Freemasons of the Caribbean

photograph by Darmon Richter

Freemasonry arrived in the Caribbean in the 18th century. It came by water, carried on the ships that sailed from Spain, England, the Netherlands, and France. Military men established many of the first lodges, although the practice was subsequently spread and maintained by colonial governments, merchants, and traveling businessmen.

In the mid-to-late 18th century, the “Craft” would see alternating periods of rapid growth, and stagnation. Lodges opened and closed in quick succession as the European powers battled both amongst their Caribbean colonies, as well as back at home. The French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and others would all have an impact on the practice of freemasonry in the Caribbean.

Masonic graves in the Cristóbal Colón Cemetery, Havana, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Masonic graves in the Cristóbal Colón Cemetery, Havana, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The earliest record of an English-speaking lodge in the Caribbean is Antigua’s Parham Lodge No. 154 — consecrated in 1738. It was around the same time that other pioneer lodges began springing up in St. Kitts (St. Christopher’s Lodge No. 174) and Jamaica (Great Lodge of St. John No. 192, and Port Royal Lodge No. 193).

Meanwhile, provincial grand lodges were appeared soon after both in Barbados (1740) and Bermuda (1745). In 1788, Irish Freemasonry would follow the English and Scottish rites, to establish the Union Lodge No. 690 in Trinidad and Tobago, as well as a significant presence in both Jamaica and Bermuda.

It’s interesting to note that in the Spanish colonies, however, freemasonry took much longer to establish itself.

A masonic lodge in the backstreets of the Dominican Capital (photograph by Darmon Richter)

“Esperanza” Lodge No. 9, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The influence of the Roman Catholic Church was largely the cause for this, due to the anti-masonic position taken by the Vatican ever since the papal ban in 1738. Trinidad and Tobago wouldn’t embrace freemasonry openly then, until the islands passed from Spanish to British rule in 1797. In the Spanish (and later, Haitian) controlled Dominican Republic, freemasonry was not permitted to spread until after the 1844 Dominican War of Independence. The Grand Lodge of the Dominican Republic was founded shortly after, in 1858. In Cuba, likewise, freemasonry would not begin to flourish until 1898, when the island’s battle for independence would earn sympathy from the US, and escalate into the brief-yet-bloody Spanish-American War.

In the French and Dutch colonies, a similarly religious climate would slow the early progress of the Craft — Lodge “Les Freres Unis” would eventually be warranted by the Grand Lodge of France, in St. Lucia, 1795. As colonial grip loosened however, religious doctrine would relax and the societies took more of a hold, with new lodges popping up in Guyana, in the Dutch colony of Demerara, in Trinidad and Tobago, and in Martinique, so that the early 19th century was characterized by rapid acceleration of freemasonry’s popularity in the Caribbean.

In Haiti, too, the Craft arrived by way of the Grand Lodge of France. In 1697, the Spanish had ceded the Western portion of Hispaniola to the French, and by the 18th century, the colony (then known as “Saint-Domingue”) enjoyed a booming trade in coffee, sugar, and cocoa. With the increased movement of merchants, colonial officers, and slavers, the ideas and practice of freemasonry also became well established. When Haiti won its independence, and utterly abolished slavery at the end of the 1791-1804 Haitian Revolution, masonry was so ingrained into local culture that the all-black revolutionary government inherited the Craft amongst their other spoils of war.

Masonic tombs in the Grand Cimetière de Port-au-Prince, Haiti (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Masonic tombs in the Grand Cimetière de Port-au-Prince, Haiti (photograph by Darmon Richter)

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, the former slave who led the revolutionary forces against the French, is himself reputed to have been a devout freemason. His own signature seems to attest to the fact, with its combination of two lines and three dots that mimic a popular masonic shorthand symbol of the time. In fact, some sources claim that masonry was so integral to Haitian culture and leadership, than any president of the country who was not a mason prior to office was ordained on the occasion of their election.

Meanwhile another of Haiti’s founding fathers, Jean-Jacques Dessalines — the self-styled “Emperor Jacques I of Haiti” — was similarly invested in the Craft. The National Museum of History, in the center of Port-au-Prince, houses artifacts such as the slave-turned-emperor’s own sword and scabbard, clearly engraved with square and compass motifs.

Haiti’s National Museum of History is a repository of masonic artifacts (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Masonic symbolism mixes with vodou motifs, in a Port-au-Prince sculpture museum (photograph by Darmon Richter)

It was another Haitian freemason, in fact, who established freemasonry in Cuba.

Masonic ideas had begun to spread around Cuba from 1763 onwards. Perceived as anti-religious by the Spanish authorities, however, it had been largely outlawed. Later, during the island’s brief occupation by Britain, the activities of English and Irish military lodges lay the foundations for the development of a Cuban charter.

When the Haitian Revolution kicked off in 1791, thousands of French colonists fled the uprising, escaping a widespread massacre of white slavers to land at ports such as Trinidad in the south of Cuba. Joseph Cerneau was one such French-Haitian freemason. He founded Cuba’s first lodge in 1804, the Cuban Theological Virtue Temple in Havana.

Cuban freemasonry is noteworthy for being one of the most overt and colorful rites in the Caribbean. Rather than the secrecy that so often surrounds masonry in other parts of the world, Cuban lodges take pride of place in town centers, decorated in bright colors and with all the subtlety of an orchid in bloom. They permit female membership, and “brethren” favor relaxed attire over the traditional suits and ties, not only on account of the heat, but also so that no member should feel embarrassed for not owning formal clothes. More interesting still is that Cuba is the only country in the world where freemasonry has been protected by a communist regime.

“Logia Aurora del Bien” No. 10551, in Trinidad, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

“Logia José Jacinto Milanés” No. 21, in Matanzas, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

It is well known that freemasonry was heavily suppressed by the Soviet Union; Stalin was not a man who liked having secrets kept from him. Yet in a post-revolutionary Cuba, ruled over by the Cuban Communist Party and closely allied to the USSR, it was elevated to a highly respected position within society.

Much of this stems from the Cuban War of Independence, and the subsequent American-Spanish War. Freemasons were hugely influential in the formation of the United States, and as Cuba battled for freedom from the Spanish they won the support of many lodges in the US. Besides, Cuba’s own revolutionary thinkers — social philosophers such as José Martí and Carlos Manuel de Céspedes — were themselves outspoken freemasons.

The José Martí Memorial in Havana, Cuba, during the May Workers’ Day parade (photograph by Darmon Richter)

In aligning itself with Cuba’s proud revolutionary past, Fidel Castro and his 1965 “Communist Party of Cuba” had no choice but to embrace those bold thinkers who came before. To denounce freemasonry would have been to deny Cuba its national heroes — a poor choice for any political movement with hopes of stable government.

There is, however, a popular theory that closer ties the Castro brothers to the Craft. In 1956, 82 freedom fighters set sail from Mexico to Cuba, aboard a yacht named Granma. Amongst them was Che Guevara, along with both Fidel and Raúl Castro. As these revolutionaries began their assault on the despotic government of President Fulgencio Batista, the story goes that a masonic lodge offered them shelter, hiding them from Batista’s troops, a gesture of support for their revolutionary mission. It might certainly explain Fidel Castro’s subsequent tolerance for the craft; with some versions of the story going further to suggest that Castro himself was raised to the level of master mason prior to his appointment as President of Cuba.

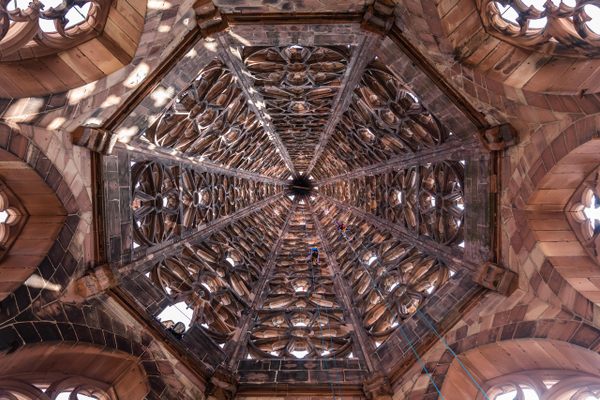

“Gran Logia de Cuba,” in Havana (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Above the masonic crest, the 12 clock points are marked with zodiac signs (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A square & compass adorn the globe on top of Cuba’s Grand Lodge (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Today there are almost 30,000 practicing freemasons in Cuba, spread across 316 provincial lodges, and all answering to the “Gran Logia de Cuba” in Havana. The “Grand Orient” Lodge in Haiti claims 48 provincial lodges and around 6,000 practising masons. The Dominican Republic has 1,200 masons. In the English-speaking Caribbean nations, meanwhile, the Craft continues to move from strength to strength, with 45 lodges in Jamaica, 23 in Barbados, 21 in Guyana, 20 in Trinidad and Tobago, 14 in Bahamas and Turks, and another 14 in Bermuda. (Numbers are from this report and cited on Wikipedia).

Not only has freemasonry contributed to the development of the Caribbean nations — their passage from colonies to autonomous states — but it continues to play an integral role in Caribbean culture today. The resultant rites are as unique, as varied, and as colorful as those nations are themselves.

Masonic graves in the Cristóbal Colón Cemetery, Havana, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Masonic graves in the Cristóbal Colón Cemetery, Havana, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Masonic graves in the Cristóbal Colón Cemetery, Havana, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Masonic graves in the Cristóbal Colón Cemetery, Havana, Cuba (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Darmon Richter is a freelance writer, photographer, and urban explorer. You can follow his adventures at The Bohemian Blog, or for regular updates, follow The Bohemian Blog on Facebook.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook