The Bizarre, True Story of Gef the Talking Mongoose

Oh, and Gef was a ghost too.

Sometime around 1933, two teenage cousins, Harry Hall and Will Cubbon, paid a visit to a new friend of theirs named Gef. Gef lived in a remote, windswept farmhouse on the Isle of Man. He was very shy, and the cousins could hear and talk to him, but never saw their new friend. From behind a wall, Gef would guess heads-or-tails when a coin was flipped or play catch with a rubber ball through a hole in the attic ceiling.

But soon, Gef began misbehaving: spitting and threatening the boys that he would “wet on [their] head!” Gef, it turns out, was no normal boy—he was a poltergeist in the form of a talking mongoose.

Doarlish Cashen, the farmhouse where Gef resided, was in many ways the stereotypical haunted house. It was an ancient farmstead on a notoriously fairy-filled, desolate isle, situated some 725 feet above sea level in the cold, gray waters between England and Ireland.

In 1917, married couple James and Margaret Irving moved into Doarlish Cashen, where they were soon joined by baby daughter Voirrey. After several years of peace, Gef suddenly appeared.

One fateful evening in September 1931, following an outbreak of strange tapping sounds, a creature let out a series of growls from the upstairs attic. The Irving family went to investigate. The growls soon turned to “gurgling sounds,” as James Irving would later recall in a 1937 interview, like those of a baby learning to talk.

Fascinated, Irving taught the creature English, saying words out loud for Gef to repeat parrot-fashion. Gef was grateful. In a letter Irving wrote in 1934, Irving recounted Gef saying, “For years, I could understand all that was said. I tried to talk, but couldn’t, until you taught me.”

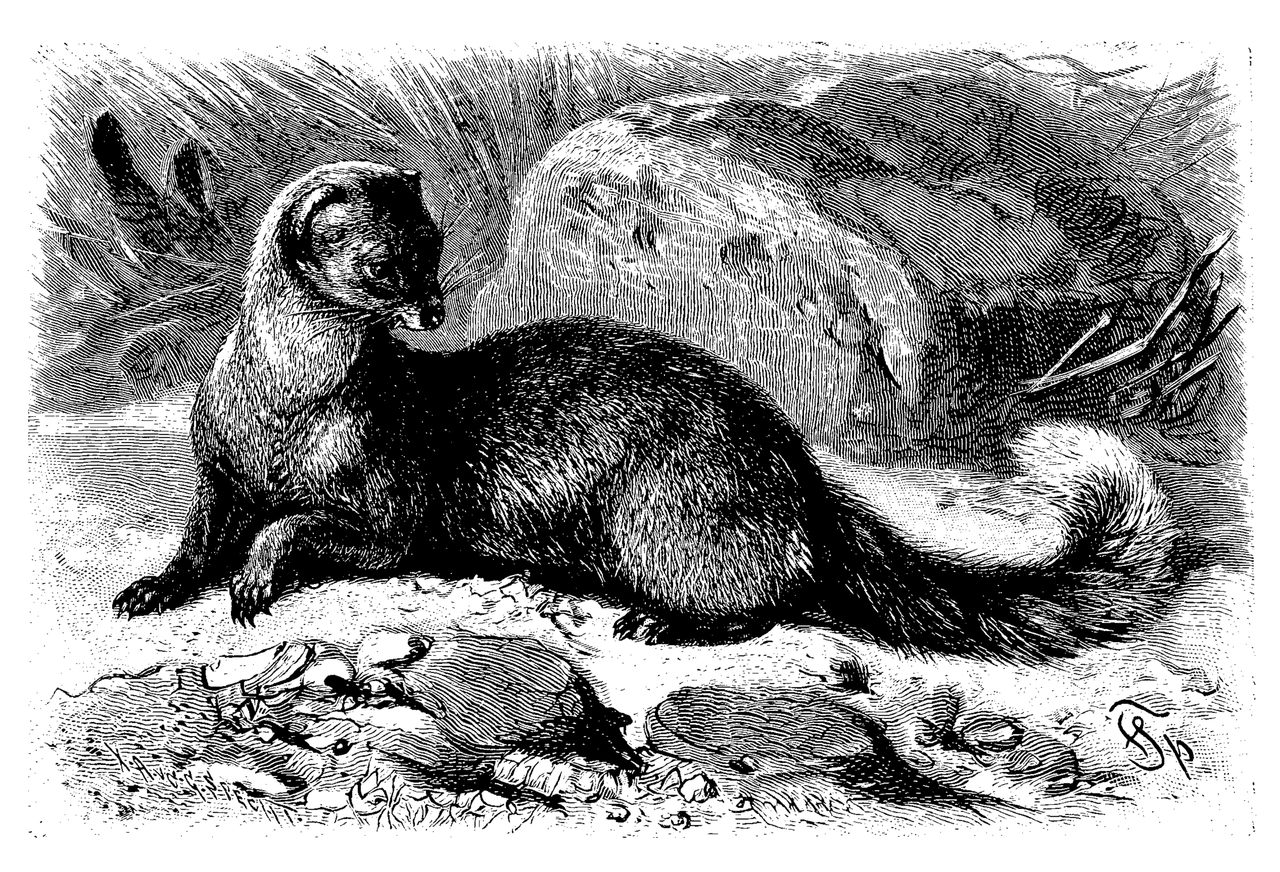

With his newfound language skills, Gef told Irving he was a ghost of a mongoose. He had been born in Delhi, India, on Monday, June 7, 1852. “And I shall haunt you with weird noises and clanking chains,” Irving recalled Gef declaring in the same 1937 interview.

In his book Gef! The Strange Tale of an Extra-Special Talking Mongoose, librarian Christopher Josiffe compares Gef to a Victorian music hall comedian. Gef’s fondness for playing pranks and making, what Josiffe calls, “outspoken and irreverent comments,” are a central part of Gef’s “enduring appeal.”

The Talking Mongoose “repeatedly lampooned [the Irvings], comparing [James Irving] to a Dickens character or saying his head resembled an onion,” says Josiffe.

But Gef also had a mean streak, says Josiffe. When Gef once spied Margaret “disrobing before bed, he called out the name of each item of clothing or underclothing as she removed them.”

All this was odd enough, but things got even stranger when, in February 1937, Hungarian-born psychoanalyst Nandor Fodor turned up on the Isle of Man to investigate. Fodor repeatedly interviewed the Irvings, particularly James Irving, compiling a thorough account of Gef the Talking Mongoose in his 1951 book, Haunted People: Story of the Poltergeist Down the Centuries.

English barrister and author Alan Murdie is an expert on poltergeists, having just recently contributed a chapter on the subject to the new anthology, Deep Weird. Murdie is also the current chair of England’s Ghost Club, an age-old body devoted to the study of spooks, of which Fodor himself was once a member. Having studied the club’s archival records, Murdie says that Fodor had some creative, Freudian-influenced ideas around the origins of poltergeists—ideas that eventually led him to Gef.

Fodor ditched the theory that poltergeists were invisible spirits of the dead, and instead suggested they were the psychic manifestations of a person’s subconscious. He believed living people could conjure real hauntings with only their thoughts. These psychic hauntings were powerful enough to throw objects or levitate tables. “What Fodor did was focus attention on the unconscious mind,” explains Murdie, instead of apparitions of the dead.

At the time, Fodor’s ideas were very controversial. His specific idea that there was a Freudian link between sex and spooks was “not a popular one,” says Murdie.

Some scholars, such as English historian Kate Summerscale, argue that Fodor needed a new case to back up his fringe theories—and that’s where Gef comes in.

Stories about Gef the Talking Mongoose had already been widely published in British newspapers, making the ghostly mammal a perfect subject for Fodor to investigate. Fodor arranged to lodge in the Irvings’ farmhouse for a week, hoping to interview Gef personally.

During his time on the Isle of Man, Fodor investigated the scenes of Gef’s antics, diligently interviewed witnesses, and tried his best to communicate with the beast himself. But Gef wasn’t having it, and the psychoanalyst never got to meet the talking mongoose.

In the end, the psychoanalyst wrote the mongoose a goodbye letter. (Gef could read too.) I am “very disappointed you did not speak to me,” he wrote. Nonetheless, “I believe you to be a very good and generous mongoose” and “I brought you chocolate and biscuits.”

Ultimately, Fodor concluded that Gef had been projected from the bored mind of James Irving, an intelligent and educated man, who had formerly enjoyed a more lively life on the British mainland. When Irving died, stories of Gef also faded.

Fodor’s bizarre investigation has now been adapted into a new film, Nandor Fodor and the Talking Mongoose, starring British actor and comedian Simon Pegg as Fodor and author Neil Gaiman as the voice of Gef. Unlike many films inspired by ghost stories, Nandor Fodor and the Talking Mongoose is billed largely as a comedy.

Josiffe, for one, appreciates the film’s comedic tone, as “absurdity and surreal craziness already surround the ‘facts’ of the case.”

For Murdie, the film’s humorous approach “is really only to be expected.” Laughter is often a common reaction to horror. It’s “a defense mechanism,” says Murdie, “since the paranormal and its implications make many people feel deeply uncomfortable.”

Josiffe imagines Gef would also approve of the film: “Any cultural product or entertainment that helps spread Gef’s fame further is likely to meet with his approval.”

Despite all the bizarre stories surrounding Gef, no concrete evidence has ever been uncovered about the mongoose’s origins or source. Were the Irvings suffering from a communal delusion? Was Gef a manifestation of James Irving’s unconscious mind? Was it all made up? Josiffe and others don’t know, and that’s part of the fun.

Josiffe feels that “the lack of resolution adds to the case’s appeal,” and he hopes it stays that way. “When I was writing my book, I was terrified I might unearth Voirrey’s secret diary in which she confessed to having faked the whole thing.” Thankfully he didn’t, so the mystery of Gef the Talking Mongoose continues—now on the big screen.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook