Sold: A Black Texan Trailblazer’s ‘Treasure Chest’ of Recipes

Lucille Bishop Smith’s famous recipe boxes are still sought after.

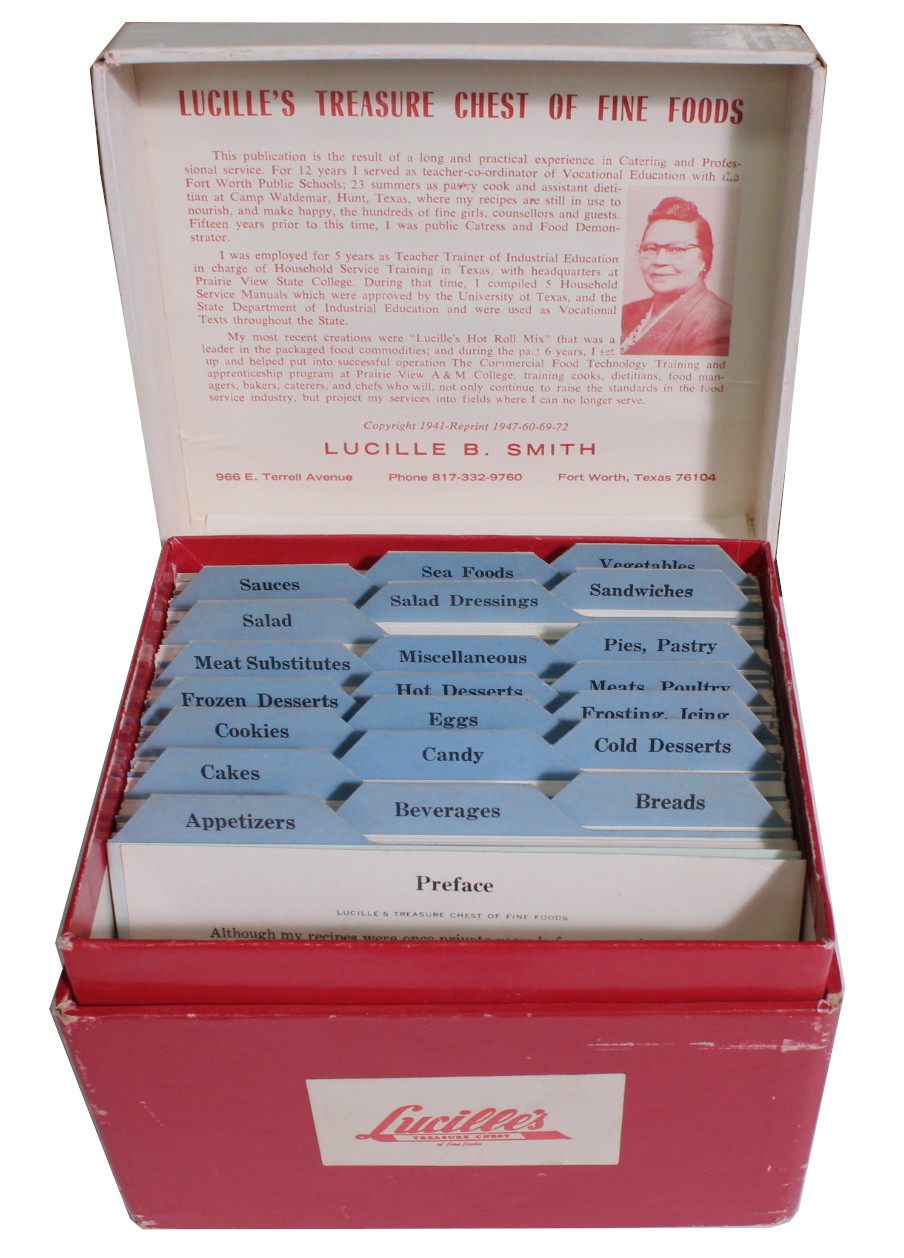

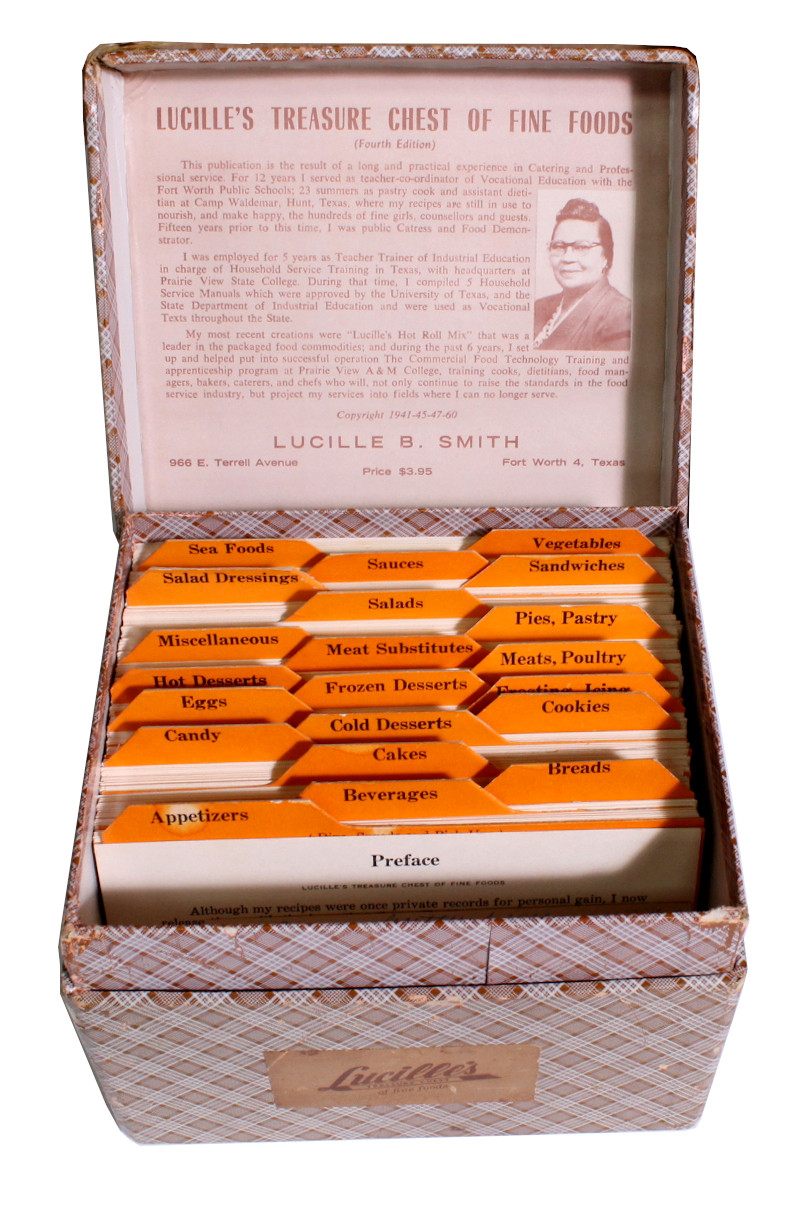

A compact cardboard box full of recipes on index cards was a hot item at a virtual rare book fair earlier this month, selling for $1,650. But this wasn’t your average recipe box. Instead, Lucille’s Treasure Chest of Fine Foods was the work of Lucille Bishop Smith, a trailblazing Black chef, educator, and entrepreneur whose legacy lives on, at both a Houston restaurant named for her and in her sought-after collection of recipes.

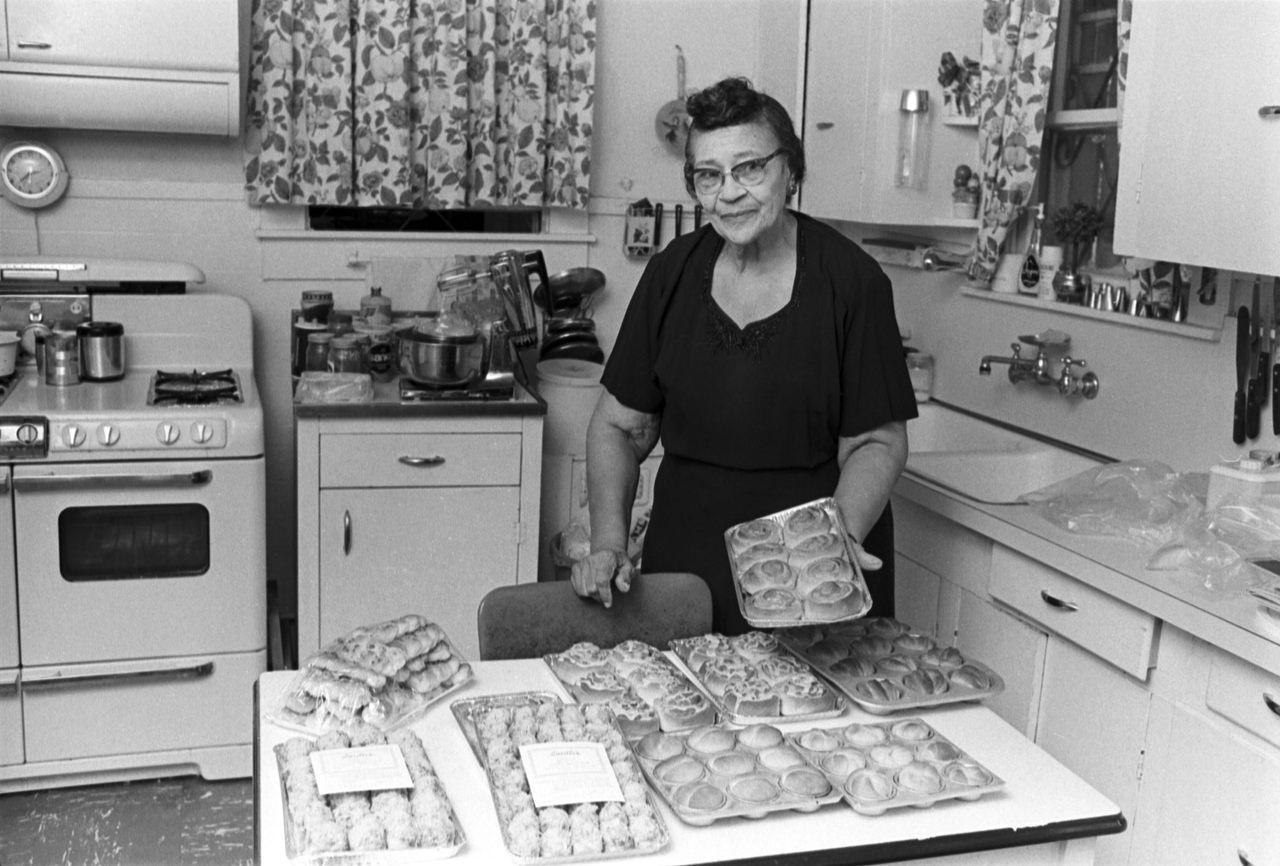

Smith was born in Crockett, Texas, in 1892. She parlayed years of schooling into a career in education, teaching students through Fort Worth Public School District’s vocational education program. While working at Camp Waldemar, she met her husband, Ulysses Samuel Smith, the “Barbecue King of the Southwest.” Between them, they cooked for decades for the campers. She also wrote household service manuals and instituted a training program for food service industry workers at Prairie View A&M College. She is often credited as Texas’s first African-American businesswoman, eventually founding and incorporating Lucille B. Smith’s Fine Foods, Inc. in 1974.

But long before, in 1941, Smith published a cookbook in the form of a box of recipes. Lucille’s Treasure Chest of Fine Foods includes more than 400 cards, from Appetizers to Vegetables, and features Southern favorites such as hush puppies, spoon bread, and hominy casserole. Less familiar dishes, such as banana flake salad and potato fudge, also make an appearance in at least one of the following editions, of which there were many. Smith’s recipes proved successful enough to reprint in 1945, 1947, 1960, 1969, and 1972, although the extent to which they changed or evolved is, as yet, unstudied.

Which may be why not one but two Texas institutions tried to acquire the 1972 edition that Adam Schachter of Houston’s Langdon Manor Books listed for sale last month. Within hours, the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries had purchased it. For a second buyer, the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Schachter dug into his stock, coming up with a 1960 edition for them to purchase.

Brenda S. McClurkin, head of special collections at the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, explains that her department had already researched Smith. So when she spotted the recipe box on offer, “I instantly knew what it was, who she was, and what an important role she played in Fort Worth and Texas history.” McClurkin says she envisions the object being “a regular part of our instruction on African American history.”

Russell L. Martin III, director of the DeGolyer Library, has been actively acquiring cookbooks for 15 years. But he’d never seen a Treasure Chest until now. “It fits perfectly within our cookbook collection,” Martin says, one that he notes is especially rich in Texan and western cookbooks. “Cookbooks can be approached from so many different angles: social history, publishing history, women’s history, local history, business history. Not to mention culinary history,” he says. “They really are mirrors of the age, and help us to see our cultural life in a unique perspective.”

A worthy project would be to secure copies of all the editions and track how they changed over the years, but the boxes are “institutionally scarce,” according to Schachter. A WorldCat search of holdings in libraries turns up only one, a 1960 edition at the Texas Women’s University Library in Denton, but scholar Rebecca Sharpless reports that the Fort Worth Public Library has one as well. It’s possible that the challenge of cataloguing a cookbook-in-a-box may be obscuring other extant copies.

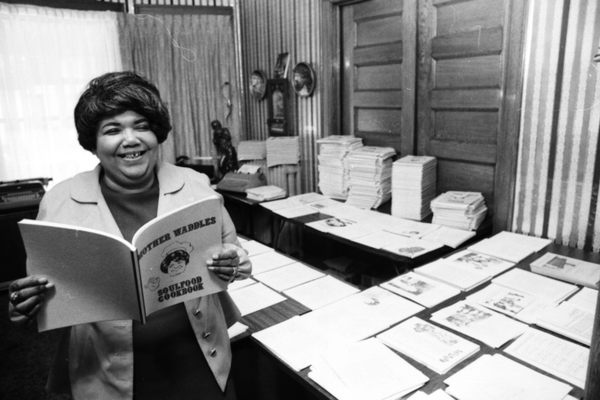

Still, its collectability appears to be on the rise. Toni Tipton-Martin, who brought Smith to wider attention in her 2015 book, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, owns a Treasure Chest and keeps it “under lock and key in a fireproof safe,” she writes on her blog. Several of her readers have chimed in over the past nine years, either to ask where to buy one or to announce an eBay listing. For some, the appeal is nostalgic—recalling, for example, the delicious fare served at Camp Waldemar. But others are drawn by another facet to Smith’s story. Tipton-Martin points out that Smith not only coached “young African American cooks toward culinary proficiency” but also wanted to “empower others by using food as a tool of social uplift.”

Smith led by example. In 1965, during the Vietnam War, she baked Christmas fruitcakes for every service member from her county. She raised funds for church and civic service projects; notably, her famous hot roll mix was developed in the mid-1940s as a benefit for her church and went on to become the first commercially packaged mix for instant dinner rolls. Smith’s rolls are still on the menu at Lucille’s, the Houston restaurant owned by her great-grandson, the chef Chris Williams.

Smith’s history of civic engagement also continues at her namesake restaurant. When Williams was recently interviewed by CBS This Morning about donating meals during the pandemic, he said,“When stuff goes bad, that’s when we step up, that’s when we stand up. We look for these opportunities … that’s the core of our business here. It’s about service, as it was for my great-grandmother, as it is for my family, period.”

Then, on June 8, another opportunity arose. Lucille’s hosted George Floyd’s family and former Vice President Joe Biden in a private dining room that doubles as a shrine to Smith. In the room, another one of her Treasure Chests sits, permanently on prominent display.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook