Michigan’s Bloodsucking Parasite Is Britain’s Royal Delicacy

Lamprey pie is a coronation tradition.

In 2002, Martin Kirby, a journalist and resident of Gloucester, England, had a problem. Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee was coming up fast, and he wanted to provide a traditional lamprey pie for the occasion. After all, for the Queen’s coronation in 1953, the city had supplied the new monarch with a truly epic pie: a 42-pound, 18-inch-high pastry masterpiece decorated with the Royal Coat of Arms and crown.

Kirby is a founding member of the Court Leet of Barton St. Mary, a group of Gloucester history enthusiasts who have brought back centuries-old traditions like declaring a “mock mayor.” “We had the idea of resurrecting the lamprey pie for the monarch, in honor of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee,” Kirby says. Gloucester’s medieval custom of whipping up seafood-filled pies for the royals was revived for 1953, and Court Leet of Barton St. Mary wanted to bring it back once more.

The only catch: sea lampreys, which once slithered plentifully through the River Severn, were on the brink of extinction in the United Kingdom. “We can’t use lamprey from this country, because they’re a protected species,” explains Kirby. “The city council of Gloucester didn’t know where to get the lamprey from. But I did.”

The sea lamprey, or Petromyzon marinus, looks like something dredged up from the depths of hell. Virtually unchanged over the last 360 million years of evolution, each of these three foot-long “living fossils” resemble eels or fish, but happen to be neither. These parasites have a gaping suction cup ringed with row upon row of teeth for a maw. After attaching themselves to the sides of other cold-blooded swimmers, they use their serrated tongue to rasp away scales and leech away blood, slowly killing their prey.

Despite their uncanny resemblance to the Sarlacc from Star Wars, lampreys have been a delicacy in England for centuries. In the 12th century, King Henry I was so fond of them that, according to the chronicler Henry of Huntingdon, he died in 1135 in Normandy of a “surfeit of lampreys.” This unfortunate incident may have been why the citizens of the city of Gloucester opted not to send King John a lamprey pie in 1200. Yet the monarch was so angered that Gloucester “did not pay him sufficient respect in lampreys” that he fined them in revenge.

From then on, Gloucester supplied lamprey pies to the royal court for special occasions. By 1229, King Henry III was so insistent on getting his cut that he declared, “none shall buy or sell lampreys until John [the King’s cook] shall have taken as much as needed for the King’s use.” In 1917, with England embroiled in war, the monarchy decided to scrap the tradition, only to revive it for the queen’s coronation. In subsequent years, lamprey supplies dwindled and the pies fell out of favor again.

Yet as dams and industrial pollution destroyed the lamprey’s spawning grounds in the UK, these resourceful vampires made their way from the Atlantic Ocean into the lakes and rivers of North America via man-made waterways. In Britain, they are protected, but across the pond, they’re a dangerous invasive species.

“They are the killer-bee-bad-cousin-at-the-buffet that no one wanted,” says Marc Gaden, communications director and legislative liaison for the Great Lakes Fishery Commission. “They’re really, really destructive.”

Sea lampreys are native to the northern Atlantic, but until humans transplanted them, they had no place deep in the interior of North America. Starting in the late 1800s, lampreys wormed their way through the Erie Canal into the Finger Lakes. By 1835, they had made their way to Lake Ontario, where they stayed for decades thanks to the natural barrier of Niagara Falls. In 1938, they began showing up in Lake Superior and around the Great Lakes in droves.

“It’s a bit of a perfect storm,” Gaden says. “They’re not very picky eaters. There are a lot of fish that they like—trout, walleyes, sturgeon. It’s an open buffet with nothing keeping them in check.”

Larger and more ravenous than their North American cousins, invasive lampreys quickly began decimating the local fish populations. A single female lamprey lays between 30,000 and 100,000 eggs at a time. Since soft silt at the bottom of the Great Lakes tributary streams is ideal spawning ground for lamprey larvae, their numbers can grow quickly.

By the 1960s, sea lampreys were killing 100 million pounds of fish in the Great Lakes each year. Eighty-five percent of the remaining catch still bore gashes and circular teeth marks.“They leave gruesome, bloody wounds that cause the fish to die by infection,” Gaden says.

Thanks to decades of culling, conservationists have managed to somewhat keep sea lampreys in check. “We often joke that if [sea lampreys] looked like bunnies or puppies, we might not have society’s blessing to keep them under control, but in this case no one objects,” says Gaden. Nevertheless, the Great lakes Fishery Commission still has a serious surfeit of lamprey. When Gaden first got the call from Gloucester in 2002, he was all too happy to ship them over.

“Marc Gaden is knee-deep in lamprey, so he FedExed them over to us,” says Kirby. He advised the city of Gloucester to do the same for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. Gaden’s lamprey wound up in a masterpiece of architectural pastry shaped like Gloucester Cathedral.

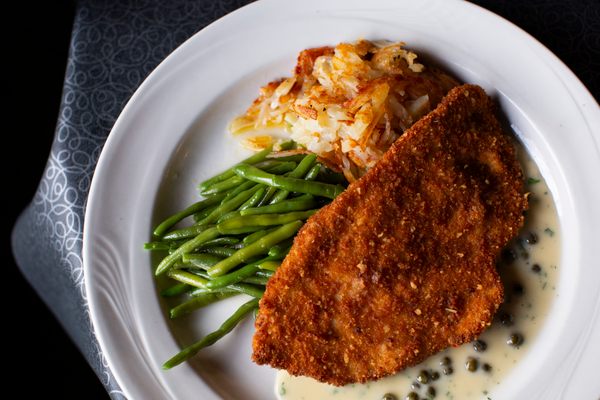

According to Kirby, the good people of Gloucester drew inspiration for their pie from medieval recipes. For security reasons, the queen didn’t actually partake of the pie, so the taste wasn’t overly important. “It’s a symbolic thing now; it’s not actually going to be eaten,” Kirby says. “When we made the 2012 one, our local area TV crew cooked some of the lamprey and mixed it with bacon and some potato mash. They said it was all right.”

Since that first pie 20 years ago, Gaden has journeyed to visit Gloucester in person and befriended Kirby. “I am the purveyor of the lamprey to the Court Leet of the City of Gloucester and I have a certificate to prove it,” he says with a laugh.

As to whether or not his services and lampreys will be requested for the upcoming coronation banquet, he can’t say yet. “Whether they do one for King Charles III, I don’t know, but I stand ready,” Gaden says. “All I can tell you is I’ve been very happy to be a part of this tradition.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook