How a Literary Prank Convinced Germany That ‘Hansel and Gretel’ Was Real

A 1963 book purported to prove that the siblings were murderous bakers.

Few fairy tales are as popular and beloved as the Brothers Grimm’s “Hansel and Gretel.” First published in 1812, the tale has been interpreted, revised, and parodied in myriad ways through the years. So one can imagine the furor in 1963 when a German writer claimed to have uncovered the real story behind the fairy tale.

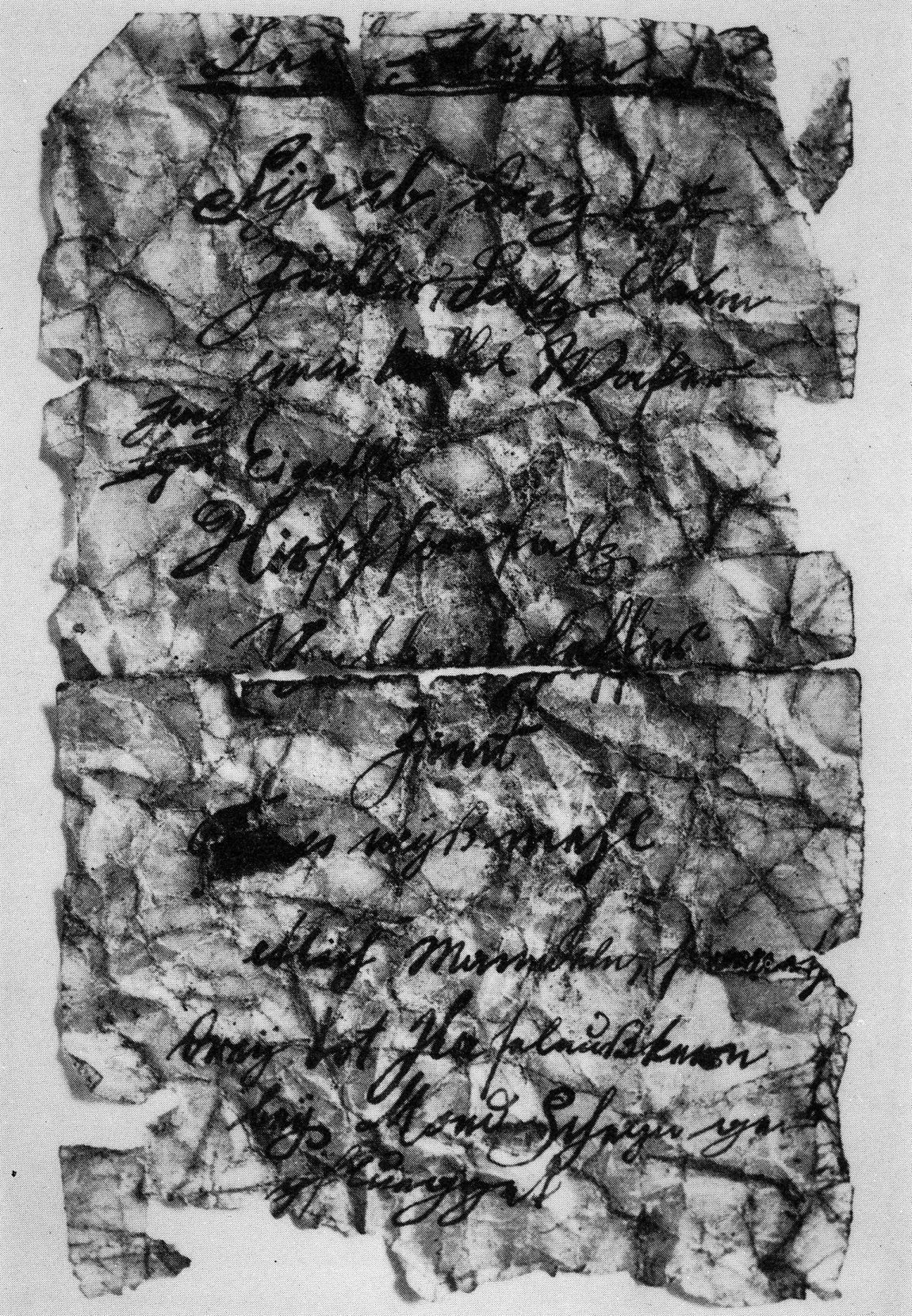

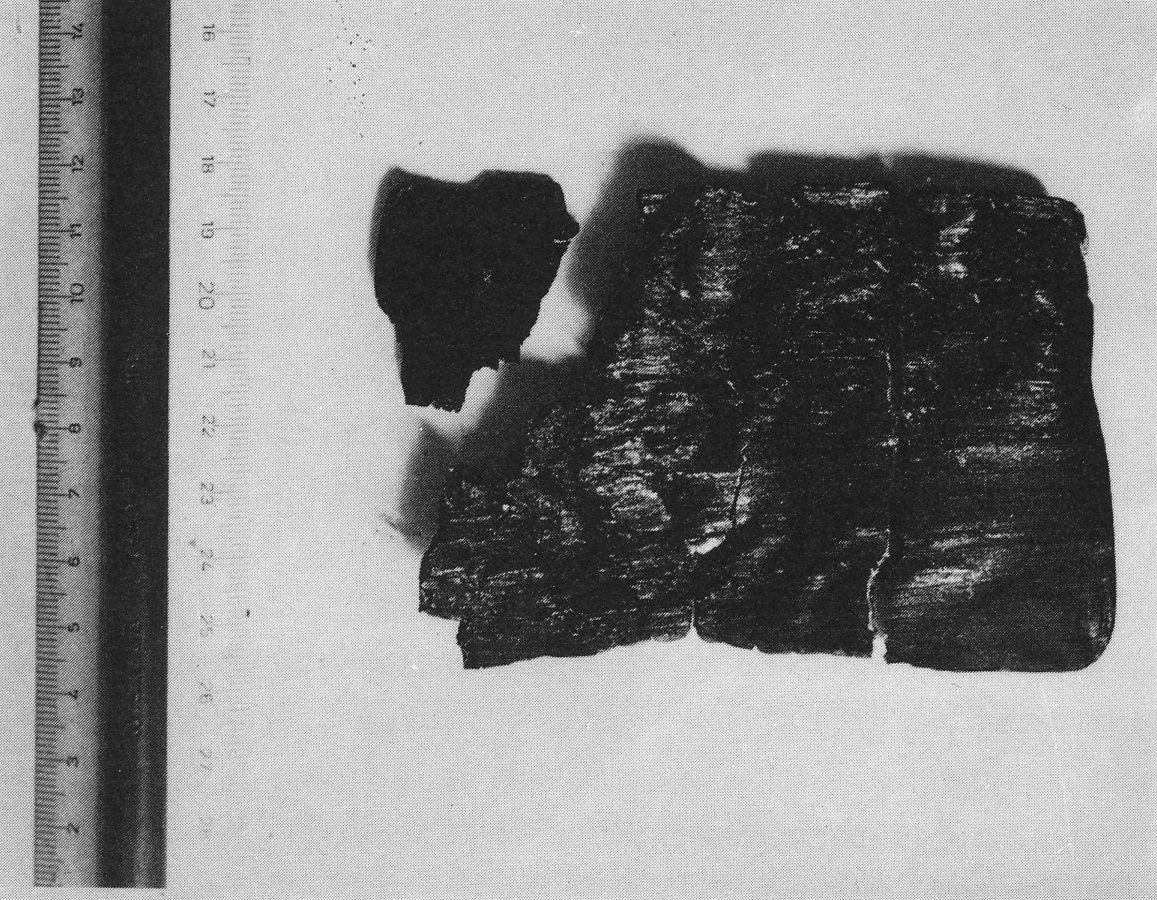

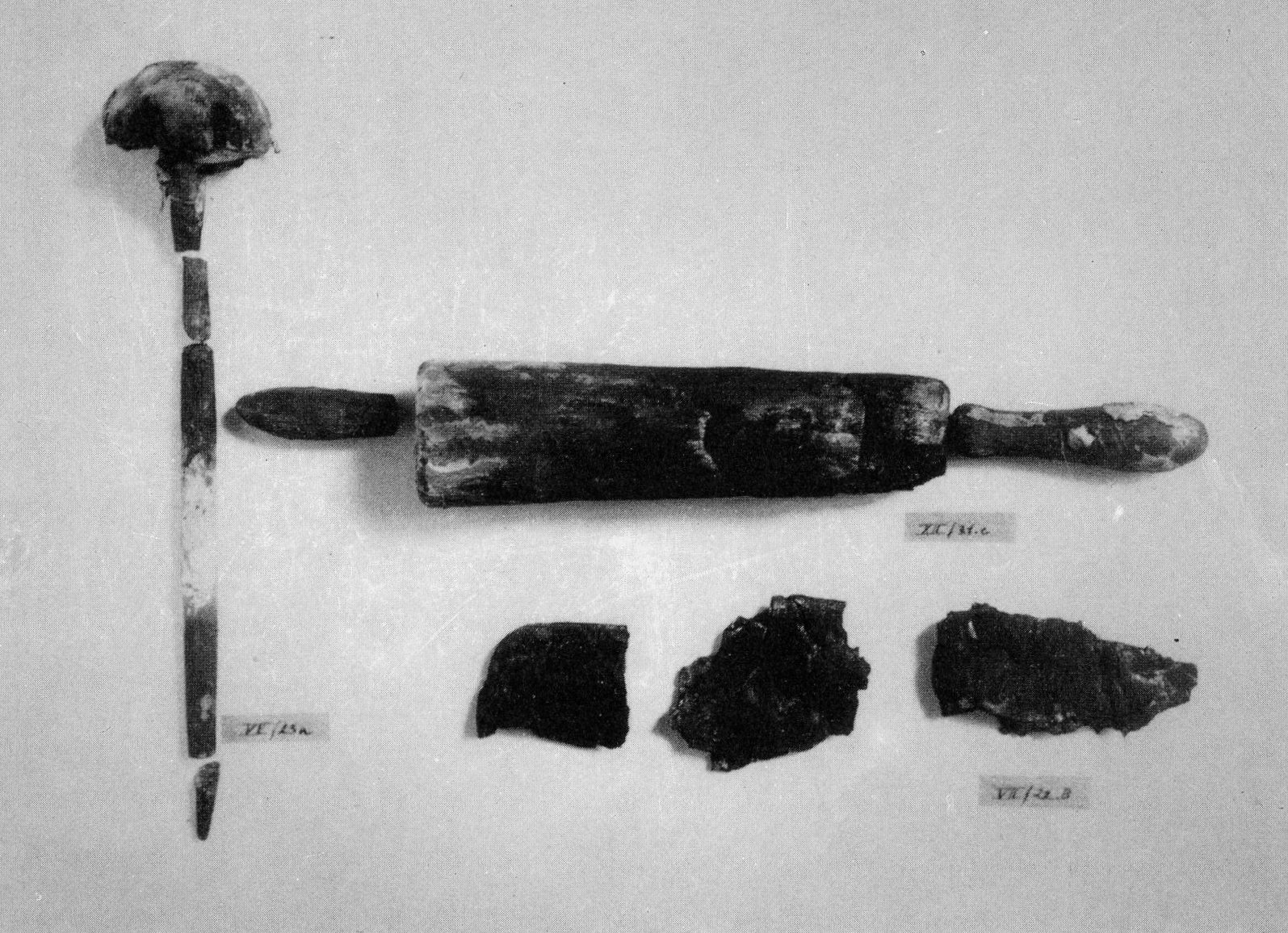

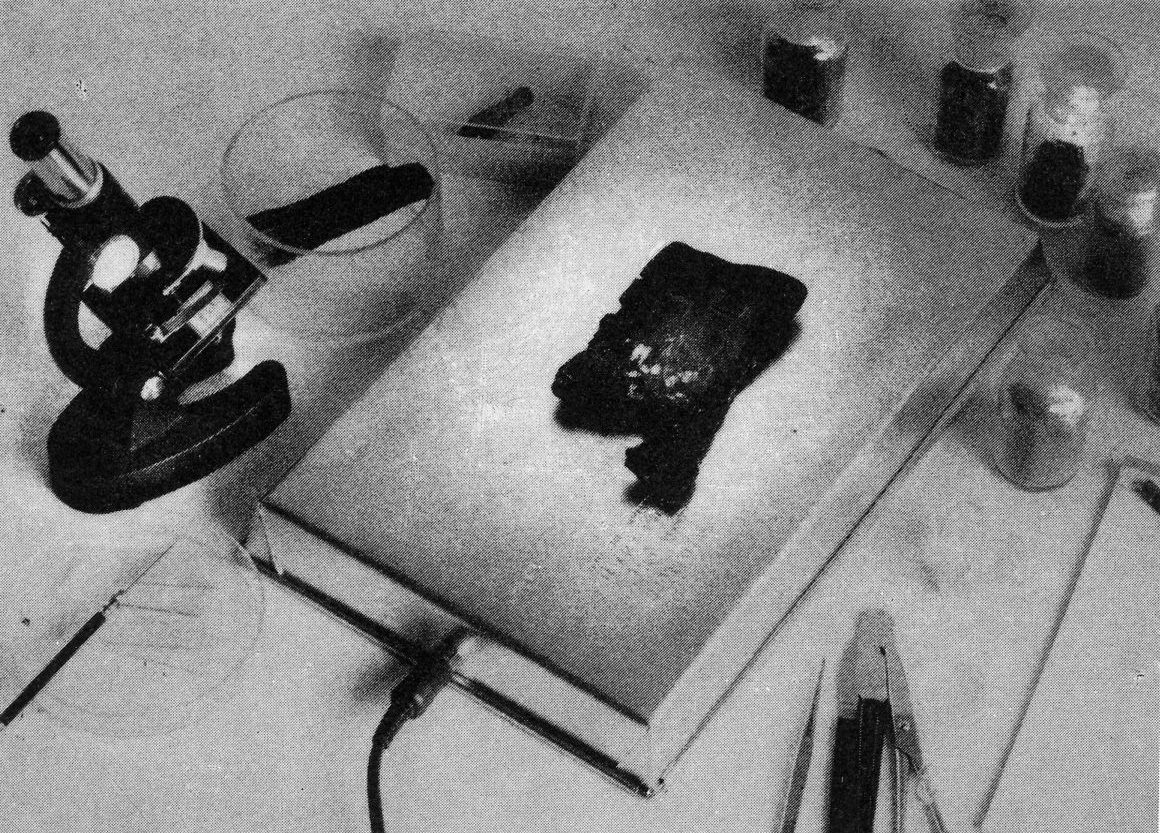

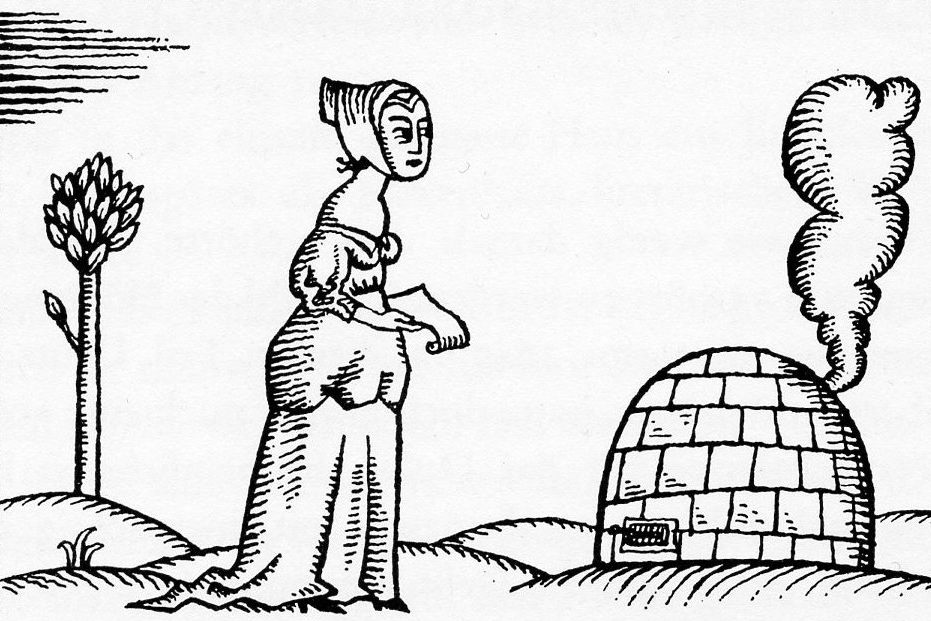

According to Die Wahrheit über Hänsel und Gretel (The Truth About Hansel and Gretel), the two siblings were, in fact, adult brother and sister bakers, living in Germany during the mid-17th century. They murdered the witch, an ingenious confectioner in her own right, to steal her secret recipe for lebkuchen, a gingerbread-like traditional treat. The book published a facsimile of the recipe in question, as well as sensational photos of archeological evidence.

The Truth About Hansel and Gretel caused an uproar. The media picked up the story and turned it into national news. “Book of the week? No, it’s the book of the year, and maybe the century!” proclaimed the West German tabloid Abendzeitung in November 1963. The state-owned East German Berliner Zeitung came out with the headline “Hansel and Gretel—a duo of murderers?” and asked whether this could be “a criminal case from the early capitalist era.” The news spread like wildfire not only in Germany, but abroad too. Foreign publishers, smelling a profit, began negotiating for the translation rights. School groups, some from neighboring Denmark, traveled to the Spessart woods in the states of Bavaria and Hesse to see the newly discovered foundations of the witch’s house.

As intriguing as The Truth About Hansel and Gretel might sound, however, none of it proved to be true. In fact, the book turned out to be a literary forgery concocted by Hans Traxler, a German children’s book writer and cartoonist, known for his sardonic sense of humor. “1963 marked the 100th anniversary of Jacob Grimm’s death,” says the now 90-year-old Traxler, who lives in Frankfurt, Germany. “So it was natural to dig into [the] Brothers Grimm treasure chest of fairy tales, and pick their most famous one, ‘Hansel and Gretel.’”

According to Dr. Claudia Schwabe, a fairy-tale researcher at Utah State University, the hoax was “one of the bigger ones out there, one that was done at a very sophisticated level, fooling even a lot of academics and scholars in the field.” In early 1963, Traxler read C. W. Ceram’s Gods, Graves, and Scholars: The Story of Archaeology. Published in 1949, it ignited a passion for archaeology in the imagination of the post-war world. Inspired, Traxler wrote the first draft of his own book in about a week. Then, he spent a few days on additional research at the Brothers Grimm Museum in Kassel, Germany. The museum’s director, Dr. Ludwig Denecke, kept bringing library carts with history literature to Traxler, completely oblivious to his true intentions.

Traxler’s fictional protagonist, Georg Ossegg, was a teacher and an amateur archeologist. Like the famous German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who searched for the city of Troy in an effort to prove the historical accuracy of Homer’s Iliad, Ossegg was obsessed with finding the witch’s house from “Hansel and Gretel.”

In January 1945, Traxler wrote, Ossegg evacuated together with his students to the small village of Steinau an der Straße in the German state of Hesse. There, Ossegg met a local farmer who referred to the nearby Spessart woods as the Hexenwald, or “witch’s forest,” and whose grandfather had allegedly seen a witch’s house inside. Ossegg wanted to investigate further, but with World War II over, he returned to his hometown of Prague.

In 1962, Ossegg moved to the Spessart woods once more and renewed his investigation. This time, he decided to read the text of “Hansel and Gretel” as a factual report. He set out to find the clearing where the children were abandoned by their parents. He did this by filling an eight-year-old boy’s pockets with pebbles and having him walk into the woods, dropping them along the way. (In the fairy tale, Hansel dropped pebbles to find his way back out of the forest.) But no clearing was found. When Ossegg repeated the experiment himself, he found himself in a meadow. Based on the results of the experiment, Ossegg concluded that Hansel and Gretel weren’t children, but rather adults.

Next, Ossegg decided to locate the house of the witch. After two month’s search, he found the ruins of the witch’s house and the well-preserved foundations of four baking ovens. Inside one of them, he discovered a partially charred female skeleton. Ossegg also searched for the little stable where Hansel was imprisoned by the witch, but didn’t find it. He found door hinges from the witch’s house, though, and one was forcefully broken. So Ossegg concluded that Hansel and Gretel broke into the house of the witch, killed her, and tried to burn her body.

Ossegg made his most important discovery near one of the walls of the house, where he unearthed a small tin box which contained charred lebkuchen, a bunch of baking tools, and a crumpled piece of paper, which turned out to be a recipe for lebkuchen.

Ossegg then did some linguistic analysis of the witch’s dialogue in the Grimm’s tale, and discovered that her dialect was typical for Wernigerode, a town in the state of Saxony-Anhalt. He dug into the local archives and found the so-called Wernigerode Manuscript, a parchment-bound volume describing the 1647 trial of one Katharina Schraderin, “the baker witch.”

Schraderin had invented her famous gingerbread while working in the kitchen of Quedlinburg Abbey. Another baker, named Hans Metzler, tried to marry Schraderin in order to get the recipe, but she turned him down. The rejected Metzler in turn accused Schraderin of witchcraft. After being acquitted, Schraderin fled to the woods and built a small house there. But Metzler, accompanied by his younger sister Grete, tracked Schraderin down and killed her. The siblings looked for the secret gingerbread recipe but found only a couple of lebkuchen. Metzler took them with him and tried to bake his own. He was later tried for murder, but acquitted after the judge believed his story about the cannibalistic witch. He then moved to Nuremberg, where he popularized the city’s famous lebkuchen.

Of course, none of it was true. But the 120-page book contained more than 40 photos, drawings, and models, which made the convoluted tale look quite convincing. Traxler himself posed for Ossegg, clad in a Colombo-like raincoat, a leather hat, sunglasses, fake beard, and mustache. “Photographer Peter von Tresckow and I had so much fun taking those photos that sometimes we would find ourselves lying on the ground laughing,” Traxler recalls.

Traxler admits that falsifying the so-called Wernigerode manuscript took some serious effort, but he got in the right mood by reading the 17th-century German author Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen. “Apparently, I wrote the text of the Wernigerode manuscript so well that not a single journalist or reader ever doubted it. I’m a bit proud of that today,” he says.

The truth about Hans Traxler’s literary trick came out in early 1964. (One tip-off was that Traxler copied Schraderin’s lebkuchen recipe from a Dr. Oetker cookbook.) But some people refused to accept that the book was an elaborate hoax. In the months following the publication, the publisher’s office received thousands of letters from readers demanding to know the truth: so many that they had to employ three people to answer them. Traxler and his accomplices were delighted at the reactions, but not everyone was amused. According to Der Spiegel, one indignant reader filed a complaint of fraud. The police interrogated Traxler, but didn’t press charges.

Reprinted numerous times over the years, The Truth About Hansel and Gretel has sold hundreds of thousands of copies. In 1987, it spawned a film adaptation of the same name, starring French actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as Georg Ossegg and West Berlin singer, performer, and club owner Romy Haag as the witch. While The Truth About Hansel and Gretel is still celebrated for mimicking the intellectual fashions of its time, some people still take Traxler’s tale as truth. According to Schwabe, the fervent reaction to the book says a lot. “People just love a good story,” she says. “Any discovery that promises to reveal a hidden truth or secret or mystery is enticing.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook