How Survivors of Stalinism Created a New Korean-Fusion Cuisine

When the Koryo Saram were forcibly relocated, they forged new identities.

In 2010 Dave Cook, a food writer with a talent for highlighting lesser known cuisine, endorsed a mom-and-pop cafe just off Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach boardwalk in the New York Times. By writing about the restaurant, which is known interchangeably as Eddie Fancy Food, Cafe At-Your-Mother-in-Law, or Y Tëщи, he gave most Americans their first look at a unique fusion cuisine: Korean-Russian-Central Asian, or Koryo Saram, food.

Ever since, interest in this subtle blend, which mixes the heavy yet cool flavors of the Eurasian steppe with the fire and tang of the Korean peninsula, has exploded. Enticingly, though, it does not simply mix-and-match the traditions’ ingredients. Koryo Saram food presents, for example, a standard Central Asian dish, such as lagman, a cool beef noodle soup, straight up, only revealing an unexpected dash of fermented Korean chilis when diners taste it on the tongue. And chim cha salads often look for all the world like white kimchi, but one bite reveals cabbage deep soaked in vinegar, rather than fermented, and sometimes cut with distinctly Central Asian flavors, such as pickled tomatoes. Tourists from across the U.S. and as far as South Korea now visit Y Tëщи, or Brooklyn’s other Koryo Saram eatery, Café Lily.

Yet Koryo Saram food is not like other Korean fusions that have caught the public eye. Mixes like Korean-Mexican food are often the result of serendipitous encounters between American immigrant communities and intentional experimentation by chefs. Koryo Saram food, though, is in many ways the creation of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, a product of a massive and brutal ethnic cleansing campaign.

Koreans have likely lived in the slice of Russia above North Korea and east of China for centuries, says Jon Chang, an ethnographer of the population, albeit in small and perhaps itinerant numbers. The population exploded not long after Russia acquired the region in a treaty signed with China in 1860. Drought and famine in Korea’s northeastern Hamgyong province sent thousands across the border, until they outnumbered imperial settlers in some areas. Russian Czars initially welcomed the Koreans as part of efforts to tame their new territory, a surprisingly warm and hospitable, but still mountainous, forested, and rugged and remote corner of the Russian Far East. As regional historian Dae-Sook Suh has documented, though, Russian rulers grew increasingly racist and nervous, attempting to shut the border with Hamgyong and offering citizenship and land only to Korean settlers who agreed to embrace Russian culture and the Orthodox Christian faith.

Many Koreans played ball with Russia. They joined the imperial army and fought in the Russo-Japanese War and World War I, and they joined the Bolsheviks in holding the territory against foreign incursions from 1918 to 1922. By 1923, up to 100,000 Koreans lived in the region, and those who lived in or near cities, says Koryo Saram academic and Kazakhstani native Dr. German Kim, had adopted Russian culture and language. Soviet cultural and nutritional policies in the 1920s, notes Jeanyoung Lee, a Koryo Saram foodways scholar, also introduced them to European staples, such as breakfasts of bread, milk, and coffee. “In kindergarten in the Soviet times,” says German Kim, “all the kids ate standard foods. It was all regulation, to make all people the same.” Many, German Kim adds, saw themselves as distinct from their peninsular kin.

Still, Hamgyong culture and food maintained strong footholds in the region: Koreans in urban centers lived primarily in ethnic enclaves, while farmers rarely encountered Russian culture. Immigration from Hamgyong continued too, especially after Japan seized the Korean peninsula in 1905. By the mid-1930s, says German Kim, only half of all Koreans in the area were meaningfully assimilated, and most still spoke the Hamgyong dialect. They grew Hamgyong ingredients, such as rice, millet, potato, cabbage, and pepper, and cooked and ate Hamgyong foods, such as seaweed soup with crab, millet porridges, pollock fish dishes.

“The Koreans were a strong social group who maintained their language and culture during the first generations in the Russian Far East,” says Michael Vince Kim, an Argentine-Korean photographer who has documented Koryo Saram communities. “They had founded cultural establishments, such as newspapers, radio programs, cultural centers, as well as theaters.”

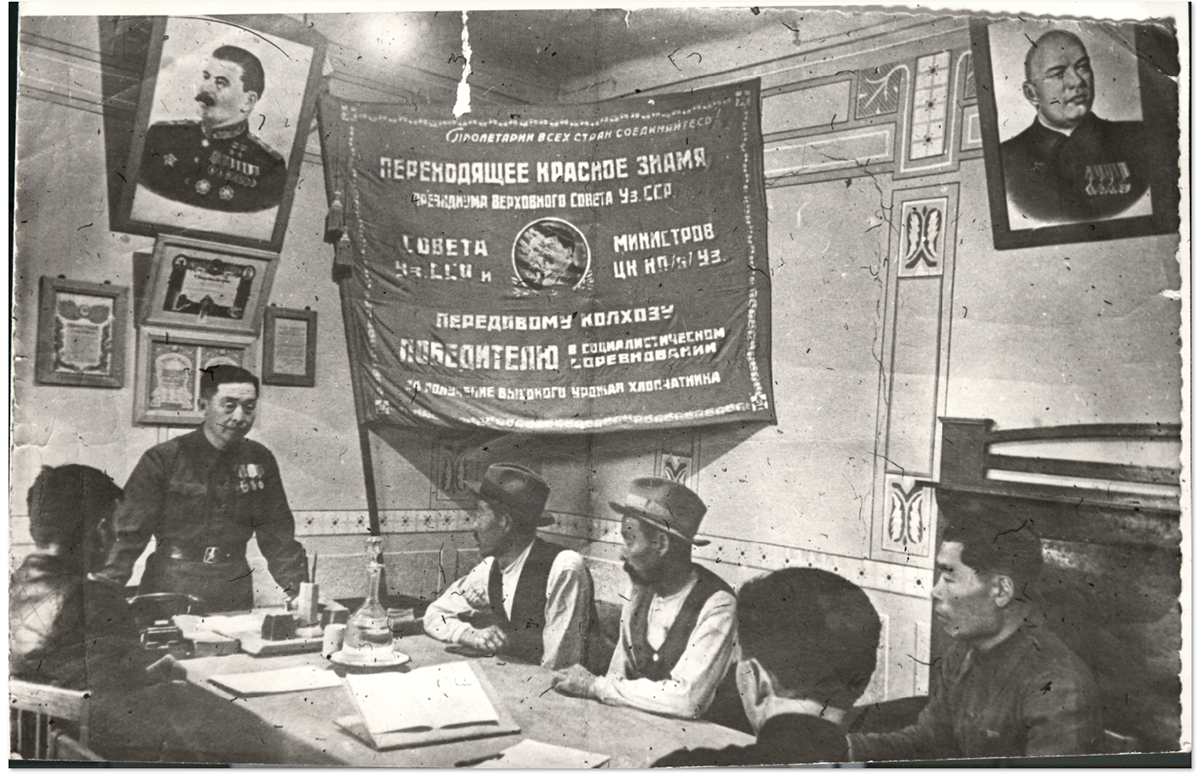

Then in 1936, with no warning, evidence, or clear precipitating event, Soviet agents rounded up hundreds of Koreans, accused them of being Japanese spies, and killed or imprisoned them. In 1937, officials suddenly gave the more than 170,000 Koreans in the Far East days to pack their belongings. They forcibly relocated some 95,000 to Kazakhstan and 76,000 to Uzbekistan, in what was then the USSR.

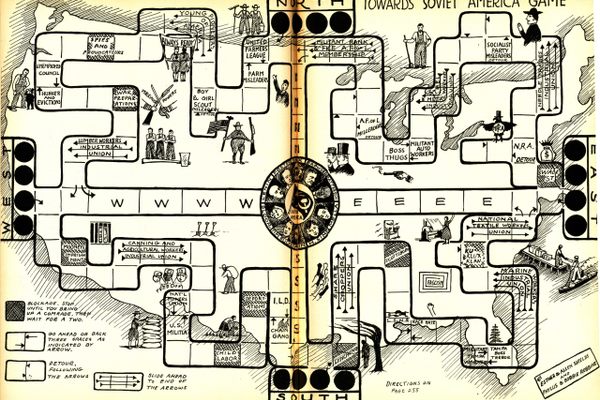

This was not the first time the Soviet Union engaged in ethnic cleansing. In 1935, officials moved at least 7,000 Finns out of the Leningrad region, and in 1936, they relocated 20,000 Finns and almost 36,000 Poles and Ukrainians. But the Korean cleansing was the largest prelude to a wave of forced deportations throughout the 1940s, which swept millions of minorities, especially from the Caucasus, Ukraine, and the European border, from their homes to often remote parts of Central Asia and Siberia.

Historians still debate the logic and logistics of these cleansings, which were justified officially by notions that entire ethnic groups were disloyal, but perpetrated unevenly. In the Korean case, scholars such as Chang have convincingly argued that the purge was an extension of longstanding anti-Asian racism—an insistence on seeing a loyal frontier group as a scheming, forever-foreign other.

All of the purges, though, were sudden and brutal, corralling tens-to-hundreds of thousands into cattle cars, killing those who resisted or could not travel, tossing the dead aside in transit, and dumping survivors in ill-supplied labor camps, where between a third and half died of illness, starvation, and exposure within the first year. Nikolay Ten, the son of Korean exiles, told Uzbek-Korean writer Victoria Kim that, on the trains, families like his collected snow for meltwater and traded belongings in towns they passed for survival rations. At least 72,000 Koreans died on the month-long, 4,000-mile journey, or during the early months of camp life.

Survivors found their lives upended. In an interview with Chang, Elizaveta Li, a native of Vladivostok in the Far East, recounted losing her father to the Soviet roundups, being shipped to Uzbekistan, and losing her best friends and neighbors, Suna and Kuna Tsoi, who were relocated some 500 miles away in Kazakhstan. They never saw each other again.

The communities the exiles formed in Central Asia could have fostered an even stronger, insular Korean identity. Given their strong agricultural roots, the Soviets wanted them to cultivate Central Asian swamps, and they set up remote, often all-Korean work camps and farming towns. Suh’s research on these communes showed, by the 1980s, that only one in 20 married a non-Korean.

But especially in the early years, conditions in these communities were harsh and the environment was foreign. An Uzbek-Korean survivor told Chang that they ate whatever they could, including birds, dogs, and rabbits. Nikolay Ten recounted food shortages into the 1950s, which forced his mother to bake grass bread to survive.

After some initial caution, Chang notes, locals developed ties with the Koreans, helping them learn what to hunt, grow, and eat. Aside from the rice and other staple crops they grew on their farms, this new local diet lacked many Hamgyong standards, such as seafood and, due to the region’s Islamic bent, pork. The Soviet Union also made efforts to eliminate Korean cultural institutions and impose Russian language, ways of life, and, of course, foodways.

While all the USSR’s forcibly deported peoples faced similar cultural pressures, Soviet Korean culture and food witnessed perhaps the most dramatic transformations, says Pohl. They had undergone less Russianization, and their food and culture was especially distinct from their area of exile. And while most exiled populations were resettled to their home territories in 1957, four years after Stalin’s death, the Koreans, like a few other groups, didn’t get to go back to the Far East. Moreover, says German Kim, the Koreans, having lived in that region for a few decades at most, didn’t feel like they had a home to return to. “Other peoples were all dreaming of going back to native places, preserving their identity, language, cuisine, customs,” he says of groups who remained in exile post-Stalin. “The Koryo Saram had no dream.”

So, more than any other group, they decided to integrate into Central Asian-Soviet society. They shed their dialect, to the point that few today even speak it as a heritage tongue, intermarried at higher rates, and as German Kim put it, “began to eat Russian bread and drink Russian vodka.”

By the 1960s, says Kim, the deportees had developed a distinctive culture and started, at a critical mass, referring to themselves as Koryo Saram. Soviet nutritional policies, familial blending, and a radically different environment produced major culinary shifts that worked heritage flavors into primarily Central Asian or Russian dishes, and used steppe flavors and cooking techniques in the Korean soups, salads, and other sides that could still be readily made in the region.

Not every family experienced the same level of blend; Michael Vince Kim notes that he’s met at least one Koryo Saram woman in her 90s who still primarily cooks recognizably Korean food. But for many, combined with the fact that the rural Hamgyong cuisine was already distinct, these influences have led to a complete break with Korea.

“The first time I came to South Korea,” says German Kim, “I couldn’t recognize a lot of their cuisine. There are many things in South Korea I still cannot eat. I don’t like how it smells.”

The Koryo Saram story is hardly unique in human history. Many American culinary traditions, for example, are defined by the forced movements and cultural deconstruction of African slaves or Native American tribes. The freshness of the Koryo Saram’s trauma, though, and the centrality of it to any review of a cafe like Brooklyn’s Y Tëщи, serves as a reminder of the importance of looking for and recognizing the pain that forged other, older food traditions, in order to better appreciate them and honor the achievements of their often anonymous pioneers.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook