During Prohibition, Federal Chemists Used Poison to Stop Bootlegging

They tried to make industrial alcohol too lethal to drink.

On January 15, 1922, the New York Times reported that 35-year-old Robert Doyle, a veteran of World War One, was found blinded and afraid in his rooming house on West 23rd Street. A doctor conveyed Doyle to the hospital, where he died six hours later. The paper also reported the death of another local man—he had brought alcohol home from his workplace to add to his coffee. The problem was that America was in the midst of Prohibition, and he had worked at a furniture-polishing company. Both men had drunk a fatal dose of wood, or methyl, alcohol.

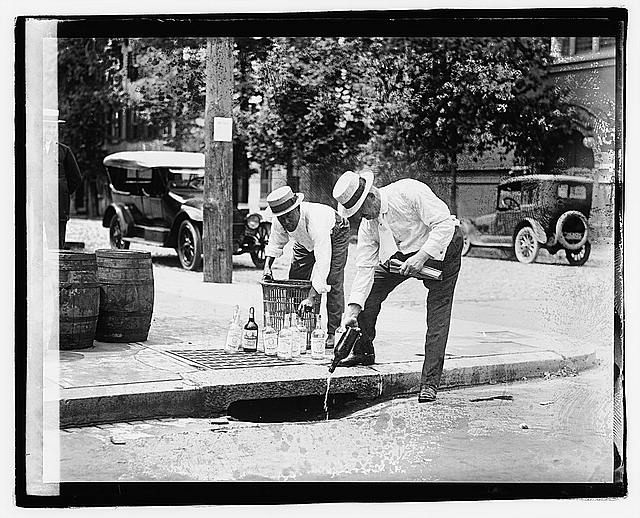

These deaths were part of an epidemic of alcohol poisonings that swept the country after the United States made the manufacture and sale of alcohol illegal in 1919. An illicit alcohol industry boomed, and despite increased border security, alcohol flowed in from Mexico and Canada. But some bootleggers, eager to cash in on black market prices, wanted to sell alcohol made closer to home. The government could ban the brewing of beer, but not the production of industrial alcohol, which was used to make everything from perfume to paint. So when bootleggers redistilled industrial alcohol to make it drinkable, the federal government responded by requiring manufacturers to add in increasing amounts of poison.

Doyle was an early casualty of the resulting showdown between federal chemists, who tried to make the country’s industrial alcohol deadly to drink, and speakeasies’ and bootleggers’ chemists, who tried to remove the poisons. The Times article describing Doyle’s death noted that an unnamed but “prominent” local club had employed a chemist to double-check that patrons’ booze was safe to drink. The problem, reported the anonymous writer, was that much of the liquor flowing into speakeasies hadn’t been brewed abroad, but was in fact “denatured” industrial alcohol.

Manufacturers had been adding poison to industrial alcohol in America for decades. In 1906, Congress passed a law decreeing that industrial alcohol was exempt from taxes, provided that enough toxic additives made it undrinkable. The government also configured dozens of official formulas for denaturing alcohol to make it poisonous. But during Prohibition, well-paid chemists working for bootleggers soon found that boiling industrial alcohol in stills evaporated most of the poison. However, they also discovered that it was often impossible to remove it all.

The results were deadly. Bootleggers sold the treated alcohol, and newspapers kept tallies of Americans suspected of dying from poisonous liquor. Often, victims were working-class or poor—people who couldn’t afford smuggled beer or whiskey. But anti-Prohibition activists were sure of one thing: The National Prohibition Act, which had been ratified to halt alcohol’s negative impact on society, was the cause.

Chemists with criminal leanings found ready employment during Prohibition. Deborah Blum, author of The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York, writes that the easiest alcohol to convert was Formula 39b—it was mild, intended for perfumes and cosmetics, and “renatured” almost perfectly into entirely drinkable liquor. As the federal government introduced formula after formula, chemists managed to distill out the danger. According to Blum, by 1926, the federal government had retired three formulas entirely, since bootlegger chemists had gotten so good at distilling them away. A former administrator remembered raiding illicit distilleries and finding advanced chemistry setups on site.

By Christmas 1926, it was impossible to ignore the crisis. In New York alone, dozens of people died from drinking during holiday festivities. On the cusp of that shocking death toll, the federal government announced a requirement to add twice as much methanol, which was deadly and impossible to filter out. But officials also ordered the addition of benzine and oxidized kerosene, in order to increase the alcohol’s foul smell. This would become known as “Formula 5,” and it was rumored that three drinks containing the mix would result in blindness or death. Despite the increased danger, proponents believed that its noxious aroma would warn people away. The greatest cheerleader of poisoned liquor was Wayne B. Wheeler, the general counsel of the Anti-Saloon League, who frequently stated that people poisoned by alcohol were committing suicide.

That attitude was widespread. To many “dry” activists, the idea that people would still drink despite the danger was baffling. But others denounced the policy. Senator Edward Edwards from New Jersey accused both Wheeler and the federal government of “legalized murder.”

In April 1927, Popular Science magazine attempted to explain the furor. “Uncle Sam has been on trial before the bar of public opinion,” observed writer Dr. Frederic Damrau, “charged for no less a crime than willful and premeditated murder.” Damrau weighed the opinions of both sides, before stating that “the alcohol is made poisonous not with the idea of killing drinkers, but because the only known unremovable denaturant happens to be poisonous.” Federal chemists, meanwhile, were working to develop a noxious but non-lethal substance that could not be removed.

In 1930, they announced that they had found one: alcotate, a petroleum byproduct. With its sulfurous odor of garlic and rotten eggs, it would make drinkers violently ill without poisoning them. But by then, bootleggers had shifted to brewing their own hooch from yeast, water and sugar. According to Blum, an estimated 10,000 people may have died during Prohibition from federal denaturing requirements: a gruesome death toll for a program intended to help people.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook