Why the World Overlooked Canadian Whisky

A preference for blending put the Great White North on the wrong side of industry standards.

Canadian whisky is all contradictions. It’s unknown and yet somehow incredibly popular. It’s critically dismissed but wins global whiskey awards. It’s blended, which whiskey drinkers have been indoctrinated to think means it’s inferior, yet blending is what gives it its quality. Canadian whisky is among the most fascinating liquors on the market. And yet, chances are, if you’ve bought some, you did it by accident.

“What shocked me the first time I wrote a piece about it was how big Canadian whisky was,” says Lew Bryson, a drinks writer and author of several books on whiskey. “It was like an iceberg. So much of it was below the surface, you never noticed it.”

Let’s start with the spelling. Canadians spell it “whisky,” Americans spell it “whiskey.” The former comes from Scotland, the latter from Ireland. Canada has a much larger Scottish influence than the United States does. In distillery-dotted Prince Edward Island, for example, more than 40 percent of the population claims Scottish ancestry, and Nova Scotia literally translates to “New Scotland.” Many of the country’s founding fathers—James Douglas, John A. Macdonald, Alexander Mackenzie—were either Scottish or Scottish-Canadian. In any case, the production of Canadian whisky is more similar to Scotch whisky than it is to Irish or American whiskey, so the spelling makes sense on several levels.

While American whiskey, especially bourbon, has lately carried the connotations of rural, traditional, authentic, and endemic, Canadian whisky largely doesn’t feel like any of those things. That’s probably due to the way the Canadian whisky industry began. The earliest Canadian distillers, which were founded much later than American distillers, in the 1830s or so, weren’t actually distillers, at least not primarily. Instead, they were millers. As a way to use up waste wheat, they fermented and distilled it into liquor. Canadian whisky didn’t start out with small craft distillers; it started with big companies. “It didn’t take long before spirits, whisky, became the major profit centers for these businesses,” says Davin de Kergommeaux, whose book Canadian Whisky: The New Portable Expert introduced the world of whiskey criticism to the wonders of the Great White North.

For the first century of Canadian whisky, there wasn’t really a Canadian style. Individual distillers went their own way; some were English, and a surprising number, including important ones such as J.P. Wiser’s and Hiram Walker, were American. When the American Civil War disrupted the entire American whiskey industry, Americans imported whisky from Canada, and Canadian distillers even brewed “American style” bourbons specifically for export. Soon Canadian whisky was the best-selling whisky in North America.

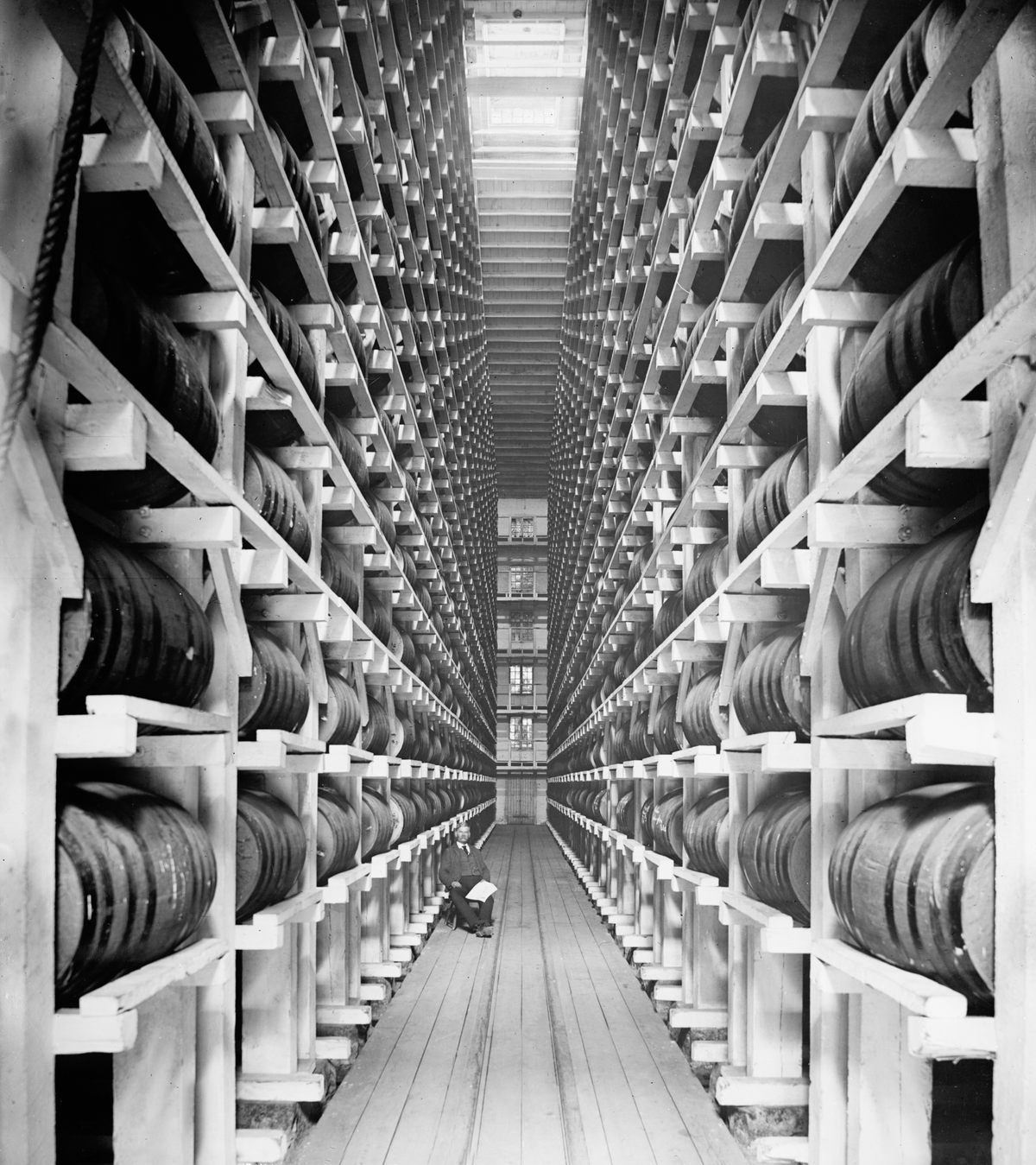

But in a continuation of the long tradition of Canada being buffeted about by whatever dumb stuff the United States was doing, the Canadian whisky industry was battered by American Prohibition. Many distillers sold for pennies on the dollar, and Canadian Club sold for less than the value of the whisky in their warehouses. A couple companies did sprout up or thrive by figuring out how to supply the bootlegging market—the Bronfman family of Montreal did it so well that they were able to buy Seagram’s, a longtime Canadian distillery, a few years before Prohibition ended.

While many American distillers and brewers returned to their pre-Prohibition recipes, Canadian whisky evolved, turning into something new. Although de Kergommeaux says there’s no documentation, and no specific date of its creation, the Bronfmans are generally credited with creating the technique of making what we now know as Canadian whisky. By the 1940s, there was a definable style, one extremely unlike American whiskey.

Unfortunately for generations of Canadian whisky distillers, that style does not fit well into existing whiskey categories, especially the ones used south of the border, in the United States, where the majority of their customers reside. The labeling of whiskey in the United States is vague, poorly delineated, sometimes misleading, and rarely helpful.

For casual whiskey drinkers, there’s a firm divide between blended whiskey and single-malt whiskey. In the United States, marketing largely from Scotch whisky makers has hammered in the message that single malt, which is made from a single type of grain in a single distillery, is fancier, better, and more expensive, and that blended is the cheap stuff. “Single malt” has a legal definition in Scotland, but not in the United States.

A number of celebrated whiskeys, such as Kentucky’s beloved bourbons, are not single malt. But they are considered “straight whiskey,” made from a mix of grains including corn, rye, wheat, and barley, with each type of straight whiskey (bourbon, rye) having requirements of how much of each kind of grain is used. Straight bourbon must be aged for a certain amount of time, but most importantly, it cannot have flavorings or colorings added: What comes out of the barrel is what you get. If you make changes to it after it comes out of the barrel, you’ll have a blended whiskey—and Scotch makers have told us that “blended” means “cheap.”

The Canadian-whisky style pioneered by the Bronfmans is neither single malt nor straight. It is, technically, blended, which, due to the particular rules of American and Scotch whiskey labeling, has a terrible reputation.

“Americans have an annoying habit of assuming that their definitions are the only definitions,” says de Kergommeaux. In the United States, a “blended whiskey” only has to contain 20 percent of “straight whiskey,” which is, you know, whiskey. In other words, American blended whiskey is often some kind of terrible neutral alcohol combined with a bit of cheap whiskey, caramel coloring, and artificial flavoring.

Canadian-style whisky is not about making fake whiskey—it’s made almost entirely from classic whiskey grains. But it’s different from straight whiskey in interesting ways.

To make American straight whiskeys, different grains are mashed together, then fermented, distilled, and aged. Canadian whisky is totally different. Instead of mashing all the grains together, Canadian distillers mash, ferment, distill, and age each type of grain separately. Then those finished whiskies are combined. That gives the blender an incredible amount of freedom—each individual grain can get individual attention.

Maybe you want to use toasted new barrels for your rye, heavily charred barrels for your corn, and very old barrels for your barley. Maybe you want to use a rye whiskey that’s been aged for a decade and a barley whiskey that’s brand new. It’s even permitted to add in up to 9.09 percent of finished other liquor. So if you want some sherry tones in your Canadian whisky, well, just add a percent or so of actual sherry. “There’s a lot more paint on the palette,” says de Kergommeaux.

Blending in Canada is about making whisky more interesting, more versatile, almost chef-like. American whiskey is like a grilled shish kabob with zucchini, chicken, bell pepper, and mushroom all on one skewer. That’s not how skewered grilling is done in, say, Turkey or Japan, where chefs recognize that each of those ingredients have their own cooking needs. Canadian whisky is taking a skewer of all zucchini, all chicken, all pepper, and all mushroom, grilling them according to each of their needs, and then combining them later. It’s not a lesser form; it might be superior.

Because the Canadian style is so much more dependent on the blender than on the distiller, it can be hard to nail down. Bourbon always tastes like bourbon; the casks used and the grain proportions combine to create a fairly universal character of vanilla and oak, on the sweet side. Canadian whisky, being so wide open, can be made in so many different ways that it’s hard to find a through-line.

Well, except for one thing: Canadian whisky almost always uses a strongly flavored rye whiskey in its mix, which gives it peppery notes; “rye” is sometimes synonymous with Canadian whisky in Canada. “The trouble with rye is that it doesn’t have much starch in it, so it produces very little alcohol,” says de Kergommeaux. “But it’s a lot more flavorful. A little bit of rye really goes a long way to contributing flavor to the whisky.” Rye is a cold-weather crop, well suited for the climate in much of Canada’s growing regions. Corn, though grown by various First Nations peoples, especially in southern Ontario, was a minor crop among those of European descent in Canada until it took off in the 1960s, whereas rye already had a substantial history in American whiskey.

Despite its guilt by association with blended whiskey, Canadian whisky has, thanks to its popularity during Prohibition, maintained a stranglehold on the American whiskey market for decades. In fact, Canadian whisky outsold bourbon in the United States from the Civil War right up until 2010. Even today, you might be shocked to learn how many top-selling whiskies in America are actually Canadian: Of the top three, Crown Royal and Fireball are both Canadian whiskies. Canadian Mist, Black Velvet, Canadian Club, and Rich & Rare are also in the top 20 in sales.

Still, Canadian whisky hasn’t fared as well in connoisseur circles. Bryson explains that a representative of Crown Royal told him that internal polling suggested that 40 percent of Crown Royal customers had no idea Crown Royal was a Canadian whisky. To even explain what Canadian whisky is, and why it’s special, is kind of a complicated task. “That’s what was really holding Canadian whisky back,” says Bryson. “People didn’t understand it, and the Canadian distillers have admitted to me that they didn’t do a great job of explaining it.”

Whiskey plummeted in popularity in the 1980s, and the modern whiskey boom only really started around the early 2000s. Bourbon, Scotch, and even Irish whiskies experienced a massive increase in sales and stature during the last two decades. “The Canadians were probably the last ones to that dance,” says Bryson. Only in the past couple of years has Canadian whisky begun to receive the attention it’s always deserved. In 2016, Jim Murray’s influential Whisky Bible named Crown Royal’s Northern Harvest Rye the whisky of the year. It was interpreted as almost a protest award, given to start the conversation about the value and quality of Canadian whisky.

Since then, most international contests have added a category for best Canadian whisky, alongside Scotch, Irish, bourbon, and others. It’s one of the most exciting categories in all of alcohol: By its nature, it’s encouraged to be wild, experimental, unpredictable. And due to its long reputation as bottom-of-the-shelf “blended” whiskey, even now it’s usually an outrageously good bargain. That 2016 winner sells for about $45. On the super high end, Bryson says, 42-year-old Canadian Club is similar in quality to a 40-year-old Glenfiddich. The Glenfiddich costs $4,500 for a bottle. The Canadian Club? $300.

Canadian whisky has been here all along, fascinating and wildly but quietly successful. It doesn’t demand your attention, but it deserves it.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook