Meet the Duo Molding the Weird, Wondrous Future of Jelly

From disturbingly realistic gelatin portraits to a jiggling Buckingham Palace, Bompas & Parr are pushing the wobbly envelope.

On the morning of May 18, 2012, Sam Bompas and his business partner Harry Parr were waist-deep in lime jelly. The two men wore red jumpsuits, all the better to stand out against more than 66,000 gallons of gelatin the color and consistency of the ectoplasm in Ghostbusters. Above them was the hulking, ironclad bow of the SS Great Britain, a Victorian transatlantic steamship that now serves as a museum piece. Normally, the ship stays moored in a glass display in the Great Western Dockyard in Bristol’s Floating Harbour. But for two surreal evenings, Parr and Bompas covered the surface in jelly, effectively encasing the vessel in a wiggling, illuminated sea which viewers were able to eat at the end.

At the time, it was the largest piece of jelly art ever attempted. But it’s not the pair’s wildest feat. Parr, who has a background in architecture, and Bompas, who worked in PR and real estate, have been friends since school. It wasn’t until 2007, however, that they joined forces and began to really push the gelatin envelope.

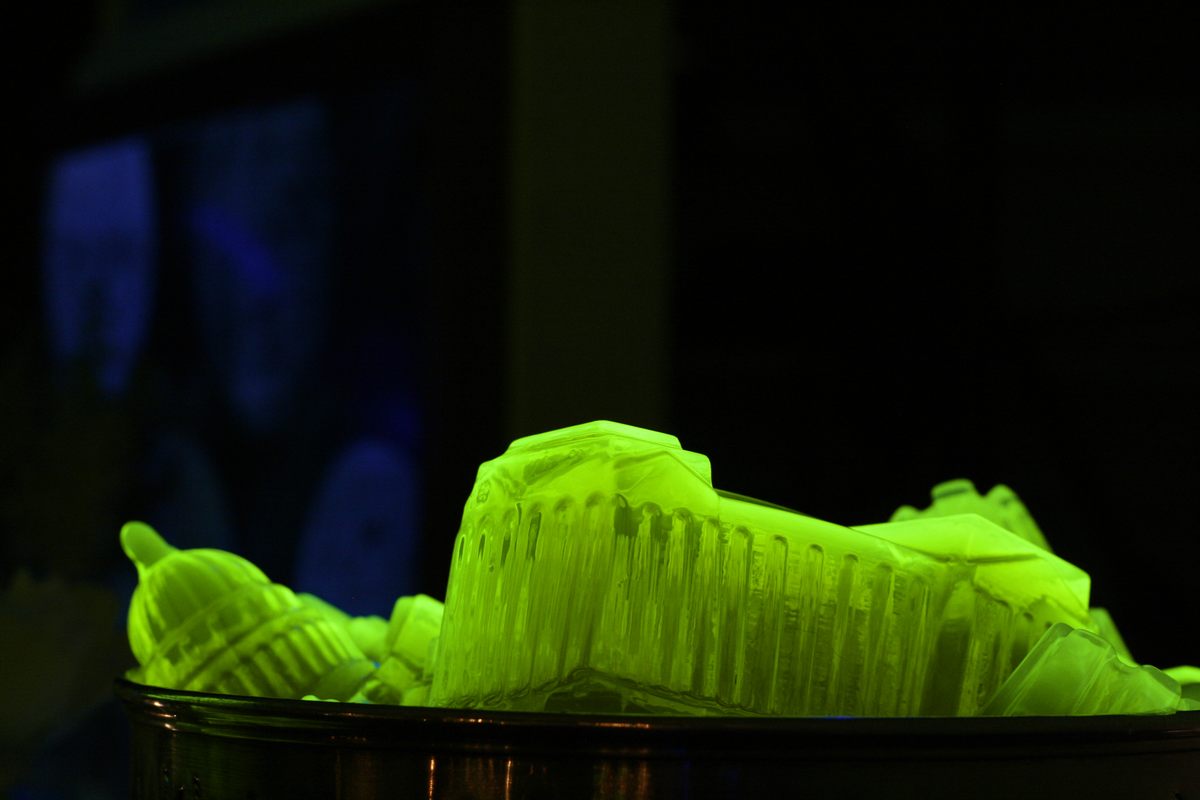

In 2007, they launched Bompas & Parr, a creative studio specializing in food art ranging from the mainstream to the avant-garde. Since then, they’ve made everything from a jelly replica of Buckingham Palace to a giant “flavor-changing” jelly that used sound and light effects to transform while participants consumed it. They’ve created gelatinous works in collaboration with architects including Norman Foster and chefs including Heston Blumenthal. Bompas has been banned from the tech festival Wired Live for attempting to explode jellies with IED devices— “It was probably for the best,” he says—and flirted with heresy by projecting a holographic Christ on the cross into jelly. “I thought people would be outraged, but no one actually was,” he says.

The brand periodically plays with the skin-crawling side of jelly, as in a recent workshop called Eat My Face, in which paying participants were invited to “explore the possibilities of anatomical jelly-making” with a trusted friend or partner. After breathing through straws while the alginate molds set along the contours of their cheekbones and jawline, each pair made and devoured hyper-realistic jelly busts of their partner’s face.

Bompas and Parr enjoy toying with the macabre and approach much of their work with tongue firmly planted in cheek. Yet while gelatin may not seem like a medium that lends itself to seriousness, the duo have earned a surprising level of cultural legitimacy over the course of their most unusual careers. CNN dubbed them “London’s sensory magicians” and the duo are both Fellows for the Royal Society of Arts, a rather lofty distinction that Bompas still regards with a certain incredulity.

“We’ve made jellies for weddings, for funerals, as art in art galleries,” Bompas says. The latter include a major display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and an entire production of elaborate jellies for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York as part of their exhibition on Versailles in 2018. “We had all the curators there with their hair standing on end as we were unmolding them with boiling water,” he says with a laugh.

The duo’s latest endeavor is to revitalize the heritage brand Benham & Froud, a London coppersmith founded in 1785 that once fashioned spectacularly baroque jelly molds for the British aristocracy. At the time, ornate wiggling turrets flavored with everything from exotic pomegranates to truffles were de rigueur among European courts, thanks to prominent chefs like Marie-Antoine Carême. Bompas & Parr hope to continue the tradition by offering state-of-the-art, detailed jelly molds for aspirational home cooks and chefs.

Elaborately shaped gelatin desserts have long entranced people. “Part of the reason it was a status symbol is the same reason that it is now a social media sensation: it acts as an optical lens, it catches the light,” Bompas says. After the American domestic sciences movement and Jell-O’s instant product turned jellies into a punchline in 20th-century gastronomy, Bompas and Parr are betting big that the medium is ready for a comeback.

“The pendulum all swings back, doesn’t it? Food now operates as fashion,” Bompas says. Recently, The New York Times asked why we’re so “obsessed with jiggling foods.” And while not every home cook is willing to attempt complex gelatinous feats, jelly artists range from the highbrow—Sharona Franklin, whose work landed in Vogue in 2020—to the intentionally bizarre, such as the work of Ken Albala, professor and the unofficial “Jiggle Daddy” of Facebook groups like “Aspics with Threatening Auras.”

Freddie Mason, the author of The Viscous: Slime, Stickiness, Fondling, Mixtures, who has, as he puts it, “a PhD in slime,” has a number of theories as to why jelly continues to find new cultural relevance. Much of it, he believes, ties into Susan Sontag’s theory of camp, which is that cultural phenomena are allowed to return to the cultural zeitgeist once they no longer pose a threat.

“Jelly did pose certain threats: it’s mechanization, it’s crap feminism, it’s hospital food,” Mason says. “Jelly is hospital food because it is good for times in our lives when the pleasures of mastication aren’t possible. When you can’t chew, when you’re dying, when you’re newborn, you get jelly.”

Jell-O is still a hospital staple, but now that gelatin is no longer synonymous with the rise of industrialized food, Mason believes we can go back to simply enjoying it for the deeply weird substance that it is.

“It tantalizes us. It confuses us,” he says. “[Jellies] exhibit some of the properties of life, but then they’re not. We can play with them and manipulate them in ways we cannot with living things.” Above all, he believes that gelatin’s animalistic origins and animated nature have much to do with why we’re so attracted to and repulsed by it. “Slime is a matter that seems to have some kind of will to it,” he says.“It grabs you and holds onto you in the way that we do with the world. In the wobble and the shudder of jelly, we see ourselves.”

For his part, Bompas is perfectly happy to lean into his medium’s Uncanny Valley allure. “Jelly that is made of gelatin is of the flesh,” Bompas says. It’s a visceral truth that’s easy to forget when looking at a brilliantly hued set of molded jellies. Although Bompas & Parr have experimented with vegan alternatives, there’s nothing that replicates the original, which comes from the rather gruesome process of washing an animal carcass in acid.

Part of what appealed to Bompas about the original Benham & Froud was its flair for optical illusions. The company’s designers, early on, cleverly found a way to insert multiple layers of color into a pudding. “Unless you knew the secret, it wasn’t obvious how it was done,” Bompas says.

Today’s jelly artists accomplish similar visual trickery with knife-tipped syringes. In Bompas & Parr’s case, they’re increasingly working with copper electroforming, a process of attracting copper molecules using a low voltage charge that produces absurdly intricate molds. Much like how jelly artists of old used clever sleights of hand to delight French monarchs, Bompas and Parr are using tech to take gelatin to wobbly new heights.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook