In Search of the Origins of Native American Grave Houses in Oklahoma

Indigenous cultural knowledge is closely guarded for a reason.

The house is haunted, but not in the way you might think.

In a number of quiet family cemeteries in Oklahoma, grave houses or spirit houses, as they are known, dot the landscape: little, physical manifestations of tradition, heritage, family, and grief. Some of these miniature houses are new, made of fresh two-by-fours and with simple thatched roofs, others are so old that they appear rough hewn, from decay and exposure. Some are large and imposing, with two stories and intricate doorways. Some are so small that there is no question who they belong to.

The idea of the grave house is simple: A structure built over a grave to serve as a home for the spirit. No matter their design, these houses also evoke Indigenous resilience and show how colonization transforms tradition.

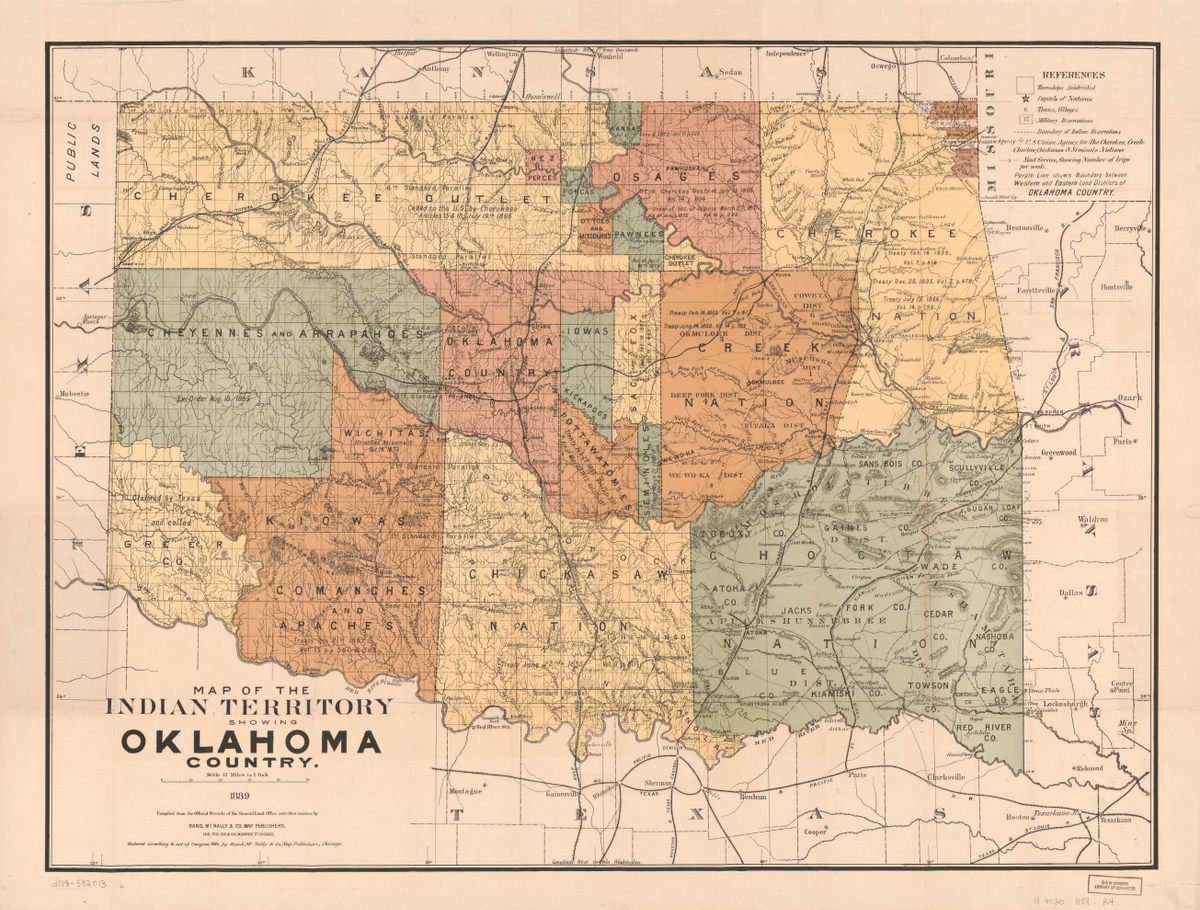

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act, which granted him the authority to relocate, no matter how painfully, tribes ancestrally connected to Southern states to lands west of the Mississippi. The Cherokee call this forced removal nunna dual tsuny, which roughly translates to “Trail of Tears.” The name persists, though the tribe was not the only group affected by the state-sanctioned violence. Scholars don’t conclusively agree how many lives were lost among the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole people during this specific time period, but the number is thought to be upward of 10,000. The Chickasaw, too, have their own Trail of Tears. In addition to these five tribes, known as the Five Civilized Tribes, there were smaller communities whose names are lost to time, that also experienced a large loss of culture and lives.

Before, tribe members were buried beneath the home so that the spirit remained in residence with loved ones. Sources differ on when the shift to separate houses for the dead began, but it’s thought to be associated with that forced relocation—perhaps during the removal, on the trail, or when the traumatized tribes resettled in what was then called Indian Territory, now Arkansas and Oklahoma.

This uncertainty is a recurring problem in the study of Native American tradition. Though Indigenous scholars, historians, and others have done extraordinary work piecing together the history of that time, through passed-down stories and archaeological excavation, the scars of the loss of cultural memory and knowledge run deep.

To learn more about grave houses, part of my own heritage as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, and to get at their connection with the Trail of Tears, I sought out Melissa Harjo-Moffer. She is the archives and records technician for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Oklahoma, and she collects and preserves items related to its history, including genealogical records. She’s also fluent in the Muscogee (Creek) language. She started working for the Nation in 2004 as a secretary and worked her way through a variety of roles until she found the world of reference materials and research.

Harjo-Moffer is something special, more than a keeper of records. She is a steward of traditional knowledge. She’s also frank, open, and dryly funny. She says that the first vision in her mind when she thinks of grave houses is her grandfather’s own, which she remembers from when she was a child. It was only a hundred yards or so from the front door of the allotment where she grew up, where anyone who pulled up in the drive would see it. “The family might not be on the property” anymore, she says, “but the grave houses still are. Some have fallen in and you can see the remains of the house and their personal items. The idea behind this is that even if the spirit wanders, they’ll always have somewhere to come home to.” They are not to be rebuilt, no matter how dilapidated. The tradition is to let them go back to the earth, along with the personal items placed within.

Those personal items offer another level of the grave houses’ intricacy and intimacy. Harjo-Moffer says that her father told her that the items should be carefully selected, something that the deceased loved or held close, to take with them on their journey.

Our conversation has a heaviness, not just from the subject matter, but from our shared identity as Native people. Looting of personal items from grave houses was once a large problem, so the locations of smaller cemeteries of the Muscogee (Creek) are closely guarded. In other places, they can be openly visited (and are protected), such as in Perryman Cemetery in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Harjo-Moffer shares that her family recently buried her nephew in a smaller family cemetery. Her brother, now the lead elder of their family, took the lead in building the grave house, and her grandsons assisted. They built the frame, loaded it into the truck, and then attached the roof and door later on. The process must be completed in four days or less, and the house is sturdy but simple. That’s not the case for all of them. Harjo-Moffer recalls seeing another so intricate it looked like a miniature mansion: “They must have been mighty special,” she laughs. Indigenous persistence must have room for both humor and sadness.

A slew of tribal members, officials, and historians—even those from my own community—were unwilling to speak about this topic. Protecting Native lines of thought is considered incredibly important, especially given the ways being Native was weaponized against communities in the past. There is always a fear that any information given will be taken, bastardized, burned down, or worse. I had to dig, and when that digging became quite difficult, I had to consider whether this knowledge is something that should be reported on, much less shared with the public. I found that it is—but only carefully.

I was asked not to share any locations, but I can describe one of these cemeteries, in rural Oklahoma. Eastern Oklahoma is nestled amongst the tree-filled foothills of the Ozarks, where there is an almost blue hue to the wind; a place of much sadness, but beauty, too. Among these trees and spaced-out family homes, one can find a small cemetery, not gated, with grave houses alongside “normal” graves. The path is dirt and rock, and there’s a bridge over the creek. It’s terrifying, for a split second, to think of all the grief concentrated in this one place, but it passes. The houses, though eerie, serve a purpose, one with murky origins, but important—particularly to the people who walked these paths, who died here, so far from what had been home.

I still wanted to know how these grave houses came to be, what caused a tradition of thousands of years to evolve into something new. I turned to a source from the Chickasaw Nation who was willing to help but unwilling to be named. Were there any Indigenous sources or citation systems that I had missed? My source shared stories from elders about the construction of grave houses and continuation of the tradition—but not their origin, only that it had been and shall be. Besides, even if they had that information, I am not a member of the Chickasaw Nation. They also shared their fears about this article, about the ways words could be twisted, and how Indigenous traditions are often characterized as primitive just because they do not fit into the white, Western model of logic and sourcing.

My last interview was with RaeLynn Butler, Manager of the Historical and Cultural Preservation Department of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and a member of the Raccoon Clan.

Butler is passionate about her work, but her tone is hushed, subdued when she talks about her, and the Nation’s, traditions. One of the primary missions of her department is to tend to rural family cemeteries that have been abandoned over the years, to “provide protection and preservation of these sacred places,” according to the Nation’s website. Today grave houses are usually placed either on the family property or in more populated public cemeteries, so these old, remote family cemeteries contain most of the historical examples of the practice. “The thing about spirit houses,” Butler says, “is they are a mix of modernity and the past. They exist on a spectrum between Christianity and our traditional religion.” They combine the practice of burying loved ones under the home with burying them in a designated graveyard.

The Muscogee (Creek) have maintained the tradition wherever they live, and some rules have stuck. Only men can build the house, and it must be completed within four days of death. Women can aid in painting and decorating the house, and the design is up to the family. But the tradition itself remains at risk, Butler says. As tribe members become more assimilated in American culture, they are less likely to want a grave house over their burial site. That worries her, she says, but there’s no real option except to press forward with preserving meaningful traditions. “That’s all we can do,” she says. “We have to talk about it, and share our stories, and not give in to silence.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook