How the 1985 Fantasy Film ‘Legend’ Ended Up With 2 Soundtracks

Your favorite probably depends on where you grew up.

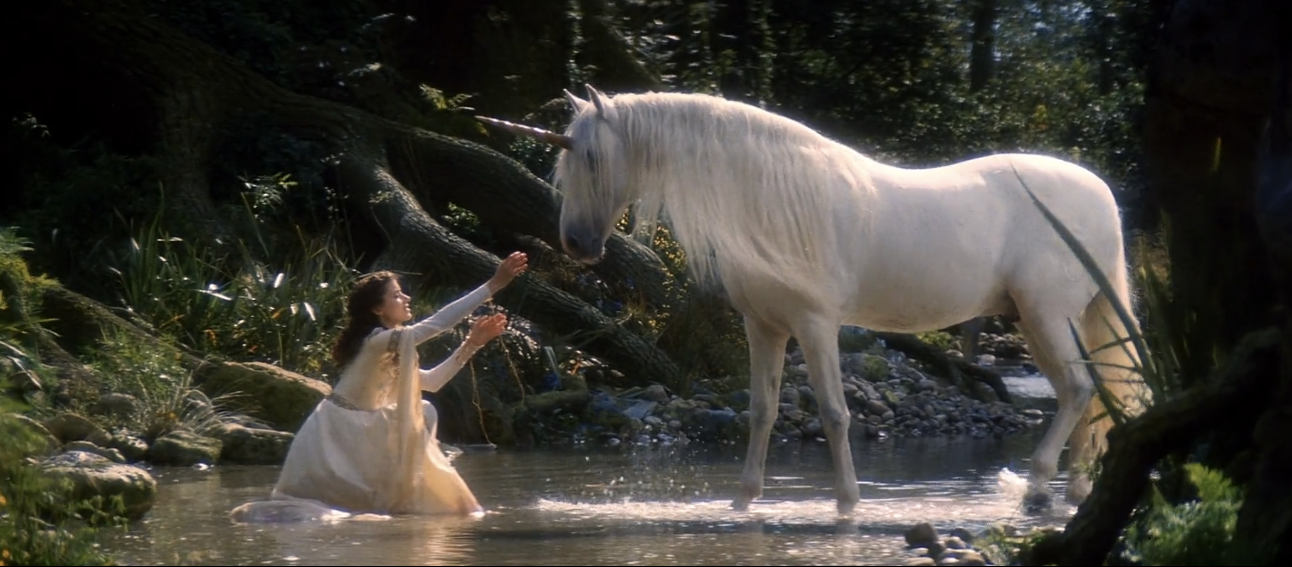

Darkness calls. (Photo: Screenshot by Eric Grundhauser)

Ridley Scott’s 1985 fantasy classic Legend is a beloved ’80s movie, unless you don’t like it. For every ’80s kid that marks it as one of the seminal films of their childhood, full of whimsy, excitement, and incredible effects, there is a film buff who will criticize the movie for being boring, poorly edited, or incomprehensible.

But possibly even more heated is the debate over the film’s two soundtracks, which themselves are related to the rocky history of the film. “If you’ll excuse the term, it’s legendary,” says Kristen Romanelli, Managing Editor for Film Score Monthly, who, when approached about the subject, was instantly familiar with the dueling soundtracks.

As a child of the ’80s Romanelli grew up believing the soundtrack to Legend was by German electronic music group Tangerine Dream. Then came a startling revelation: “When I went to college, I learned that there was a completely different cut of this film with a completely different score.”

For those who have never experienced the magic/trainwreck of Legend, the film revolves around Jack and Lili, a pair of young lovers, played by Tom Cruise and Mia Sara respectively. They struggle against the Lord of Darkness, played by a never-better Tim Curry, covered in head-to-toe devil make-up (only fools debate his performance in the film).

Also, there are unicorns, which play a large or small role depending on which cut of the film you are familiar with. The plot, admittedly scant, revolves around the Lord of Darkness corrupting the pure Lili after his hench-goblins manage to steal a unicorn’s horn. Jack, a near-mute child of the forest, must then travel to Darkness’ fortress and rescue Lili with the help of some friendly fairyfolk. The film maintains an air of fantasy and ethereal mystery throughout, some of which is by design, and some of which is thanks to some confusing editing by notorious tinkerer Scott.

Then there is the music. Scott’s original choice to score the film was industry veteran and film score legend Jerry Goldsmith, who had provided the scores for films like The Omen, Poltergeist, Gremlins, and even Scott’s Alien. Goldsmith was brought on early in the production process, and began writing songs that would be sung by the characters in the film, tying his vision of the movie’s music very closely to the narrative. He spent six months composing the final score for the movie.

In a 1986 article in the Washington Post, Goldsmith described the score as “the best score I’ve ever done, and people who have heard it have felt it was an outstanding score.” For the most part, his score maintained a classically fantasy movie feel, but it was also interspersed with oddly modern flourishes. For example, a jaunty run of flutes, horns, chimes, and choral voices could be interrupted with a bolt of twangy synth sound. “If you listen to the structure of the score, a lot of it is very postmodern and Stravinsky-esque,” says Romanelli.

Unfortunately, for all the positive reactions Goldsmith’s score reportedly received internally, it didn’t seem to play well with audiences. After screening for European test audiences, a preview screening in San Diego concluded with dismaying results: younger viewers were unable to take the fantasy film seriously. This shook both the producers’ and Scott’s faith in the film as it was. In response, Scott made major edits to the film.

A European cut of the film was produced, maintaining an edited version of Goldsmith’s score, as well as an American cut which contained an entirely new soundtrack. “Not only do they have a new soundtrack brought in, they re-edit the film, and it’s almost a completely different story,” says Romanelli.“Language is changed. Instead of a ‘Princess,’ Lili is referred to as ‘Lady,’ and the focus is more on her and Jack, and rescuing Lili, instead of the unicorn, which is more the focus of the European cut.”

To give the movie a score that might resonate more closely with younger viewers, the production brought in German New Age synth band Tangerine Dream. The band had previously scored movies including Firestarter, and even Risky Business, using their signature ethereal synths. Unlike Goldsmith’s score, which was tightly tied to each beat of the film, Tangerine Dream’s score was more rangy, and loosely atmospheric. The Tangerine Dream soundtrack sounded quite clearly like a Tangerine Dream soundtrack.

Of course, back in 1985, when the film was released, the fact that there were alternate versions of the film playing in different parts of the world—each with a wildly different soundtrack—was not common knowledge. American audiences simply experienced the film through the sound of Tangerine Dream, while European viewers came to know a version of Goldsmith’s score.

While Tangerine Dream seemed happy with their work, Goldsmith was less than impressed with the replacement of his score. In that same Washington Post article, he says, “It came as a total surprise and shock to me,” and later states, rather diplomatically, “That this dreamy, bucolic setting is suddenly to be scored by a techno-pop group seems sort of strange to me.”

The film received mixed reviews upon its release, with most critics praising the make-up, but faulting the movie for its directionless plot. Roger Ebert’s review said, “All of the special effects in the world, and all of the great makeup, and all of the great Muppet creatures can’t save a movie that has no clear idea of its own mission and no joy in its own accomplishment.” Even today, the movie only holds a 48 percent “Freshness Rating” on Rotten Tomatoes.

But nonetheless, in the years since its release, the movie gained a strong cult following. With the rise of the internet, American viewers who had grown up with the Tangerine Dream version were eventually able to get their hands on the Goldsmith version, and vice-versa. A director’s cut of the film was released in 2002, using Goldsmith’s score, and bringing a third version of the soundtrack into the mix. Still elusive, however, is the original preview cut of Goldsmith’s full score, which is mainly available as a bootleg.

In the years since Legend’s release, its two soundtracks have also garnered fandoms of their own, with vigorous proponents on either side of the debate arguing over forums and in reviews (for an exhaustive, academic reading of both soundtracks, see here). When asked to chat for the article, Romanelli and some of her peers at Film Score Monthly immediately had thoughts on which score was superior: Goldsmith’s.

“Everyone has a quick opinion on this,” says Romanelli, “I feel like a lot of people bring this down to a synth vs. orchestral thing, but that’s absolutely not true. […] I think it’s a lot more complex than the traditional vs. 80s pop.” Goldsmith, a virtuoso composer from a more traditional background, is often thought to have made the more complex and detailed score, while Tangerine Dream’s score is praised for its originality and otherworldly vibe.

But ultimately, Romanelli says, the deciding factor in which score is superior boils down to context, stating simply, “The Goldsmith score would not work on top of the United States cut, and the Tangerine Dream score would not work on top of the European cut.”

If you’d like to decide for yourself, both soundtracks are available in multiple releases online. If you still can’t decide, you could always vote for option three: Reggie Watts’ live, improvised soundtrack to the film.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook