How the Hidden Sounds of Horror Movie Soundtracks Freak You Out

From altered voices to “infrasound,” these audio tricks spook and unsettle.

You’re sitting in the movie theater; it’s pitch black except for the dim glow on-screen. Nothing scary has happened yet—but you see a person walking, alone. You feel an overwhelming sense of dread. A slow, growing hum murrs over footsteps, and you know the person isn’t safe. You, perhaps, feel you aren’t safe watching.

You wait for the inevitable conclusion, fixed on what you might see, listening for the cue that a killer or monster is ready to attack—though nothing on screen hints at this. The source for your anxiety is elusive, but it was carefully crafted through hidden audible elements that play on human emotions, causing your hairs to stand on end. This is the brilliance of what music does in a horror film.

The way composers make the most out of their musical tools to induce fear is both an art form and a science. Since horror movies rely on music, movie score composers carefully consider how to use familiar sounds in unusual ways; this distortion of reality unsettles us even if what we’re hearing is, in many ways, obscured.

“The sound itself could be created by an instrument that one would normally be able to identify, but is either processed, or performed in such a way as to hide the actual instrument,” says Harry Manfredini, whose music score for Friday the 13th was cemented in the thrasher film genre of the 1980s.

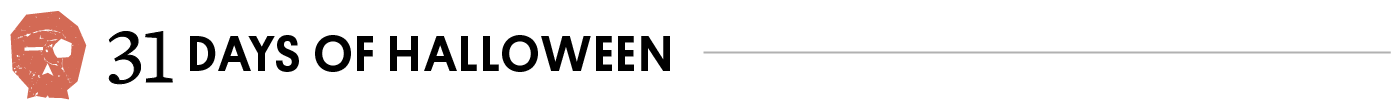

The sounds that do this to us aren’t always unusual; but their deep rumblings or high-pitched squeals signal danger almost (if not actually) instinctively. Distressed animal calls, women screaming and other nonlinear sounds, which are irregular noises with large wavelengths often found in nature, were used in The Shining and other movies to create an instinctual fear response, as recorded in the test subjects of a 2011 study at the University of California. Often these sounds are buried in the complex movie score or, sometimes, as subtle sound waves that give an adrenaline rush like a mini, internal roller coaster.

Taking a sound out of one normal context and then placing it into a new, scarier one can do this. While some of these sounds are subtle, others stick out so much they become characters themselves. People who have seen Friday the 13th learned that a specific sound (a human vocal noise described as “ki ki ki ma ma ma” by Manfredini) means that the killer, Jason Voorhees, is lurking nearby with his machete, even if he isn’t shown on screen. Just knowing that Jason might be in the room with us heightens our senses, and even though the sound is vocal, it’s unlike one any that a person would normally make. When Jason’s sound is isolated, you hear breathiness in an echo; but the surrounding music and bloody visuals work together, bringing the noise to a functionally creepy place.

One unsettling and hidden “sound” that is given credit for freaking out an audience is infrasound—a low-frequency sound that cannot be heard, but literally unsettles human beings down to our bones. Infrasound, which exists at 19 Hz and below, can be felt, but human ears begin to hear sound at 20 Hz. Infrasound exists in nature, and is created by wind, earthquakes, avalanches, and used by elephants to communicate over long distances. At a high enough volume, it may be possible for humans to perceive sound as low as 12 Hz, but even common objects can emit infrasound, something some horror movie music composers use to their advantage.

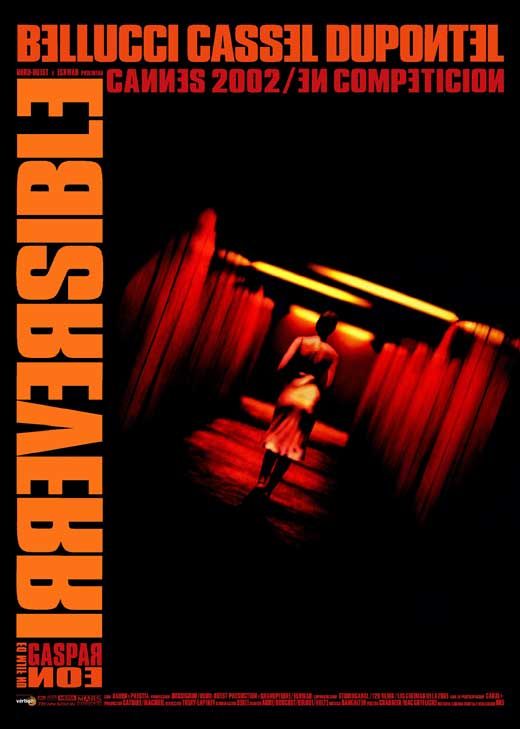

Filmmaker Gaspar Noe admitted in an interview that he intentionally used sound that registered at only 27 Hz, just above the 20 Hz limit for infrasound, in his 2002 film Irreversible. The movie is technically an avant-garde thriller, rather than classic horror—but the intense violence, raw camera angles and disturbing images and content have made it dip into the horror movie category. The characters embody the monster-side of human behavior and indulge; you’re bombarded with disturbing images of sexual violence, which understandably caused controversy, and the soundtrack intensifies this.

“You can’t hear it, but it makes you shake,” Noe told Salon. “In a good theater with a subwoofer, you may be more scared by the sound than by what’s happening on the screen.” In Irreversible, deep rumblings and a swaying, otherworldly grinding sound increases in volume, causing the viewer to feel dread just before extremely disturbing imagery begins. The 2002 movie Paranormal Activity was also rumored to use infrasound, though even if the deep rumblings in the film are above the 20 Hz threshold, they seemed to to a good job of unsettling audiences anyway.

Steve Goodman, in Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear, says that while the ways sound in media cause these responses in human perception are under-theorized, it likely has its place, especially with a source-less vibration like infrasound. “Abstract sensations cause anxiety due to the very absence of an object or cause,” he writes. “Without either, the imagination produces one, which can be more frightening than the reality.”

Sometimes using altered noises from everyday objects to get an infrasound-like effect can even save on production costs. Christian Stella, who mixed the score of the 2012 zombie film The Battery on a low budget, revealed on Reddit that he “ended up using recordings of power transformers, air conditioners, etc, that I modulated to make deeper.” Another part of the production team layered music on top of this to create the full movie score.

To manipulate the audience, Manfredini’s process begins with viewing a complete or at least near-complete film. To help the visual narrative along, he remembers the actions, objects or colors that reappear and creates audial themes around the visuals. Later, he overlays tones, rhythms and stand-out sounds to evoke something we’ve seen, sometimes using sounds as cues, to drive home the otherworldly narrative we find ourselves in while we clutch our seats. In a sense, he’s fooling the audience into believing that what we’re seeing is logical to the story we’re immersed in, and that we drew that conclusion first.

When he sees a scene where he thinks a special effect sound would work best, he works with the sound effects artist; then, he balances the effect sound with his score. “If his sound is a low sound, I might go high, and vice versa. Visually if I see something very large the logical choice would be a low sound, and if it is small, a high one,” Manfredini says. This is a departure from the horror movies of the 1940s and ‘50s, which relied on orchestral scores to fill in the silence. Horror movies today are more atmospheric, making the movie seem more plausible and causing a more direct sense of danger.

When we watch horror movies, we’re not meant to be simple spectators; we become passive participants. While immersed, we become convinced on some level that we’re there with the characters, walking around a dark corner or opening a door to a place we are definitely not meant to be. We might be safe in our living room while the monster approaches in the shadows, but the movie makes us believe otherwise. It’s just a trick of the ear, though, obviously. Hopefully.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook