Make Italy’s Christmas Snake Cake

In Umbria, the holidays mean a piece of sweet, almondy serpentone.

In May of 2023, Natasha Contardi of Montreal, Canada, found a decades-old scrap of paper among her grandmother’s belongings with a handwritten Italian recipe on it. Her grandmother, suffering from dementia, no longer recognized the recipe, so Contardi posted photos on Reddit asking for help with the translation. Not only did the online community translate the recipe, they revealed the food mystery behind it. Originally written down by a great-aunt of Contardi’s, the recipe was for serpentone, a traditional Christmas dessert specific to the northern Italian region of Umbria, especially the city of Perugia. Serpentone means “big snake,” and that’s exactly what the dish looks like.

Serpentone typically includes almonds and fruit, but the recipe can vary widely. Some versions resemble marzipan, being molded from equal parts almond flour and sugar that get combined with whipped egg whites for binding. Others are more cake-like and include mashed chickpeas and/or wheat flour. Unusually, Contardi’s great-aunt’s serpentone is flavored with cocoa powder; anise liqueur or citrus zest is more typical. The serpentone may be stuffed with a filling of nuts, dried or candied fruit, or both, or the nuts and fruit may be used only on top to decorate the creature. It’s up to the baker how large, how tightly-coiled, and how elaborately-decorated the snake is. Some sport dragon-like rows of almond spines and flashy candied-fruit scales; others are plain except for beady coffee-bean eyes and a cherry tongue. But the serpentone is always shaped into a snake (or an eel, depending whom you ask), and always curled into a spiral, giving rise to its other name of torciglione, which may be translated as “big twist.”

View this post on Instagram

Numerous stories attempt to explain the serpentone’s origins and its connection to Christmas. Some say the sweet commemorates Saint Anatolia, said to have miraculously emerged unscathed from a room full of venomous serpents in the third century. Others see the serpentone as a Satanic Biblical serpent. In this interpretation, eating the snake at Christmas celebrates another year of triumph over the forces of darkness. But these explanations rely on the Christian view of the snake as a symbol of evil and sin. Another theory instead places the serpentone alongside the Christmas tree, as an example of an ancient, pre-Christian pagan tradition of the winter solstice being folded into later Christian practice.

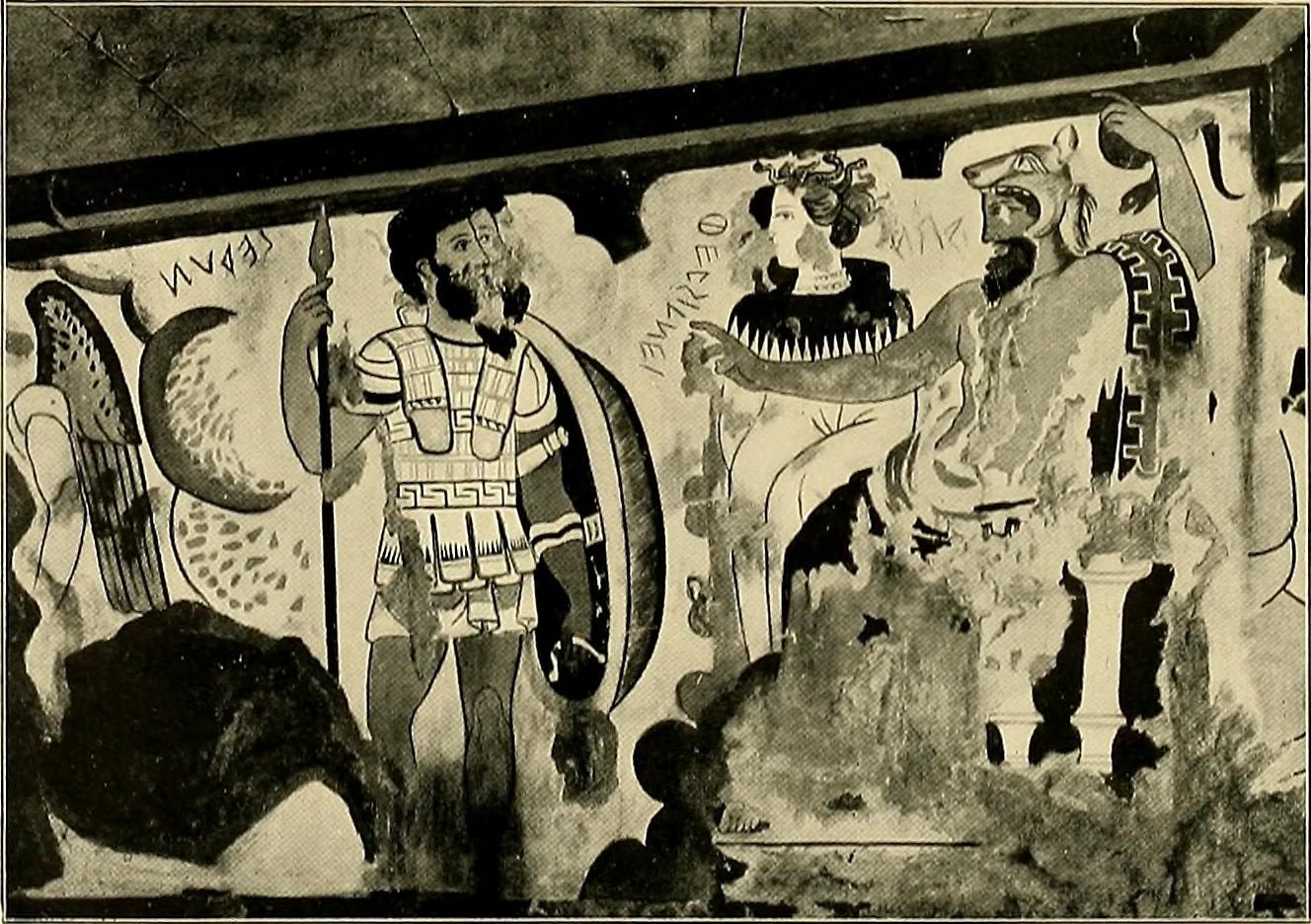

If you search for information about the serpentone online, you’ll find many articles that claim it has some connection to the Etruscans, the ancient people whose civilization flourished in Umbria from the 7th to 2nd centuries BC. While there’s no direct evidence of an Etruscan origin for the serpentone, there are plenty of examples demonstrating the sacred roles that snakes played in Etruscan and other ancient Mediterranean societies. Lisa Pieraccini, an Etruscan art specialist at UC Berkeley, describes snakes as “chthonic figures”—meaning they were associated with the earth and the Underworld—across ancient Mediterranean cultures. In Etruscan funerary art such as tomb paintings, says Pieraccini, “guides down in the Underworld routinely will hold snakes.” She points out that the artists of these paintings must have observed actual animals closely, reproducing the markings of species that still exist today.

In the ancient Mediterranean, the snake’s ability to renew itself by shedding its skin, the fatal venom wielded by some, and the fact that snakes live in dark places close to the ground, connected them with the subterranean world of the dead. The snake’s ability to form a spiral or circle lent further credence to the association, as these shapes in many cultures symbolize the eternally-renewing cycle of life and death.

While it’s not clear whether ancient Mediterranean peoples made cakes in the shape of snakes, there is evidence that they made cakes for snakes. Ancient Greek and Roman sources describe honeyed cakes being offered to chthonic deities in general, but especially to sacred temple snakes, including symbolic versions as well as live “house-snakes” tended by temple priests or priestesses. Herodotus claimed that when the Persian army approached Athens in 480 BC, the city’s temple snake refused to eat its honey-cakes, an omen of doom that led the Athenians to evacuate. However, since snakes are exclusively carnivorous, this must have been an exaggeration. Real temple snakes, notes classics scholar Daniel Ogden, “could not have eaten the honey cakes that served as their symbolic food, and were probably maintained rather with [a diet of] eggs.”

The ancient honey-cakes given to snakes often had a sculpted knob on top meant to resemble a navel, which represented the center of the Earth in Greek religion. Circular and ring shapes, which can themselves be associated with the form of a serpent, were also common in breads baked as offerings in ancient Greece and Rome. Even today in the central Italian town of Cocullo, a festival of the snakes that has its roots in the worship of an ancient goddess is still celebrated with a special ring-shaped cake.

Fried or baked sweets have been an essential part of winter solstice celebrations in Italy since before the Christian era, with every region having its own local variations. Like the serpentone, many of these Christmas sweets linked to pre-Christian customs are made in a symbolic shape, such as a ring, a crescent moon, or a ladder. So it’s possible that Umbria’s Christmas serpentone has ties to the ancient symbolism of both the snake and the spiral, served as the cycle of the year turns.

“I think of [the serpentone’s] shape as that of an ouroboros, the ancient circular emblem of infinity and renewal,” writes cookbook author and Perugia native Letizia Mattiaci, “a most fitting symbol for the winter solstice or for Christmas and New Year.”

Mattiaci notes that debate continues among modern Umbrians as to which animal the serpentone is supposed to be, a snake or an eel, with another colorful origin story claiming that “a nun made the pastry in the shape of an eel to honor a visiting coastal priest, since no fish was available in the monastery” (though Mattiaci opines that the serpentone’s protruding tongue proves it’s a snake). This confusion runs deep: The modern Italian word for eel, anguilla, traces from the Latin for “little snake,” and is related to Anguitia or Angitia, the goddess connected to Cocullo’s festival.

If you look around the modern Mediterranean, you’ll find other Christmas sweets that resemble Umbria’s serpentone. In Emilia-Romagna, not far from Umbria, the biscione, which also means “big snake” in the local dialect, is decorated with frilly meringue scales. Other examples farther afield land squarely on the other side of the snake vs. eel debate. In Toledo, Spain, there’s the anguila de mazapánis, meaning “marzipan eel.” Portugal has the lampreia de ovos, an eel-like lamprey fish made with golden egg yolks. A connection might also be drawn to Bulgarian banitsa, a spiral cake served at Christmas and New Year, but here the meaning of the spiral seems more significant than the snake, since banitsa is not meant to look like an animal, and resembles styles of burek pastry seen throughout the former Ottoman Empire. Serpentone has also been adapted as a Jewish holiday food in the northern Italian city of Urbino, where it is served for Passover and said to represent the staff of Moses that was miraculously turned into a snake in the Book of Exodus, though this version is not always curled into the classic spiral shape.

Whether snake, eel, lamprey, or simply a spiral, and whatever the serpentone’s origins, its celebratory shape recalls the promise that the new year holds. Whimsical and full of potent symbolism, Umbria’s festive serpent also happens to be delicious, and quite easy to make yourself.

Serpentone

- Prep time: 20 minutes

- Cook time: 30 minutes

- Total time: 50 minutes

- 8–10 servings

Ingredients

- 1 ¾ cups almond flour

- 1 ¾ cups sugar

- 2 eggs

- Zest of one lemon or one orange

- Candied fruit, nuts, and/or coffee beans for decorating

Instructions

-

Sift the sugar and almond flour separately to remove lumps.

-

Rub the lemon or orange zest into the sugar with your hands until well-combined (this step helps to release more of the flavorful citrus oils).

-

Mix the lemony sugar into the almond flour.

-

Separate the egg yolks and whites. Beat the egg whites into a stiff foam.

-

Fold the egg whites into the sugar and almond flour mixture, about half a cup at a time, and mix until well-combined into a moldable dough.

-

Shape the dough into a snake and curl it into a spiral shape, with the head on the outer edge of the spiral. Lay the snake on top of a piece of parchment paper on a baking sheet.

-

Decorate the snake by sticking pieces of candied fruit, nuts, and/or coffee beans into the dough. The serpentone can be as elaborate or simple as you like, but at minimum, it should have eyes and a protruding tongue. You can also create the appearance of scales by snipping the dough with scissors.

-

Brush the top of the snake with the reserved egg yolks, being careful not to disturb your decorations.

-

Bake at 350 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes.

- Slice and enjoy with coffee.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook