The Women Who Ran Genghis Khan’s Empire

From fighting in the army to managing the kingdom, women were key players in every aspect of the Mongol Empire.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

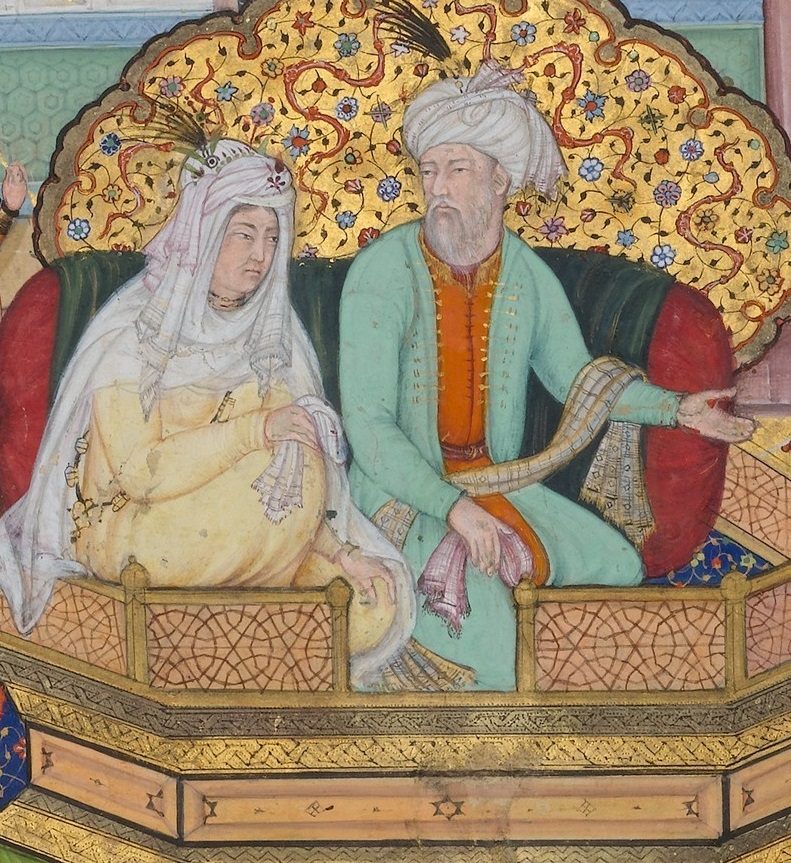

In 1178, a 17-year-old Mongol woman married a man she hardly knew. And while her husband traveled and fought and conquered, she ruled those who remained in Mongolia, managing every aspect of daily life in a massive nomadic camp. Commanders and shepherds alike reported to her, and she coordinated complex seasonal migrations of thousands of people and their livestock. At 28, she became the Grand Empress of the Mongol Empire; her name was Börte.

Börte’s husband, Chinggis Khan (also known, based on the Arabic transliteration, as Genghis Khan), receives all the glory for founding the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever known, but Börte and her immense contributions have been largely forgotten. While their husbands fought in distant, years-long military campaigns, Börte and other Mongol women kept the empire running. Some women also rode to war. Khutulun, Chinggis Khan’s great-great-granddaughter, would swoop down on the enemy “as deftly as a hawk,” wrote Marco Polo.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Central Asia scholar Anne Broadbridge, author of Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire, about the many roles women had in the Mongol Empire, how society perceived them, and the rise of perhaps the most powerful woman of the medieval world: Töregene.

What were the responsibilities and tasks of the Mongol women in charge of camps?

The better question would be what weren’t their tasks. I think we could put it all in the general category of management. [For example,] Chinggis Khan’s senior wife, Börte, is responsible for a camp. She’s responsible for their home, the yurt or ger that they live in. She’s responsible for the kids. If merchants come through, she’s going to talk to them about economic activity. She is going to oversee or perform the typical daily herding activities. There’s food preparation. There’s clothing preparation. There are religious rituals. There’s entertainment. It’s often a woman’s job to be the hospitable partner, to bring in food and welcome guests. And then there’s all the thousand and one little things that everyone does every day—mending things, checking in with people, checking on kids, making sure that the kids aren’t fighting too much, etc.

Furthermore, when the camp had to move from point A to point B, which it did regularly according to season and pasture, women were in charge of that. They organized the procession of carts. They’d drive that long line of carts, often drawn by oxen or yaks. When they arrived, they would place the yurts in the correct order, set them up, etc. So without women running the place where Mongols lived, there wouldn’t have been a camp for the Mongol men to return to from their military campaigns.

After Chinggis Khan’s death in 1227, many women rose to power. Why?

Succession is very complicated. But women can take over, in theory temporarily but sometimes not really temporarily, on behalf of some man, usually a son of their own.

So in the case of Töregene, who became regent of the entire Mongol Empire after the death of Chinggis Khan’s son Ögedei, or in the case of Sorghaghtani, who maneuvered her son to be the ruler of the entire empire, they’re functioning as senior widows who are regents for men. That’s perfectly acceptable in (their) nomadic society.

How did Töregene become regent of all Mongolia, around the year 1241?

She had remarkable skills. She enters the family in a very disadvantageous position. Chinggis Khan’s army kills her husband and she becomes a trophy wife for the third son of Chinggis Khan and Börte, Ögedei, who succeeds his father as overall Great Khan. Töregene isn’t even the senior wife (but) she produces five living sons. The senior wife produced no children. So sort of by default Töregene rises up. By the time Ögedei himself died, she was in a position to take over as the actual senior wife. So she wrote to all of the senior members of the family when her husband died and said, “Oh my goodness. We have this situation. What shall I do?” They wrote back and said you should be regent until we can get together and decide who will be the next ruler. So she worked the system very well in her own favor.

Ögedei, her dead husband, had a preference for who should be the next Great Khan. Töregene had a different preference. She wanted her oldest son to be Khan. And so at this big general assembly that she called and hosted and paid for, she managed to lobby successfully for her son to take over—even though this was in opposition to her dead husband’s express will.

What was Mongol society’s perception of these powerful women?

We don’t have much [historical material from the Mongols], but what we do have implies acceptance. This is the way things are. Women have authority. They do certain things. You check in with them. You ask their advice. You listen to them when they speak. This is normal. So although outside observers see the amount of authority that some women have in these societies as unusual, for people living in those societies it was normal.

Did Mongol women fight in armies?

[Historians] have indeed found evidence that more than we thought of the Mongol armed forces were, in fact, women—maybe as much as 20 percent. We’re not talking half, but they were there.

What would you like the world to know about Mongol women?

I want people to know how much they mattered. They’re half the story at least. Without Mongol women, there would have been no Mongol conquest, no Mongol empire. There would have been nothing. In Mongol society, you have something like 90 percent of men able to mobilize and engage in warfare. No other contemporary society—not medieval China, not medieval Iran, not medieval Europe—can do that, because men have to do other jobs. They have to be priests, farmers, administrators. In Mongol society, women do all of that stuff. So without women behind the scenes running everything else, men would not have gone anywhere.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook