The Uncertain Future of a Border-Straddling Liquor

Sotol could bring Texans and Mexicans together, or divide them.

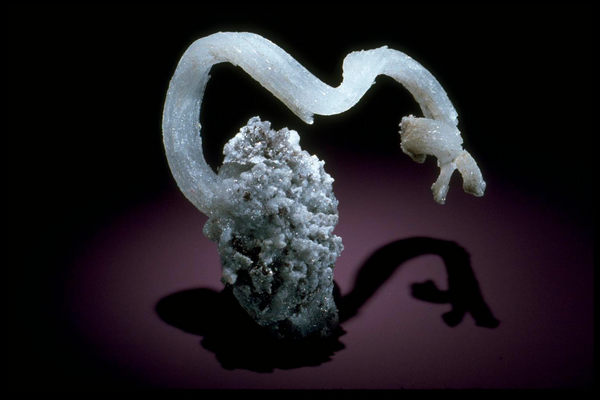

Brent Looby of Desert Door Distillery wants to share sotol with the world. “It’s a gateway to West Texas,” he writes, “that tastes unquestionably of the Texas land.” The spirit is distilled from dasylirion, a spiky succulent that dots the arid terrain of the Chihuahuan Desert, which spans the U.S.–Mexico border. In Texas, they call it “desert spoon.” Desert Door is the first commercial sotol distillery in the United States.

The venture has some detractors.

“It’s an appropriation that should be dealt with,” says Jacob Jacquez, the sixth-generation sotolero, or sotol distiller, behind Sotol Don Celso in Janos, Mexico. The company is named for his late father, a sotolero and politician who defended the niche spirit which, for much of the 1900s, was outlawed and violently suppressed. “I think they should take a step back and respect the families that were persecuted, that fought for that word: ‘sotol.’”

This transnational debate within the craft community now has advocates in the U.S. and Mexican governments. The USMCA, a trade deal signed by President Trump last week to replace NAFTA, includes a provision that may classify sotol as distinctively Mexican. In other words, Texan sotol distillers like Looby could be—like Californians who make “sparkling wine” rather than champagne—barred from using the word.

On a deeply fraught border, a storied spirit stands to either bridge the divide or deepen it.

Long before European contact, Rarámuri tribes of the Chihuahuan Desert fermented juice from sotol into something of a low-alcohol beer. But in the 1500s, Spanish distillation techniques presented new possibilities for the desert shrub.

“It’s a transparent plant,” says Ricardo Pico, founder of Sotol Clande, a cooperative of five vinatas, or sotol distilleries, throughout Chihuahua. “It tastes like where it comes from.” The plant’s acute terroir made it a staple of rural life among the people of Coahuila, Durango, and Chihuahua, an enduring link between Mexicans and Mexico itself—the land made liquid. “In dry areas, it’s like rain on the dessert: some earthiness, a peppery finish. In the forest region, there’s moss, eucalyptus, menthol—just like going to the forest,” says Pico.

Looby claims that the earliest known traces of human consumption of sotol, however, are found in Texas. “Indigenous people have been cooking and consuming sotol [here] for 10,000 years.” To boot, he adds, sotol was first commercially distilled in El Paso, in 1907, because it was illegal to distill sotol in Mexico until 1994.

There’s certainly some truth to that claim. Throughout the mid 1900s, Mexican police implemented a broad ban on sotol. Experts disagree on the reason—it may have been tequila producers stifling competition, or simply the Mexican government’s puritanical approach to DIY distillation, as sotol was often produced in the home. Still others claim it was the Mafia clearing the market for corn whiskey during U.S. Prohibition. Whatever the reason, while sotol led a quiet life in West Texas, Mexican police made a burnt, bloody scene of it south of the border.

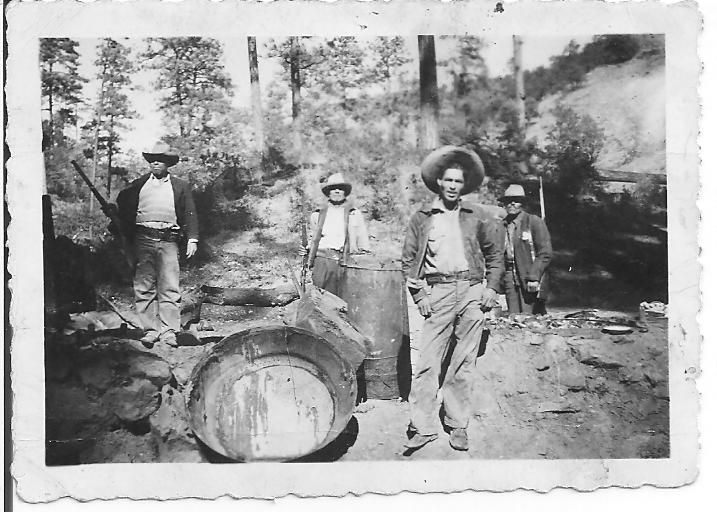

During American Prohibition, Mexican police sought to rid the country’s northern fringes of sotoleros and their vinatas. “My great-grandfather was kidnapped by the state police,” says Jacquez. For him, the perceived role of the United States isn’t easily forgotten. “My people were persecuted during your Prohibition because of the drink,” he says.

Branded as outlaws, sotoleros mobilized their distilleries by latching their copper stills to donkeys. “They couldn’t catch them all red-handed,” says Juan Pablo Carvajal, co-founder of Los Magos Sotol. “Someone would always tip them off.” Police burned down vinatas and riddled heirloom copper stills with bullets, arresting and even killing sotoleros. Jacquez says most of his uncles became teachers, farmers, or carpenters. “You couldn’t make sotol; you might get shot.” Even after Prohibition ended, the Mexican government smeared the spirit as field-worker swill fit for bandits and low-lives.

“That’s what we’re bouncing back from now,” says Jacquez. In the 1980s, sotoleros, including, prominently, Jacquez’s late father, petitioned local and state governments to earn their rights back. In 1994, the Mexican government officially issued licenses to distill sotol, and, in the early 2000s, the spirit earned protected status under a Denomination of Origin. “It was a victory, because we were finally on the map amongst Mexicans, at least,” says Jacquez. Today, sotol is following the path to global recognition paved by tequila and mezcal.

Twenty-seven countries recognize sotol’s protected status. The United States is not one of them.

The United States’ first sotol distillery started when Looby and his co-founders, Judson Kauffman and Ryan Campbell, were tasked with designing a business during a “Venture Creation Course” at the University of Texas at Austin. “When Judson was young, his uncle talked about sotol being moonshined out in west Texas where he grew up,” Looby writes. “We are attempting to tell another side of the story that has been overlooked for some time.” Their theoretical distillery won first place in a class competition, and in 2017, they founded Desert Door Distillery. Today, they employ 40 people across six U.S. cities.

With access to 75,000 acres of West Texan property littered with “desert spoon,” the Texans can afford to experiment. They age a portion of their sotol in oak barrels, leaving the product tasting similar to a cognac or bourbon. They partnered with a local brewery to craft the world’s first sotol-aged beer. You can buy branded beanies, totes, and keychains on their website.

While Desert Door has faced criticism, they remain confident in their mission. “We’re a huge state with a lot of pride,” Kauffman told The Statesman. “We should have something to call our own.”

Texas’s second distillery took a different tack. Morgan Weber and other co-founders from Marfa Spirits crossed the border to learn from sotoleros before launching their business. “I figured if I just go into this blind, I stand a strong chance of pissing somebody off without knowing it,” he told me. He consulted with producers and distributors, and attended a sotol conference in Chihuahua hosted by sotoleros. Despite them being the only three non-Spanish speakers, their hosts hired a translator to keep them up to speed. “We all want to pay homage to the spirit,” says Weber, though he understands the backlash among hard-line never-Texans. “They’re completely in the right to feel that way, but I hope that they keep an open mind.”

South of the border, news of American sotol distilleries is met with mixed reviews, at best. Carvajal sees acceptance falling along generational lines: “All the new people who are coming into the industry see this as an opportunity to grow, but most of the old-school sotoleros don’t want the U.S. to be making sotol.”

For some, it’s the role the U.S. may have played that grates. “I see producers calling it ‘Texas sotol,’’’ says Jacquez. “I think they should change the name. Play a fair game.”

“Would I make sparkling white wine in Chihuahua and call it ‘champagne?’” says Pico. “It’s not my thing, not my heritage, not my tradition.” He suggests Texans use the name “desert spoon spirit.” “It’s not a bad name.”

With the passage of a new North American trade deal, it’s a name Texas distillers may have to learn to love. A minor provision commits the U.S. to consider classifying sotol as distinctively Mexican. Despite its vague wording, the measure found some fans in Mexico.

“It’s a good call,” says Pico. “You can’t put plans that have just been made in the same jar as hundreds of years of tradition. We’re not talking about the same thing.” He and others feel the recognition is not only a symbolic victory, but one that will bolster a regional economy and a tradition long suppressed.

Desert Door’s founders are not losing sleep. “The USMCA is under no obligation to reach a particular conclusion,” writes Looby. In short order, the company amassed a bipartisan group of 20 lawmakers willing to fight for sotol’s binational identity. Texas Senator John Cornyn raised the issue in a Senate Finance Committee hearing last month, along with a rave review. “For those members of the committee who’ve never consumed sotol, I would recommend it,” he said.

Carvajal appreciates the symbolism of the trade deal, but worries about missing an opportunity to broaden the sotol market. “I think the Mexican government wants to protect the citizens in this industry,” he says. “But it would grow stronger if we allowed other people to join in on the tradition, if the land that they live on allows it.”

Through its violent history, and its dogged plod into modernity, Carvajal sees, more than anything, a shot at reconciliation. What if there were a regional Chihuahuan Desert denomination of origin? “It would be a great statement to show that we share a common land,” he says, “that we share some traditions, and some ideas of what we can do with that land.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook