The Legend of a Cave and the Traces of the Underground Railroad in Ohio

In 1892, a newspaper described a cave that sheltered 21 formerly enslaved people. Ohioans are still looking for it.

When Donald Altstaetter was growing up, not far from Middletown, Ohio, he overheard a mysterious conversation between a local landowner and a hunter. The landowner was willing to allow the hunter onto his property, but only if he stayed away from a specific area. “If I find out you’ve been there, I’ll never allow you back,” Altstaetter remembers the landowner saying.

Alstaetter is now a retired high school principal in his 90s, yet all these decades later, he has never forgotten that conversation. The landowner’s words remind him of a dark local legend, rooted in several newspaper articles from 1892. Before the Civil War, homes in this part of rural Ohio were a part of the Underground Railroad. Once, the story goes, a nearby cave provided shelter to 21 people who were escaping slavery in the South. But the cave is said to have filled with toxic fumes, and purportedly became a sealed tomb.

More than 150 years after the end of the Civil War, the story of the cave still has a remarkable hold on the local imagination. Marlese Durr, a sociology professor at Wright State University who has studied the legacy of slavery, calls it “one of the first mysteries of the Underground Railroad in Ohio.” Durr hopes that it will inspire people to look more closely at history, and help them see that slavery is not a closed chapter. “They think it is over, but it isn’t over,” she says.

On a late-winter day in early 2019, before invasive honeysuckle has had a chance to strangle the forest floor, Altstaetter walks slowly toward the edge of a patch of woods. His steps are labored, his walker sinks into the mud with each step. “Up there,” he says, referring to the cave. “It’s up there.” Years earlier, he had seen a spot where the rocks looked disturbed and inconsistent with the surroundings.

Above him, runoff from a spring cascades down a hillside, covering jumbles of boulders in a watery sheen. Madison Township, on the west side of the lumbering Great Miami River near Middletown, is honeycombed with numerous such creeks, ravines, abandoned mines—and, just maybe, caves.

Chris Carberry, a longtime local who has searched for the cave, has joined today’s search. We leave Altstaetter on the path below, wondering whether we could solve a mystery that has haunted this township for generations. Following Alstaetter’s instructions, we climb and inspect a gorge, examining the occasional boulder, scrutinizing each outcropping of rock.

But after two hours of searching, we come up empty. Halfway up the slope, there were some neatly laid rocks, as if someone had once tried to build a wall here. But there is no sign of a cave.

In the summer of 1892, a writer identified only as “John” wrote a dramatic account about a cave filled with poisonous gases and filled with skeletons, and claimed that it had been sealed so that no one would ever stumble into it again. The account said the cave was six miles from Middletown, Ohio, and quoted John’s father: “I saw the bones of many men, how many I could not count. John, I will never, never enter that cave again…”

John’s narrative might well have been forgotten, but in the 1980s, a local historian from the Middletown area rediscovered it and wrote a new article for the local paper. The dispatch launched a generation of would-be spelunkers, including myself. The search is not entirely about adventure-seeking—it is also about paying homage to what would be a horrific incident along the Underground Railroad. Some have suggested that a memorial would be in order, if the story is true.

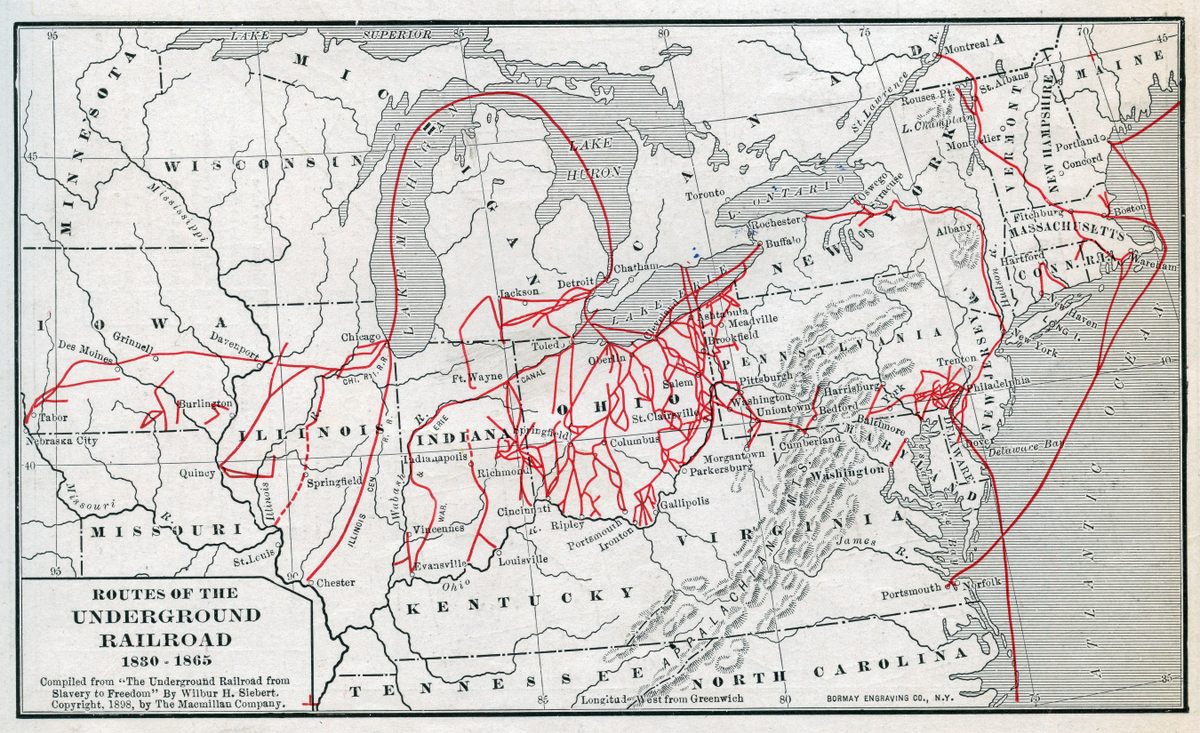

Ohio was one of the busiest places on the Underground Railroad, the somewhat misleading name given to a network of abolitionists and safe houses that helped enslaved people escape to the North. In the countryside west of Middletown, a network of abolitionist Quakers provided shelter as escapees made their way to Canada.

According to John’s account, one summer night in 1849, a group of escapees took shelter in the home of a Hamilton, Ohio, abolitionist and physician, about 10 miles south of Middletown. As the night wore on, the physician grew nervous that bounty hunters were approaching. He loaded his guests into two wagons and headed north, following an empty road that wound along Elk Creek. John claimed that the doctor ushered the group into a little-known cave, where they’d be cramped and cold but safe and unseen. The cave was on the property of an abolitionist sympathizer—John’s father.

In the newspaper story, the doctor runs to the farmhouse and knocks. It is well after midnight. “I told him what I knew of the cave, that it was a deathtrap and that I was sure not one of the twenty-one would emerge alive,” John’s father says. He tells the doctor that geologists from the “Department of Washington City, DC” had also visited the cave, several years before, and had never returned.

As unlikely as the story of the cave may sound, many locals have tried to confirm its existence. “I think it’s 50-50,” says Larry Helton, a local historian who has searched for it. Jeff Richardson, a geology professor at Columbus State Community College, says it might not have been a cave at all, but something known as a “joint” in the rock, which is more like a crack or a fissure. Altstaetter, who compiled a dossier on the cave, agrees, and theorizes that natural gas could have caused suffocation inside. (Natural gas is not known to be found in the area, but Chris Carberry, whose ancestors were in the West Elkton Quaker underground, says a well driller found evidence of natural gas on his property.)

Many experts on local geology are skeptical. “I personally doubt the account,” says Bill Addington, an avid caver and member of the Cincinnati Grotto Club. “My experience is that in southwest Ohio, the limestone bedding planes are too thin to support the development of caves that would be large enough for people to enter.” Another leading cave expert went so far as to call the story “rubbish.”

One location that comes up frequently among those searching for the cave, including Alstaetter, is the Elk Creek MetroPark in Butler County, but Kelly Barkley, the communications director for the park system, says that’s just a rumor. “No past or current mapping suggests or supports the existence of any cave,” she says.

Still, Erin Hazleton, a cave specialist with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, says subterranean caverns in Butler County aren’t out of the question. Hazleton says that the area “does have karst features such as sinkholes and caves,” which form when carbonate bedrock is dissolved by water. Cavers have scoured history books for leads, she says, “but it is certainly possible we missed a cave, and we find new caves every year as testament to that.”

In 1997, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, prompted by Alstaetter, commissioned a study to try and find the cave. After an exhausting field search and numerous interviews, the report came to no conclusion. The study was led by Mary Ann Olding, who has researched the history of black rural communities in Ohio. She spent days with archaeologists exploring a tract of land in Madison Township, but came up empty. “Still, I think it seems believable,” she says of John’s story.

Tom Calacro, the author of several books about the Underground Railroad, including The Search for The Underground Railroad in South Central Ohio, also finds the story plausible. He believes the absence of records of the tragedy is easily explainable. “Slaves didn’t have last names, they were considered property, they could disappear very easily,” he says. “I think it is very possible they could have died in the cave, and no one would know what happened to them.”

Could the story somehow have been a work of serialized fiction? Durr, the sociology professor, doesn’t think so. “I think the story is very plausible,” she says. “Why make something like that up?” She wonders whether the tale of the cave could perhaps be recovered in some family’s oral history. The Underground Railroad was secret by nature, and so the historical record is often patchy, but the stories of formerly enslaved people can live on among their descendants. “They made up songs and spirituals to tell the stories of their journey,” Durr says.

There is one other scrap of evidence that casts doubt on the story of the cave. “John” wrote that geologists from Washington, D.C., visited the cave in 1845, and never emerged. The U.S. Geological Survey didn’t exist then; Douglas Wilson, staff historian for the Army Corps of Engineers, couldn’t find a record of any geologists employed at the time, or any casualties.

Even after all the unsuccessful efforts to find the cave, the mystery lives on in this part of Ohio, and locals are likely to keep searching for it. Donald Anstaetter retired in the early 1990s and moved to Florida, but he never forgot the cave. In fact, it was one of the reasons that he recently moved back to Ohio, to spend the late years of his life. “I drove a thousand miles back to Ohio just so I could look for the cave,” Altstaetter says. Recent surgeries have slowed him, but he says his quest will continue. “I am thoroughly, totally convinced it exists, and I hope to see it before I die.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook