The Forgotten Women Who Ruled the Medieval Middle East

A new book tells the tales of the queens of Jerusalem.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

Damascus wasn’t in good shape in 1132. Assassins had just killed the king. The new king, Isma’il, was paranoid, greedy, and prone to violence—even brutally executing his own half-brother. Then, in a move that violates kingship’s most basic tenets, Isma’il planned to give Damascus away to the enemy. Enter Khatun Zumurrud, Isma’il’s mother. She was not about to let that happen. In 1135, she had her own son assassinated and his body dragged through the streets.

Zumurrud wasn’t the only woman you didn’t want to mess with in the medieval Middle East. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Christian Crusader State founded by Europeans in 1099, saw two queens during this period, Melisende and her granddaughter Sibylla, whose political machinations, affairs, and rebellions could rival those of Game of Thrones. There was also Theodora of Jerusalem, the widowed queen who ran away to the Islamic world with the man she loved (who also happened to be her father’s cousin), Alice of Antioch, who twice tried to take the throne, and more.

Atlas Obscura talked to Katherine Pangonis, whose new book, Queens of Jerusalem: The Women Who Dared to Rule, explores the complicated lives and legacy of the forgotten women who ruled the medieval Middle East.

What was the role of women in the medieval European world? In the Crusader State of Jerusalem?

At this time, women are very much second-class citizens. They have limited rights in terms of inheritance, owning property, their marriages. Women aren’t meant to be in power unless they’re protecting their husband’s land or his interests. So that’s one of the places in which it’s acceptable for a woman to have power and that’s the same in Europe as it is in the Middle East.

What I found quite interesting was that the unique instability and this constant state of crisis in Outremer [another name for the Crusader States] gave women more opportunities to not just inherit power, but also to wield it.

Does there have to be instability to upend the patriarchal structure?

That’s generally a key part of women getting power. Basically, for women to take power, there has to be a shortage of suitable men—either sons aren’t being born or kings and heirs are dying.

So if you look at the example of Matilda of England. She’s an English queen who, in theory, would become one of the first queens regnant. Her father, Henry I, has a son and heir, but then his son is killed in the wreck of the White Ship. And he names Matilda heir and she’s a direct contemporary of Melisende [of Jerusalem]. So it’s a great comparison because Melisende is going through something similar in the Middle East.

The difference is that in the Middle East, there isn’t the possibility of having a succession crisis because the Crusader States are so fragile. They’re in danger all the time. They can’t afford a civil war of the sort that England then has over whether or not Matilde should inherit, a civil war that lasts well over a decade.

Tell us more about Queen Melisende of Jerusalem. How did she come to power?

Melisende is the daughter of Baldwin II, the third king of Jerusalem. And Baldwin has four daughters and no sons, and he makes it clear from quite early that Melisende’s the heiress to Jerusalem. Then she’s married to a suitable man, a guy called Fulk of Anjou. And Fulk is 100% expecting to be named the sole heir to the kingdom. However, on Baldwin’s deathbed, he changes the rules. And he says, in fact, I’m leaving my kingdom in three parts to Melisende, Fulk, and their baby son, which is obviously infuriating to Fulk.

Then there’s this major scandal that erupts very shortly after they come to power—someone accuses Melisende’s cousin, the Count Hugh of Jaffa, of treason and challenges him to trial by combat. There’s a rumor that Melisende was having an affair with her cousin. And then this plunges the Kingdom of Jerusalem into what is tantamount to a civil war. Hugh rebels and allies with the Egyptians of Ascalon and tries to fight Fulk and is defeated. After that, Hugh is sentenced to exile. And while he waited to be exiled, there’s an assassination attempt made in his life. He gets stabbed very badly and then dies there shortly after.

Melisende at this point loses her temper. She’s just is so furious about Hugh’s death and about being dragged into this scandal that she suddenly really comes into her own and starts asserting her authority. Fulk is genuinely terrified of her. And from that moment forward, Melisende’s name is on charters. We start to see her influence in making donations to various causes, such as the military orders, the Church, and then—Fulk dies! This leaves Melisende as regent for her son because he’s too young to rule.

And what’s even more remarkable is that even once her son comes of age, Melisende keeps ruling and doesn’t surrender power to him. Eventually she goes to war with her son over who should rule the kingdom. And even when she’s defeated, she’s not really excluded from politics. She just has to take a step back. She was a very powerful woman with a very magnetic personality who had been very clever in building up serious alliances in her kingdom.

What’s the legacy of the Crusader States and the women who ruled them?

It’s a hard question because the Crusades were very bad. There’s mass genocide and it’s proto-colonialism. It’s a very thorny topic. So, I mean, a hugely negative legacy, to be honest with you.

When it comes to the women of the Crusader States, I think Melisende’s rule did influence the roles women play in medieval Europe. They saw women commanding in the Middle East, and that strengthened the case for women to have more power back home.

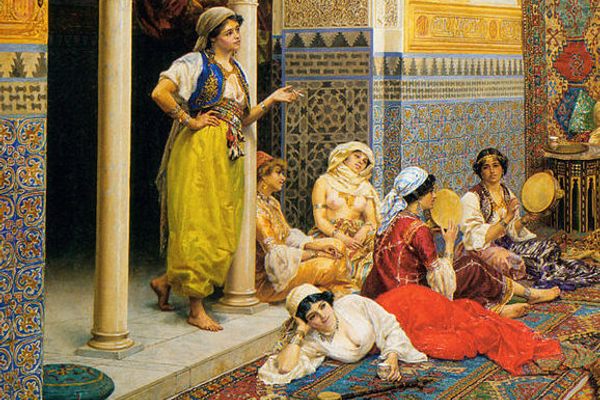

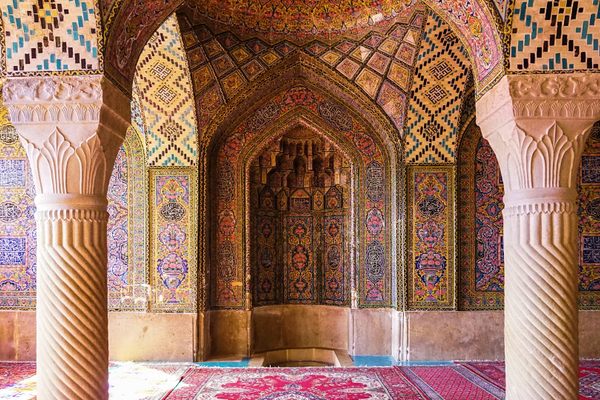

I also think it’s very important to know that women were wielding power on both sides, both Christian and Islamic. That’s often not what people expect. People often think of medieval princesses sitting alone in towers. If they think of Islamic princesses, they think of women in harems not able to go outside or be educated. But we know Saladin’s wife [Ismat ad-Din Khatun, who in 1176 married Saladin, the Muslim sultan who took back Jerusalem from the crusaders in 1187] is writing letters to him on an almost daily basis and was commanding negotiations and sieges. The myths aren’t always true.

Why have these women been overlooked?

Because the chronicles are written by men. And they’re pretty much always written by churchmen as well and obviously, in medieval times, churchmen aren’t having a lot of experiences and interactions with women. So there’s just a lot of discomfort about including the deeds of women in the chronicles because they’re not considered to have the same power and importance as men. The chronicles often attribute things done by women to men.

And then that, in turn, influences how much modern historians write about women because if there’s less source material, it’s much harder to focus on them because there’s less evidence for what they did. So the project of my book really was going through and collecting all the evidence for the deeds of these women and trying to string it together in a compelling and accurate way.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook