The Poetry-Loving Cook Who Fed Detroit’s Soul

With a 35-cent-meal restaurant and other charities, Mother Waddles was “a one-woman war on poverty.”

In the sweltering summer of 1967, Detroit had reached a breaking point. Heightened racial tensions, socioeconomic disparities, and growing allegations of police misconduct culminated to create a city on the brink of chaos. The ensuing riots would last five days, riddling the streets of Detroit with terror and violence: 43 people killed, 7,000 people arrested, and more than 5,000 residents left homeless by the destruction. Most businesses had been instructed to shut down and vehicles were cautioned to stay off the road. Most, however, were not Charleszetta “Mother” Waddles.

When very few individuals and organizations were braving the streets amidst the calamity, vans from the Mother Waddles Perpetual Mission were distributing food and clothes to those in need. The events of July 1967 would go on to spark a movement of increased activism and political engagement among the Black community in Detroit. Some credit is due to Mother Waddles for ensuring this movement stayed fed.

Although Mother Waddles wore many hats—reverend, mother, businesswoman—food was always at the heart of her work. When she opened the Helping Hand Restaurant on the edge of Detroit’s Skid Row in 1950, her mission was to provide meals for all those who walked through the door regardless of race, creed, or class. In turn, she developed one of Detroit’s most respected and revered community food programs.

Charleszetta Waddles was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1912. After her father died and her mother was rendered bedridden by congenital heart disease, 12-year-old Charleszetta left school to support her family. In addition to working as a housemaid, she also started learning how to provide for her loved ones in the kitchen. “I remember, the first thing I ever cooked was spaghetti,” she recalled. “I carried it to the bed and let [my mother] look at it, and tell me the next step and I’d go back and fix it and carry it back to her bed, and let her look at it.”

After relocating to Detroit as an adult, Waddles started on her path toward serving her community. A single mother of 10, she bonded with other working-class Black women, forming a prayer group that would cook for one another and for those in need. “I’ve put tubs in front of my house on weekends and sold barbecue,” she told Vern E. Smith of Newsweek, as a means to raise money for her local church. In the 1950s, after being ordained as a minister in the First Pentecostal Church, she founded the Helping Hand Restaurant. There, she offered home-cooked meals for 35 cents each. Those who could not afford to pay for their meals could eat for free and those who could would often pay more (sometimes as much as $3 for a cup of coffee) to cover the cost of meals for others.

“If we serve soul food, you better watch out,” Waddles said in a 1969 interview for Life magazine. “The whole town comes running.”

Waddles’s restaurant was a hit. On any given day, the restaurant was serving more than 300 people. In an article for The Amsterdam News, journalist Herb Boyd wrote, “It wasn’t long before the restaurant’s food and her reputation spread beyond the city, and visitors paraded to her establishment as they do to Sylvia’s in Harlem.”

Eventually, what was once described as a “one-woman war on poverty” became a joint, community-led effort. At one point, more than 200 volunteers provided aid and assistance to the restaurant, in addition to a full-time wait staff. Donations poured in, ranging from beef from Michigan governor William Milliken to funds from the Ford Motor Company.

As the restaurant’s success grew, so did the scope of Waddles’s work. She would go on to establish the Mother Waddles Perpetual Mission, offering services to the community, including a health clinic, tutoring and legal services, and job training and placements. “That’s the keyword: Mission,’’ says Boyd, who was also a founding member of the Detroit Metro Times. “She had a drive and concern to make her community whole, to make them secure, and to make them well nourished too.”

Waddles’s own experiences of poverty guided her work. Reflecting on her childhood, she explained, “I look back at it now as my preparation for the work I do today. I can certainly understand the pregnant girl. I can understand the widowed woman. I can understand the separated woman. I can understand the happily married woman. I can understand them all, and I’ve been that, I’ve been every one of those groups.” Amidst these experiences was a perpetual love for and understanding of community—and, perhaps, a larger, more intimate call to poor women and their relationship to food.

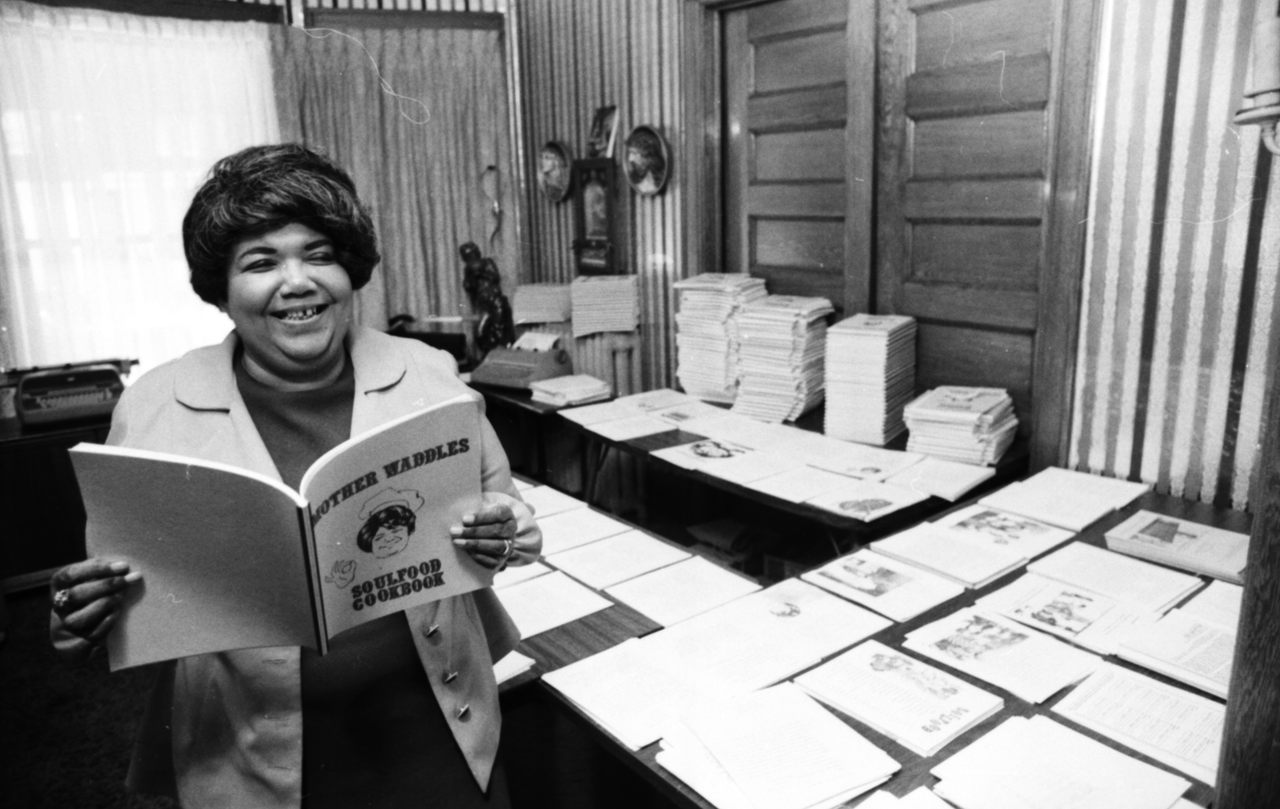

To fundraise for her community services, Waddles self-published two cookbooks, which have sold more than 85,000 copies. In 1970’s The Mother Waddles Soul Food Cookbook, recipes on cornerstone dishes such as baked sweet potatoes, chicken pot pie, and barbecued neck bones are interwoven with self-authored poems. The poetry explored Waddles’s thoughts on far-ranging topics including faith, food, poverty, and even the Vietnam War. In one poem, she reflects on the power of her work in the kitchen:

Remember … creating a meal is a poor woman’s thing,

All she needs is imagination and a gospel song to sing.

Waddles’s cookbook referenced larger traditions of resiliency. She included beloved meals that were served to family, friends, and of course, the community. Her recipes were resourceful, ensuring that every part of an ingredient was used to the fullest extent. The excess broth from her Cabbage Greens and Dry Beans recipe becomes the base of the “Pot Licker” recipe later in the book. Historian Vaughn A. Booker would later write in Faithfully Magazine, “The significance of her labor in producing this cookbook was to impart an understanding of food—specifically, ‘soul food’—that gives meaning to the people who produce it: relentlessly resourceful African-American women with sole responsibility for their children’s well-being in this world, no matter the circumstances that left them as such.”

Between her community services, restaurant, cookbooks, and contributions during the unrest of the summer of 1967, Waddles’s work did not go unnoticed. She won the 1968 Sojourner Truth Award from the Detroit Club of the National Association of Negro Women’s Club and was later inducted to the Michigan Hall of Fame. When recording an oral history in 1980, Waddles recalled an event in which she spoke before college students in Livonia, Michigan. “They said to me, ‘Mother Waddles, if you were not a missionary minister, what do you think you’d be?’ I said, ‘A revolutionary.’” According to Waddles, civil rights activist Roy Wilkins, who was also in attendance that day, responded, ‘‘Mother Waddles, you’re already that.”

When she passed away in 2001 at 88 years old, the city grieved. Detroit mayor Dennis Archer said, “Mother Waddles’s loss is Detroit’s loss.” But even though the Mother Waddles Perpetual Mission and Helping Hands Restaurant were forced to shut down after multiple fires and financial setbacks, Waddles’s legacy lives on in the work of culinary activists that follow in her footsteps.

One such activist is chef Phil Jones, the winner of the Detroit Free Press 2021 Chef of the Year, who also works to improve local food systems. A former restaurant chef with an extensive culinary background working at notable Detroit establishments, Jones shifted his focus to feeding some of the city’s most vulnerable citizens. For Black culinary creatives, he explains, food is a portal to a larger history and a larger commitment to the individual and the community. “I wouldn’t say it’s giving back. It’s an exercise in self-preservation,” he says. “I’m happy when my community is happy.”

Feeding more than 5,000 Detroiters for free through the Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen initiative, Jones’s work continues Waddles’s legacy. “Mother Waddles and her work in the community is an inspiration for a lot of folks and for myself in particular. It has been a guiding force for trying to help people where they are.”

To learn more about Charleszetta Waddles in her own words, you can listen to interviews conducted by the Harvard Library Black Women Oral History Project.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook