The Tea Sommelier Seeking Out China’s Rarest Brews

Shunan Teng is on a mission to preserve and promote legendary teas.

Shunan Teng’s job can be precarious, since she spends a lot of her time hiking the rocky slopes of southern China. On one hike, she gingerly hoists herself into the branches of a camellia sinensis tree in order to inspect the baby leaves. But it’s all in a day’s work for Teng, an avid tea sommelier and entrepreneur.

Teng is on a mission to curate a collection of China’s oldest and most historically acclaimed teas. While the densely packed brush surrounding her looks like a forest, it’s actually a centuries-old plantation of heirloom tea trees, tucked away in the depths of the Chinese countryside.

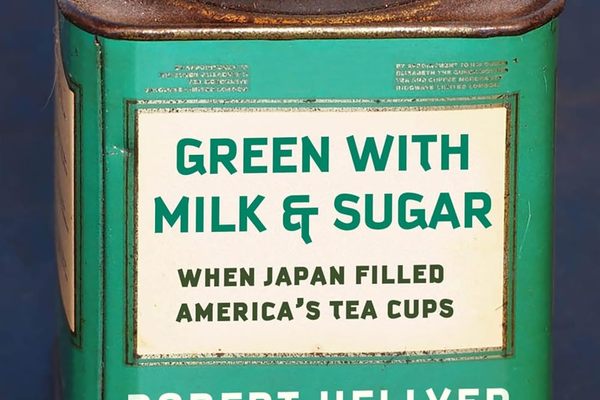

Tea is one of the most commonly consumed beverages in the world. The dried and processed leaves of the camellia plant are versatile enough to star in everything from Tibetan yak butter tea to the perfumed tea lattes of chic cafes. But Teng is a traditionalist, and she wants the teas she sells at Tea Drunk, her New York shop, to come with a pedigree. She travels to China each year to source some of the most illustrious brews from remote, ancient forests.

Teng likens high-grade teas to fine wines, with regions developing their own unique terroir, cultivars, and processing methods. But like many crops, heirloom tea trees are being pushed out by commercial monocultures. In fact, Teng says if it was not for her company commissioning some of these rare teas, they would vanish forever.

Humans haven’t always drank their tea. Instead, people in East Asia originally used tea as a leafy green vegetable or herb. Cultivation is estimated to have begun 6,000 years ago, but it wasn’t until around 1,500 years ago that people began drinking tea as a beverage.

There’s a reason that it took so long for humans to actually start drinking tea. “You can’t just take the tea plant and dry it and call it tea,” says Teng. “There’s a very elaborate and deliberate process that turns this thing from a natural product into the tea we actually consume.”

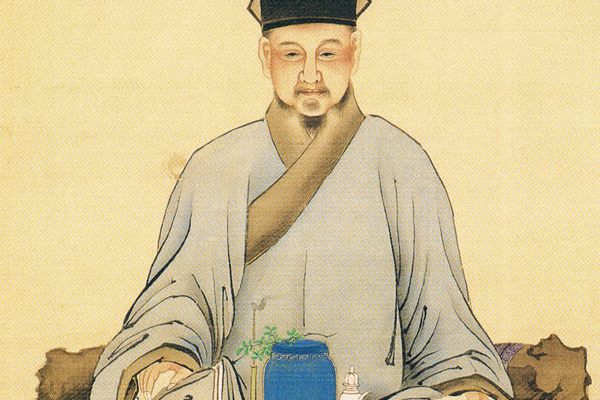

The earliest teas were made by steaming freshly picked leaves in a processing step called “kill green” that prevents oxidation. The leaves were then packed into portable cakes, ground into a powder, and mixed with hot water in a process comparable to today’s matcha. This style of tea became so popular that during the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907) an elite tea culture emerged, and the finest brews were presented as “tribute teas” to the Chinese royal court.

The emperor himself would sometimes weigh in on his favorite teas, giving them a prestigious stamp of approval that would last centuries. “The pure, unadulterated fragrance of a fine tea is greater than all the incense and perfumes in the royal cabinet,” wrote Emperor Song Huizong at the turn of the 11th century. “However, only those tea leaves steamed to perfection, pressed to the right degree to bring out the essences and remove excess moisture, ground and compressed in the same day, will exhibit such excellence.”

Tea connoisseurs also compiled rankings that described the most exceptional brews of the day.“The famous teas are made of the very best each region has to offer,” Emperor Song Huizong also wrote. “For example, one can feel the effort and sacrifice in Taixing rock tea, cultivated on such barren, flat and rocky land; or Qingfeng Suicha which grows on high cliffs, tastes stern; just as one may taste the innocence of Dalan tea.”

The latter Chinese dynasties saw a boom in international trade, and swathes of new tea trees were planted to keep up with the burgeoning demand. “The benefit or advantage of these locations is that they actually left us with very old tea trees,” says Teng. Many heirloom tea groves are now between 200 and 600 years old.

Today, Teng travels across China to visit these historic groves. But in many areas, the dense brush of the ancient tea forests give way to huge homogenous tea farms. It’s a sight that saddens Teng. “Philosophically, we Chinese think that tea trees have a soul,” she says. To Teng, this monoculture of tea bushes is a metaphor for a soullessness begotten by industrialization, especially next to the sprawling majesty of the heirloom trees.

“It’s extra-hard for tea makers to use heirloom tea trees because by nature, they all grow into all kinds of different sizes and shapes,” explains Teng. The unmanicured trees are difficult to harvest, so producers have opted for high-yield, low-maintenance cultivars instead. Some heirloom groves are now under threat, as commercial cultivars compete for the ideal tea-growing real estate.

Teas from the Pu’er region in the south of China, for example, were a popular export in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, but largely fell out of production after the fall of the Chinese empire. Its renewed popularity in the 1990s meant that tea farmers cleared centuries-old groves to make way for cheaper, lower maintenance cultivars. Almost half of the 156 square miles of pu’er groves recorded in 1950 no longer exist.

Many of the elite teas described by scholars in the past have also fallen out of production, as they are incredibly difficult to produce. One of Teng’s rarest, most expensive teas is Jun Shan Yin Zhen, a yellow tea that is only grown on a tiny island in Hunan.“It’s very umami, slightly savory, and it has a really clean, tranquil sweetness in the aftertaste,” says Teng. Farmers have cultivated tea on the island for over 1,300 years, and now, only one man knows the secret of how to make it. Production is extremely finicky, as the tea buds must be picked at precisely the right moment before going through a stringent roasting, sweltering, drying, and sorting process.

Another of Teng’s teas is considered particularly challenging to cultivate. Wu Yi Yan Cha is a type of oolong that grows along the rocky cliffsides of the Wu Yi mountains in northern Fujian. The stunning scenery has earned the area UNESCO World Heritage status, and Wu Yi Yan Chas are known to have a bold taste, floral fragrance, and a mineral mouthfeel that’s often described as evoking “molten stone.”

Teng carries both of these teas and dozens more in her New York shop. The varieties vary wildly, but many share one finicky feature: an ideal harvesting season of 10 to 15 days, giving Teng a very narrow logistical window when it comes to planning her trips to buy them. And to make matters even more challenging, many of the most celebrated tea regions are extremely remote, with difficult terrain.

Teng believes that she is the only one who has gone to such lengths to search for teas across China. While most other vendors will buy teas wholesale from a local market, Teng often camps or stays with the tea makers themselves, for the firsthand assurance that her products are top-tier.

Teng’s professional mission is to see the tea industry enjoy the same prestige as the wine industry. That’s why to her, preserving historic teas is tantamount. “I believe these traditional teas hold the pinnacle of the industry,” she says, and her greatest fear is losing any of them to oblivion. But beyond history or business, her work has left a deep impression on her sense of self. Wandering the tea forests of China, she says, “has made me, in a way, more Chinese. That’s something that’s enriched my life so much.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook