The Rise and Fall of North Carolina’s National Hollerin’ Contest

Hollers are sort of like the yodels of the American South.

In the summer of 1952, a young graduate student named Ray B. Browne left the University of California, Los Angeles, to conduct folkloric research in rural Alabama. Farmers there told Browne that a few decades earlier, you couldn’t stand outside your barn without hearing half a dozen farmers hollerin’ at each other across the fields. Browne, who later became famous for pioneering the study of pop culture at the university level, chronicled his trip in A Journal of American Folklore, where he wrote that the “holler” was both functional and expressive, almost like a Alpine yodel. He described it as “a spontaneous overflow of the poetic urge.”

A holler is any nonverbal communication produced by the human voice. Before the advent of phones and electricity, rural dwellers used these sounds to greet one another, send messages, or communicate danger over long distances. One can find examples of hollerin’ in communities around the world, but one region where the cultural importance of hollerin’ has endured into the modern era is the American South. One town in Sampson County, North Carolina, even hosted a hollerin’ contest for 40 years.

Ray Browne posited that this robust hollerin’ tradition may have originated with the South’s enslaved population. White residents of Alabama used a racist pejorative for Black people when they described hollers, though Browne didn’t find any Black residents who said they hollered. According to former contest winner Robby Goodman, the practice may have gone back even further, to Native Americans. In a documentary about the contest, Goodman points out that Indigenous people communicated nonverbally long before Europeans showed up; the same documentary shows members of the local Coharie Tribe at the contest drumming, dancing, and vocalizing in traditional dress.

The sandy, agricultural lands of Sampson County boast their own distinctive holler, consisting “primarily of rapid shifts between natural and falsetto voice within a limited gapped scale,” according to the liner notes of Hollerin’, a 1970s album that showcased contest winners. But sources disagree about the origin story for this particular holler. The liner notes say it came from English-speaking settlers in the 1700s, when men on rafts would holler at each other to avoid collisions while transporting logs down to the coast. But the ethnomusicologist Dave Evans points out in the Journal of American Folklore that many Sampson County hollers feature alternation between a falsetto and natural voice, a technique that’s common in some African cultures—an observation that raises questions about whether the Sampson County holler also has roots in Black communities.

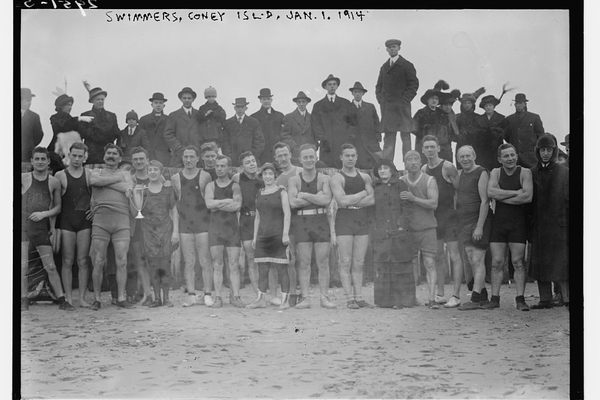

By the mid-20th century, hollerin’ was on the decline, thanks to modern conveniences and—according to Browne—the stigma associated with rural poverty. Hollerin’ was fading as a practical tool, but it was about to see its heyday as an art form. The contest was founded in 1969, at a time when North Carolina was still in the process of court-ordered desegregation. It started when the town of Spivey’s Corner decided to host a National Hollerin’ Contest to raise money for its volunteer fire department. Historical photographs show enthusiastic crowds of white Southerners watching as contestants stood on stage with a microphone. At the contest’s apex, tens of thousands flocked to the town to hear hollerers try to win fame and glory. Some of the hollerin’ champions even ended up on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

But as the 20th century wore down and the 21st began, interest in the contest dwindled, until Spivey’s Corner announced in 2016 that it was shutting it down for good.

“In the 1970s, you weren’t as far removed from hollerin’ being a way of life,” Brian Gersten, the filmmaker who documented the contest in its final days, tells me. “Now, it’s that much more removed from people doing this as a means of communication. Part of it is that [practitioners] have died out, and part of it is that younger generations flock to cities, and it’s not a tradition that’s really been passed down.”

Even in these waning days of the holler, former contestants still recall the passion, fun, and artistry that went along with it. Sheila Frye, a Sampson County native with blonde hair and a clear, robust holler, was never interested in the contest as a kid. But in 2002, Frye and her husband saw one of the hollerin’ contestants on David Letterman, and Frye’s husband suggested that she think about entering. She did—and she started winning.

“I had one particular holler that I actually used when I was growing up. I called it my ‘across the branch holler,’ a greeting holler to my aunt,” says Frye, who ended up winning the ladies’ division 10 times. In the contest, Frye aimed to emphasize the role of women on rural farms in Sampson County decades ago.

Contest judges broke hollers down into four distinct types. First was the communicative holler. “It’s been said that some farmers got up in the morning to hitch up their mule, and would let a little hoop out so another farmer would hear, oh, Farmer Joe’s up and feeling good! And if he didn’t hear it, he might think, maybe there’s something wrong at Farmer Joe’s house,” Frye tells me.

Then there was the functional holler. “As the old saying goes, you’d get turned about in the huckleberry woods,” she goes on. “You’d start hollerin’ to the farmhouse and wait for someone to holler back, and you could find your way out of the woods.”

The third was the distress holler, which a farmer might use to call a midwife. Finally, there was the expressive holler, which was just for fun. “You have to remember, you didn’t just get in the car and go to the movies,” Frye says. “Sometimes you had to entertain yourself! In the evening when the chores were done, the wind was down, people would go out and do hollers.”

The judges typically preferred Southern-style, person-to-person hollers. One year, according to the New York Times, the yodels of a mountain climber from England lost out to the hollers of a local corn and tobacco farmer. The first year that Sampson County native Tony Peacock competed, he chose a kind of holler that his father once used for hog-calling. He didn’t realize that the judges wanted to hear human-to-human hollers.

Like Frye, Peacock didn’t attend the contest as a child, but hollerin’ ran in his family: His first cousin, Larry Jackson, was the first person ever to win the contest nine times. In 1998, his first year competing, Peacock didn’t place, but Jackson took him aside to reassure him: “You got a good set of lungs. You should come back. Just don’t call the hogs this time!” Peacock modeled his new hollers on the calls of Baptist preachers and tobacco auctioneers, and ended up winning the contest six times.

Several of these former contestants have tried to keep the hollerin’ tradition alive. When the contest ended in 2016, Robby Goodman tried to bring it back as the World Heritage Hollerin’ Festival, but Hurricane Matthew swept through the state and derailed plans. For his part, Peacock now visits schools throughout North Carolina to teach narrative writing, and he always makes sure to mention hollerin’ to the schoolkids. On the last day of his visits, Peacock takes his classes outside and demonstrates each of the four kinds of hollers, then leads a call-and-response holler.

“Although hollerin’ is not something that we need practically, it’s a way to appreciate our past and a lot of our modern conveniences,” Peacock likes to tell them.

The holler might be fading from history—yet they still crop up now and then. Earlier this year, I was with a park ranger in rural Tennessee. As we approached a house whose owner doesn’t have a telephone or email, the park ranger let out a high-pitched wallop of a sound, alerting the man inside to our presence: a real-life holler, right there in the wild, reverberating through the greenery of the American South.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook