How Street Artists Honor George Floyd and Magnify a Movement

Muralists across the country are painting new visions of Black liberation.

As racial justice protests continue to erupt in cities across the world, prompted by the killings of George Floyd and many other Black Americans, so too has another phenomenon: the proliferation of murals honoring their lives and critiquing systemic oppression. The murals are united in their themes, but artists everywhere are adding their own unique spin.

#CreativesAfterCurfew

Minneapolis, Minnesota

The artist Leslie Barlow lives just a few blocks away from the Cup Foods where a police officer killed George Floyd. “It just wasn’t something I could escape from,” Barlow says. “Even if I wanted to.”

So she didn’t. Minneapolis is home to a thriving arts scene where artists of color, like Barlow, are in constant communication with each other. After Floyd’s death, she and an artistic collaborator, Olivia Levins Holden, joined #CreativesAfterCurfew, a collective of artists of color who meet up in different parts of the city to paint murals together. “Artists have a really important part to play in this movement,” Levins Holden says. “We’re helping with the narratives that are taking root.”

Their system is chaotic, but there’s a method to the madness. Over 40 artists are part of a group chat on Signal, the encrypted messaging app. They are split into muralists and organizers, who help with planning and sourcing art supplies. Each mural is centered around a sketch or design that an artist has created, Levins Holden explains. Once it’s been sketched out with thinned-out paint or chalk, different artists will fill in different sections of the mural, understanding that the goal is speed, and not always perfection.

The process can take anywhere from six to 30 hours, over the course of one to three days, before an artwork is complete. But in just a few weeks, murals from #CreativesAfterCurfew went up all over Minneapolis. And while the hashtag is being used on social media to identify each piece, the art never includes a signature. “The focus isn’t on us as artists, it’s not about our own personal platforms,” Barlow says. “This is about a community, and the work we’re doing from the ground up to push that message forward.”

Robert Upham

Olympia, Washington

A few days after the death of Floyd, Robert Upham figured out what he could do in response. When the building where he rented office space began boarding up its windows, Upham arrived with spray paint, stencils, and a vision. Over the course of several days, Upham began a 90-foot mural on plywood that was used to surround the building, which sits across from the Capitol Theater on Fifth Avenue in downtown Olympia.

Upham’s art is rooted in his culture as an American Indian of primarily Dakota Sioux and Salish Indian descent. Next to portraits of Floyd and Breonna Taylor, he painted John T. Williams and Sitting Bull, Native Americans who were killed during encounters with the police. He also included other important motifs from Native American history, such as stencils of salmon that allude to the fish wars.

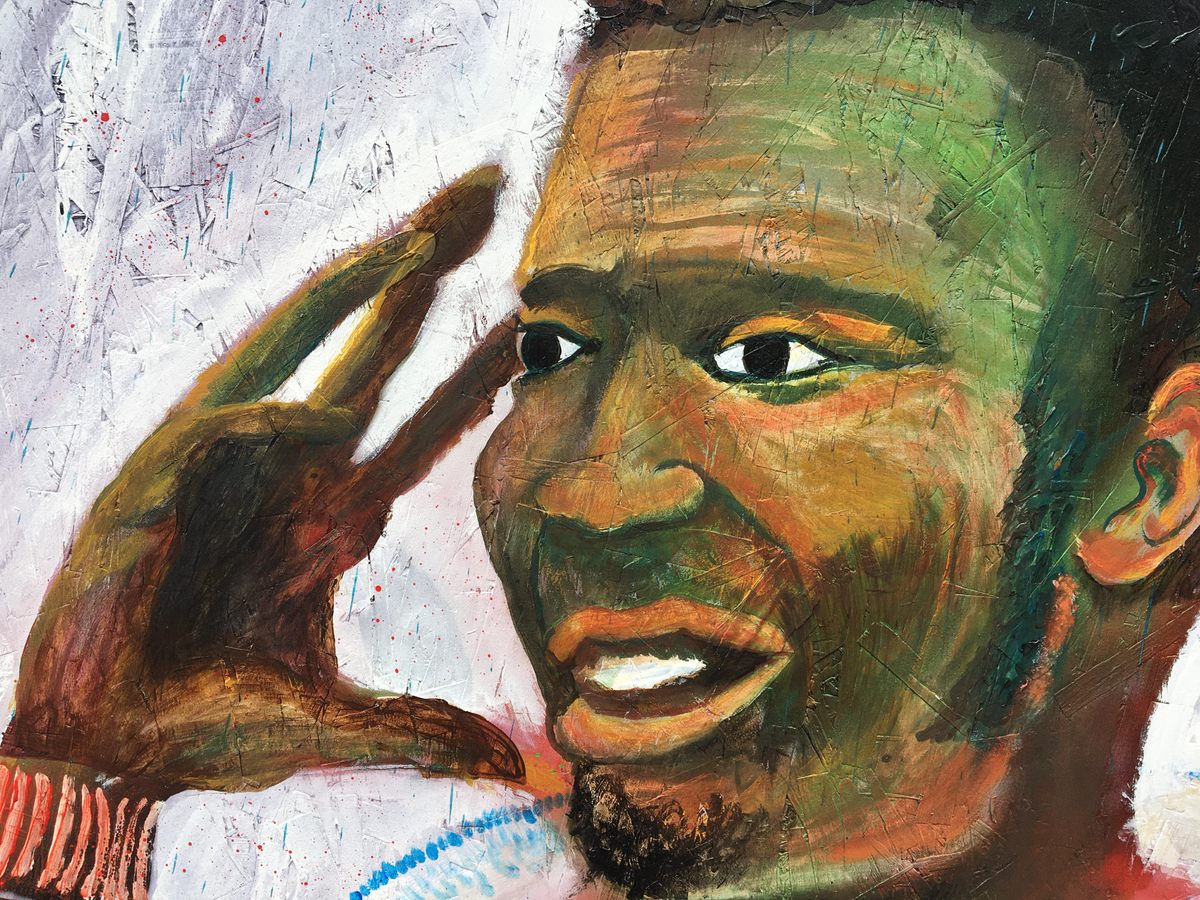

The design of the mural is Upham’s, but fellow artists Ayda Rose and Vincent Li were also key collaborators. Rose provided the stencil of Floyd, while Li contributed portraits of individuals who have been killed by police, including Trayvon Martin. Other volunteer artists use a combination of spray and acrylic paint to complete the mural, adding yellow and red hues to Floyd’s face and a colorful tint to his eyes.

Upham says he’s spent over 128 hours on the mural in the past week. Often, Upham will begin each morning alone before volunteer artists join him later on in the afternoon or evening. “It’s not even done yet—it’s a process,” Upham says. “I’ll still be working on it until they tell me to take it down.”

Jules Muck

Greater Los Angeles, California

Since June 1, Jules Muck has single handedly completed over 30 paintings of Floyd around greater Los Angeles—and she’s still going. It all started when some of Muck’s friends began closing their stores in anticipation of protests. They reached out to Muck to spray paint murals on their boarded-up windows and doors, as a show of solidarity. “I’m moving really fast,” Muck says. “Floyd has incredibly strong features, his face is very recognizable. It looks like him right away, within seconds of sketching, you can tell who he is.”

Muck has painted portraits of Floyd, Taylor, Ahamaud Arbery, as well as other Black victims of police brutality such as Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, and Michael Stewart. After priming with generic house paint, Muck outlines the figure and uses artist-grade spray paint to complete the project. In a few hours, she’s done with each one.

Muck isn’t making money off this work. Instead, she’s asking the store owners to send her receipts from donations to bail funds. Since COVID-19 has made it difficult to acquire supplies from stores, she’s also accepting donations of art supplies to help with her project. “I just hope that the murals bring comfort to both the victims and their families,” Muck said. “I hope they know that they’re being heard. Every shop owner I’ve painted for is on their side.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook