The Day Americans Drank Breweries Dry

Eight months before Prohibition officially ended, the country celebrated “New Beer’s Eve.”

Like so many of his peers in the hospitality industry, Paul Lake, the manager of Baltimore’s Rennert Hotel, spent the early weeks of March 1933 glued to his local newspaper stand. In the months leading up to then, reports out of Washington D.C. had suggested politicians were flirting with a repeal of the 18th Amendment. While the wholesale abolishment of Prohibition would take months—if not years—to wriggle its way through the United States Congress, rumor had it legislators were considering a bill that would immediately legalize certain beers and wines. Lake could only imagine how such a law might increase profit margins in his hotel restaurant.

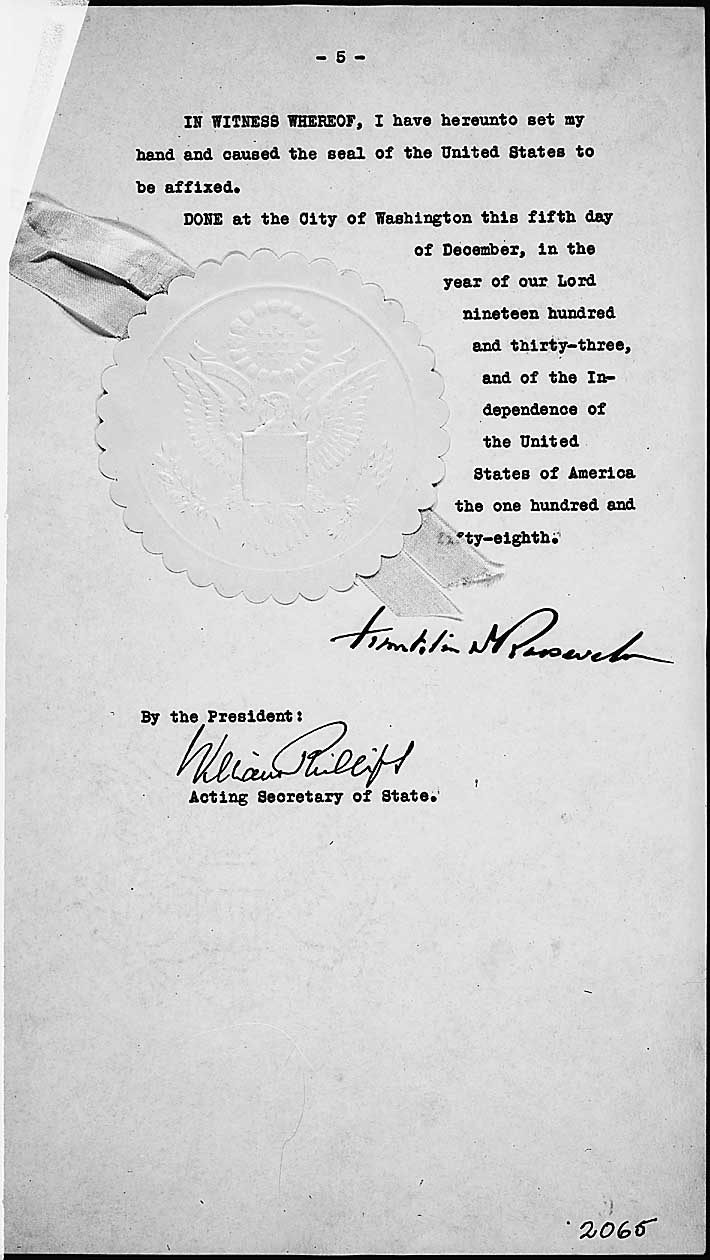

On March 22, 1933, the bill passed. Known as the Cullen-Harrison Act, it only decriminalized beverages below 3.2 percent alcohol by weight. Still, this detracted little from what would later become known unofficially as “New Beer’s Eve.” After 13 long years, alcohol would once again flow in Lake’s hotel starting on April 7, at 12:01 a.m.

Lake didn’t scrimp on pomp and circumstance. To tend bar that night, he re-hired the last two bartenders to work at the Rennert before Prohibition. He installed a brand-new countertop on his bar, and, hoping to attract Baltimore’s press, he shrewdly invited the city’s most famous living writer: H.L. Mencken. Renowned for his polemics against puritanical America, Mencken was also a notorious beer enthusiast. “There is nothing I would like better than to personally hand you the first glass of beer at the reopening,” Lake wrote to Mencken on March 31—to which the writer promptly responded, “Needless to say, I will be delighted.”

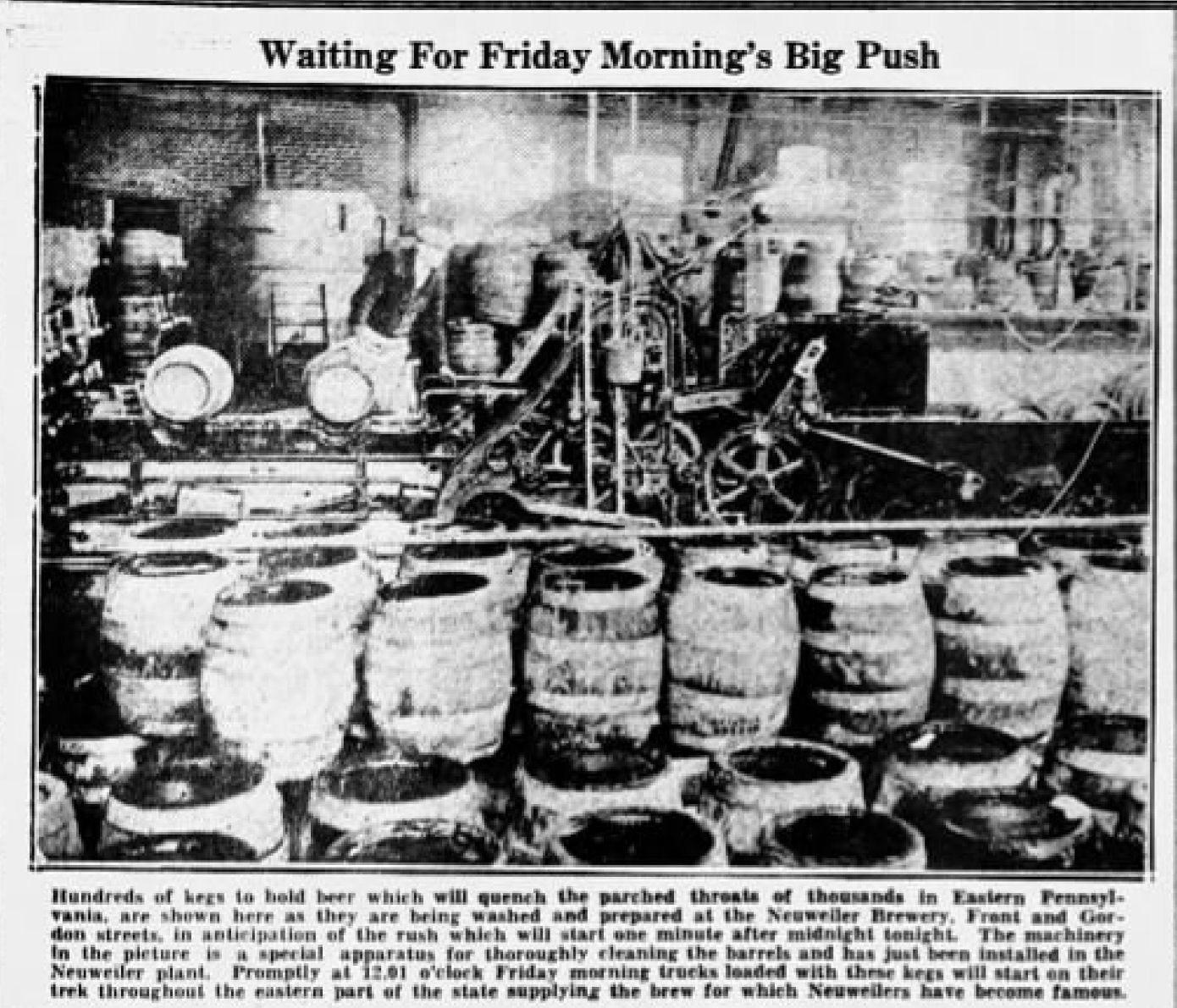

When April 6 finally came, Lake ensured his delivery men were among the first in line at the Baltimore Brewery, which had promised to wheel out kegs at midnight. A hotel employee soon returned with a fresh barrel, and Lake ordered his bartenders to tap the keg. The dense crowd initially groaned as a stream of murky water rushed out. “But presently,” the Baltimore Sun gushed, “the milky brew rushed forth, eager, gurgling, foaming and spattering in its excitement.”

At 12:29, the bartenders passed their first successful pour to Lake, who then handed it to Mencken. The writer accepted it with a smile, cocked his drinking elbow, and took a dramatic pose.

“Here it goes!” he said.

As Mencken downed the beer in two long gulps, the audience silently anticipated his appraisal.

“Pretty good,” Mencken said, still smiling. “Not bad at all.”

As it turns out, Mencken was lying. The beer was actually “sad hog-wash,” he later admitted. Still, for him and other anti-Prohibition provocateurs, the brew’s quality was insignificant. What really mattered was that the scales of public sentiment were finally tipping their way. “America had largely become a beer-drinking country by 1920, when the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act both went into effect,” says historian William Rorabaugh, author of Prohibition: A Concise History. “As far as a majority of Americans were concerned, legal beer was the end of Prohibition.”

Many legislators in the federal government shared this view. Signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on March 22, 1933, the Cullen-Harrison Act came during the peak of the Great Depression. Viewing the 18th Amendment as a roadblock to recovery, the Roosevelt administration had already launched a repeal campaign weeks earlier. In the meantime, it saw the legalization of low-alcohol beer as a dry run for America’s re-acclimatization to public drinking.

Based upon contemporary newspaper reports, constituents in the 19 or so states that had agreed to recognize the Cullen-Harrison Act were more than game to participate in this experiment the weekend of April 7. On what’s now celebrated as the first National Beer Day, throngs of onlookers gathered outside local breweries at midnight. According to the New York Times, revelers across the country navigated sidewalks already packed with newly-licensed hospitality representatives “to watch the lines of trucks waiting for blocks around, see them piled high with cases and kegs of beer at the loading platforms and then adjourn to a nearby restaurant or ‘coffee pot’ and drain a few glasses of brew from the same brewery one had been visiting.”

Outside one unspecified brewery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a Times journalist reported seeing participants carting away beer in “private automobiles, taxicabs, and even baby carriages.” Not to be outdone, “one elderly gentleman with handlebar mustaches came out of the brewery with a tin pail of beer in each hand and made his way to a near-by tenement house amid cheers of the bystanders.”

Similar scenes played out in Los Angeles, Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis. In the latter city, enthusiastic crowds packed outside the Anheuser-Busch plant starting at noon on April 6. After midnight, the same crowds flocked to restaurants and hotels, where live orchestras provided soundtracks to their first public drinks in more than a decade. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, this revelry endured well beyond daybreak. Restaurants brimmed with lunchtime customers looking to complement sandwiches with a frosty brew. As crowds of customers turned over and over, chaos ensued as restaurateurs realized most of their servers had been too young to work at the onset of Prohibition. Many “waitresses struggled to acquire the knack of opening bottles,” the Post-Dispatch reported, and “service men found themselves unskilled in serving beer.”

Confusion reigned on an even larger scale in Salem, Oregon. Though Oregon was indeed one of the states that had agreed to participate in April 7 activities, local breweries and restaurants weren’t completely sure if the government had officially signed off on Cullen-Harrison by midnight. They pushed forward anyway. “Up to noon,” Salem’s Daily Capital Journal reported, “there had been no complaint filed with the city recorder against any local dispenser and at the rate the beverage was disappearing down parched throats it was practically certain that there would be no evidence left by the time the authorities got around to taking action.”

As the Harrisburg Gazette described this mass intake the next morning, “Enough beer went down the hatch in the United States yesterday to float a battleship.” By midday, pride in this accomplishment had already started to wane, as establishments quickly ran through initial provisions. The Times wrote the next morning that restaurants, beer gardens, soda fountains, and other dispensaries “reported in scores of cities that their supplies had been exhausted by early afternoon”—news the Post-Dispatch corroborated beneath what’s now a classic front page headline: “St. Louis Drinks Breweries Dry in Less Than 24 Hours.”

Early estimates for April 7 beer sales sat between an astounding 1 and 1.5 million barrels. The Times reported that taxes on Friday sales alone had racked up $10 million for federal, state, and local governments (roughly $191 million in today’s money). According to Daniel Okrent, author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, one cannot overstate the importance of this haul. “The advent of the Depression and the precipitous collapse of federal revenues meant a replacement source of government income had to be found,” Okrent says. “The tax on legalized alcohol was the obvious one.”

Perhaps more important to politicians, the Cullen-Harrison Act also created thousands of jobs. New York breweries employed 2,000 people in the last two weeks of March alone. In St. Louis, August Busch Jr. told the Post-Dispatch that he had added 1,700 jobs at his brewery in a similar span—this at a time when national unemployment rates exceeded 20 percent. “Bringing back alcohol was a jobs program,” Okrent says. “Brewers, distillers, bottle makers, truck drivers, taverns, liquor stores all needed to staff up. Before Prohibition, the industry as a whole, including all the ancillary businesses, was the sixth largest employer in the U.S.”

The importance of all of this was not lost on Mencken and the raucous crowd at Baltimore’s Rennert Hotel in the early hours of April 7. As the writer roistered with old friends, and unhindered by prohibitory law, he realized the night had taken on added meaning. More than an inconvenience, he had always viewed Prohibition as an affront to personal liberty. In this way, he later told the Boston American, April 7 was more than a quick fix for a struggling economy or a fun night out on the town for old drunkards—it was “an epochal event in the onward march of humanity—perhaps the first time in history that any of the essential liberties of man has been gained without the wholesale emission of blood.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook