How a 16th-Century Spanish Questionnaire Inspired Indigenous Mapmakers of Mexico

Bureaucratic paperwork led to pretty maps that highlight power structures and visual identity.

In the 1980s, Barbara Mundy journeyed all the way to Spain to track down more than two dozen 16th-century maps of Mexico. But she quickly learned that not everyone treated them with the same reverence that she did. Mundy, now a professor of art history at Fordham University specializing in Latin American art, would show up at archives, hand over her credentials, and wait for the materials to be hauled from storage. When they arrived, they were often folded into little parcels and haphazardly stuffed into volumes. Sometimes, staff would pass them to her with a lit cigarette in hand.

That relaxed attitude toward the documents took Mundy by surprise. The rough, gruff approach wasn’t universal at the time, and would be nearly unheard of today, when centuries-old materials are usually handled much more gingerly. To Mundy, the maps were precious, and called for a gentle touch. “They show us this horizon of mapmaking in the New World, the way that indigenous people are reimagining their landscape,” she says. “They’re so important.”

Long before Mundy sought them out, these art objects—richly colored, ornately detailed, and mightily compelling—began their lives as administrative paperwork. The painted landscapes, 19 of which are currently on display in the exhibition “Mapping Memory: Space and History in 16th-Century Mexico,” at the University of Texas at Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art, were an arm of the relaciones geográficas (“geographic relations”) effort—an undertaking nudged along in the 1580s because King Philip II of Spain found himself at the helm of a sprawling land, taken by force, that he knew very little about.

“The Spanish king had no idea what his territory looked like,” Mundy says. He hadn’t been there, and a transatlantic voyage was no small undertaking. What the government could do, instead, was issue a 50-question survey.

A few generations after Spanish troops and their indigenous allies seized the Americas, administrators fanned out across New Spain. They distributed surveys and convened groups of residents to provide a lay of the land. “The questionnaire asked for many things—the history of the town, when it was founded, who was the conquerer,” says Rosario I. Granados, the Blanton curator who organized the exhibition. The surveys asked for a tally of the characteristics of the natural world, and the way humans harnessed or exploited them—the nearby volcanoes and lagoons, the fruiting trees and fruitful quarries, the location of ports and the ferocity of the sea, the illnesses that felled communities and the remedies residents used to stall them.

Some returned answers spanning five pages, or even 30; others, Mundy says, were nearly book-length manuscripts. The responses, Granados says, were “really a compilation of information that transcended what we now understand as geography.”

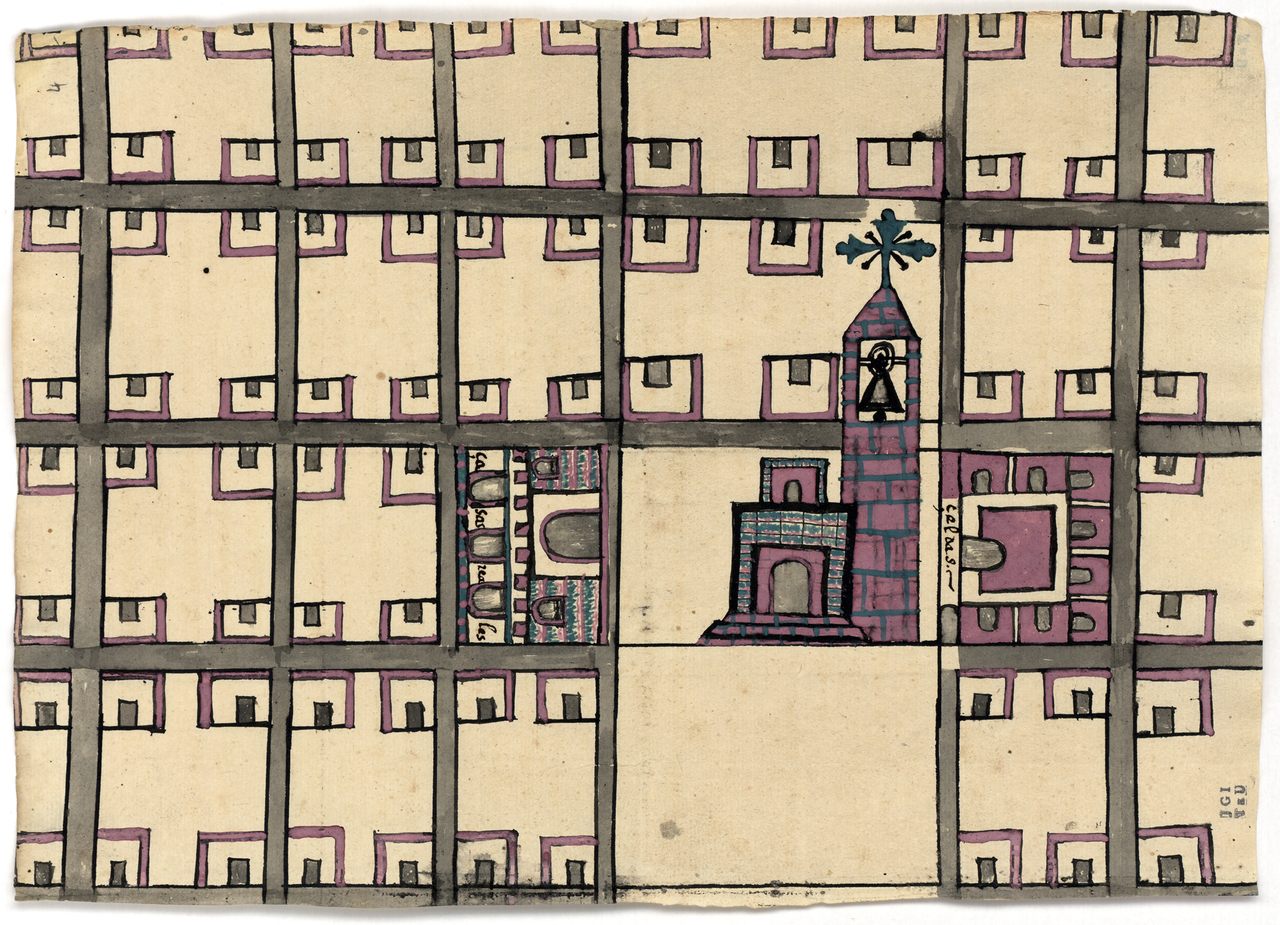

The maps are responses to survey question 10, which asked for a visual representation of the town. Respondents were simply told to make a pintura, or “painting.” It was an elastic term, and artists interpreted it in several ways. Some returned tidy street grids, while others set their sights on mountain ranges, and others focused less on a static landscape and more on depicting change over time. Several maps feature inscriptions in multiple languages, including Nahuatl and Spanish. What they have in common is a snapshot of how some members of indigenous communities saw their home at a time of tremendous change.

“Through the iconography, we can pretty securely determine that most of these are [made by] indigenous artists,” Mundy says. The visual language includes elements of Aztec maps, such as footprints and water denoted by vibrant Maya blue pigment, with swirling shapes that emphasize the dynamism of eddies and currents. All of this leads scholars to believe “these are not Spaniards coming in and making these maps,” Mundy says, though Spanish authorities were present for the process. Towns that already had a rich mapmaking tradition “created in the way they knew,” Granados says.

Even so, the pictures only illustrate the experiences of a small sliver of the population. Though most of the mapmakers are unknown to us, it’s safe to say that they were all made by powerful, privileged members of indigenous communities. “We know from other historical documentation that people who would have been painters were always elites, because painting was not just a mechanical art—it was a way of making knowledge visible,” Mundy says. It was an esoteric and vaunted enterprise. “The painters of these, because of their special skills, would have had elevated status in the native communities,” Mundy says, “no matter what ethnic identity they had.”

These paintings depict tangible structures like churches and waterways, but they also say something about the underlying power structure. The map of Iztapalapa, for instance, includes a roomy community center where the elites would have gathered—and the artist depicted it even larger than the church. Granados believes that these kinds of artistic choices reflect social stratification. “The hierarchies that were very much alive when the Spaniards conquered continued to be alive two or three generations after,” she says. Conquest shuffled the strata a bit, but it didn’t upend it. “Instead of having them at the top of the chain, you have a Spanish ruler on top.”

Even as they emphasized their native cultures, the artists employed some of the cartographic traditions emerging in Europe. The map of Culhuacán, for instance, shows a cluster of hills grouped together, the way European mapmakers rendered topography, which departed from a tradition of depicting mountains as discrete, bell-shaped mounds. That symbol does endure on other maps, such as the one of Tetliztaca—but that map is transatlantic in other ways. On that pintura, footprints wander past a church depicted in the European style. “You see how the two visual traditions are mingling in one single document,” Granados says. The maps feature various riffs on a standardized church symbol: a simple, boxy rendering crowned by a cross and a bell tower, and often bearing virtually no resemblance to the actual structure on the ground. Mundy suspects that the painters may have been familiar with these representations from Spanish coins or books—or, more rarely, may have encountered them on “printed [European] city plans, where a little castle and a gathering of buildings signify a city.”

As much as the empire was forged through force, it was also propped up by paper, and the surveys eventually sailed back to Spain. As for exactly who laid eyes on them—that’s a little murky. “Unfortunately, we don’t have any record of what [the King] thought when he saw the maps,” Granados says. “It could be that he never actually saw them.” It seems that his cosmographer, Juan López de Velasco, did. The maps entered Velasco’s files and were later archived before about 35 of them were sold to the Mexican collector Joaquín García Icazbalceta in 1853. Icazbalceta’s heirs offloaded them in a sale decades later; they arrived at the University of Texas at Austin in 1937.

Whoever eyed the finished products in Spain, Granados adds, “we can imagine that these maps were not exactly what they were expecting.” They describe human experiences of the space, beyond the bald facts of longitude, latitude, and they drill down into specifics about resources prime for extraction. None seem to serve the goal of creating a giant, precise map of New Spain geography. Granados will display the maps, which are in the LILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections at the University of Texas at Austin, alongside contemporary art and discussions about “the flexibility of borders, how identity is mixed, how different groups live together, and how power has to be negotiated to some extent.”

A map is an exercise of power: evidence of someone studying a landscape, wrangling it, and trying to organize it into something sensical to them. “Making a map is a way of controlling that territory and creating it in your own imagination,” Granados says. “It’s something you can share with others and say, ‘This is what I have done.’” These maps may have been intended as useful trophies for Spanish officials—proof of the spoils of land, and keys to leveraging them—but today, Granados and Mundy view them as something more complex. “I love that these maps force us to understand how nuanced the process of inculturation was,” Granados says. They’re evidence, laid down in pigment on paper, bark paper, or deerskin, that conquest didn’t snuff out the vibrant visual culture that had flourished before.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook