placed, Jackson writes. The more respectable the pharmacy, the more ornate the leech jar.

From the outside, pharmaceutical leech jars looked just like any other decorative vase except for two distinct details. First: They have a constellation of perforations in the lid for air. Second: They carry the word “LEECHES” in all caps. The jars were generally mass produced by British manufacturers, according to Rachel Anderson, a curatorial assistant at the Smithsonian. The most highly embellished jars came out of Staffordshire, England from Samuel Alcock & Co., whose elegantly filigreed jars are some of the most coveted by modern collectors. Alcock’s jars are also enormous, many exceeding two feet in height. These jars populated pharmacies on both sides of the Atlantic, but held more clout in America, where pharmacies still felt like they had something to prove.

But these fancy, public-facing jars only held a day’s supply of leeches, as Anderson speculates the containers could not have effectively contained the wily creatures for long. Pharmacists kept the rest of their stock out back in a larger holding tank or more utilitarian jars secured with metal clamps or padlocks, Jackson wrote. It’s easy to imagine a carefully curated window display beset by a vector field of escaped, dark brown leeches.

Within the aerated jar, leeches needed constant tending, Jackson wrote. You had to change the water every other day in summer and twice a week in winter, and store the jar away from light. You also had to whisk your leeches, either with a fine willow broom or, in more dire circumstances, your hand. Pharmacists also recommended keeping a layer of pebbles or moss at the bottom of the jar to aid the annelids in their weekly ritual of sloughing their slimy epidermis. Kept under ideal conditions, a two-gallon jar filled a third of the way with water could hold—brace yourself—up to 250 leeches. How pharmacists retrieved the leeches remains a mystery. “We have not come across by happenstance any instrument called a leech tong,” Anderson says.

Fancier jars also implied fancier leeches, which could be an important distinction for health-obsessed Victorians. Not all medicinal leeches were created equal. American leeches, such as specimens from Mississippi or Pennsylvania, were hardly ever used, as they would not latch on unless aroused by the scent of blood and could hold just an eighth of an ounce of blood, according to an 1881 dispatch on leech farming published in Scientific American. Rather, imported leeches from Sweden and Germany were considered the peak of luxury—capable of sucking out two full ounces and supposedly so voracious that they didn’t need bait to bite. In the late 1800s, 100 Swedish leeches sold for $5—the equivalent of nearly $100 today.

In spring and autumn (prime leech season), leech fishers would wade into pools and beat the surface of the water with poles to pull the bottom-dwellers up from the sludge, Jackson wrote. Moments later the worms would begin latching onto legs (or sometimes strips of animal flesh on a stick), to be peeled off for harvest. A good fisher could collect 10 or 12 dozen leeches in a couple of hours.

The process of leeching was rather simple, if time-consuming. The leecher would dry the worm with linen, shave the area that was to be leeched, place the leech in a wine glass, and invert it over the target area. When the creature had drunk its fill, it would simply drop off. Though leeches require several months to digest a proper blood meal, skyrocketing demand led certain pharmacists to reuse the creatures in times of scarcity. “You could get the leech to vomit up its blood dinner by applying salt,” Anderson says. As one might imagine, recycled leeches are a biohazard, and pharmacists recorded many incidents of accidental leech-borne transmission of syphilis and puerperal fever, an infection that follows childbirth.

In the mid-1800s, at the peak of leech mania, inventors sought to improve on the ornamental leech jar. “There were leech aquariums, leech conservatories, specialized larger leech jars that held hundreds and hundreds of leeches on perforated shelves so the leeches could wiggle around the holes and clean themselves,” Anderson says. People also debuted artificial leeches, metal instruments that mimicked a leech’s jaws with tiny blades and a vacuum. According to Anderson, these faux-leeches served one of the same purposes the decorative jars did—to alleviate the “ick factor.”

The Victorian obsession with leechcraft waned at the turn of the 20th century, in part due to unsustainable demand and the growing suspicion that draining vast quantities of a person’s blood wasn’t actually the best way to fix a migraine. Leeches have, of course, seen a therapeutic resurgence over the last few decades, less for the blood they take than for therapeutic compounds in their saliva. But proudly displayed ornate leech jars have yet to appear again in pharmacy windows.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook