How Intrepid Biologists Brought Natural Balance Back to the Aleutian Islands

To save birds such as the cackling goose, first the foxes had to go.

Steve Ebbert was at least a mile off Little Sitkin Island in the Bering Sea when the boat’s engine failed. Faced with the impossible task of paddling a 750-pound inflatable loaded with engines and gear in 15-knot winds, he grabbed the anchor and hurled it shoreward, aiming for a giant kelp bed. Usually he would have fought like hell to avoid propeller-clogging kelp, but in this case he was praying the anchor would get stuck in it so he could pull the boat toward shore. Luckily, the anchor snagged. He tugged the boat to that point, then frantically hoisted the anchor and chucked it again. And again. And again. Finally, he reached the beach. “In the Aleutians, if your outboard stops and you’re offshore and the wind is blowing, your next stop could be Australia or the Arctic ice cap,” Ebbert says, remembering how happy he was to reach land. “It’s not a good feeling when you pull that cord and the engine doesn’t start.”

That was one of Ebbert’s early near-disasters after he arrived at the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in spring 1995 as a young, sharpshooting biologist on a grisly, seemingly impossible mission: to kill every last fox on more than 40 islands. He would be carrying on a decades-long endeavor to restore some kind of natural balance to this otherworldly archipelago marred by more than 200 years of human meddling. Ebbert and a cadre of intrepid biologists braved high seas, gale-force winds, and even erupting volcanoes at the edge of the world to write one of the greatest conservation success stories in U.S. history.

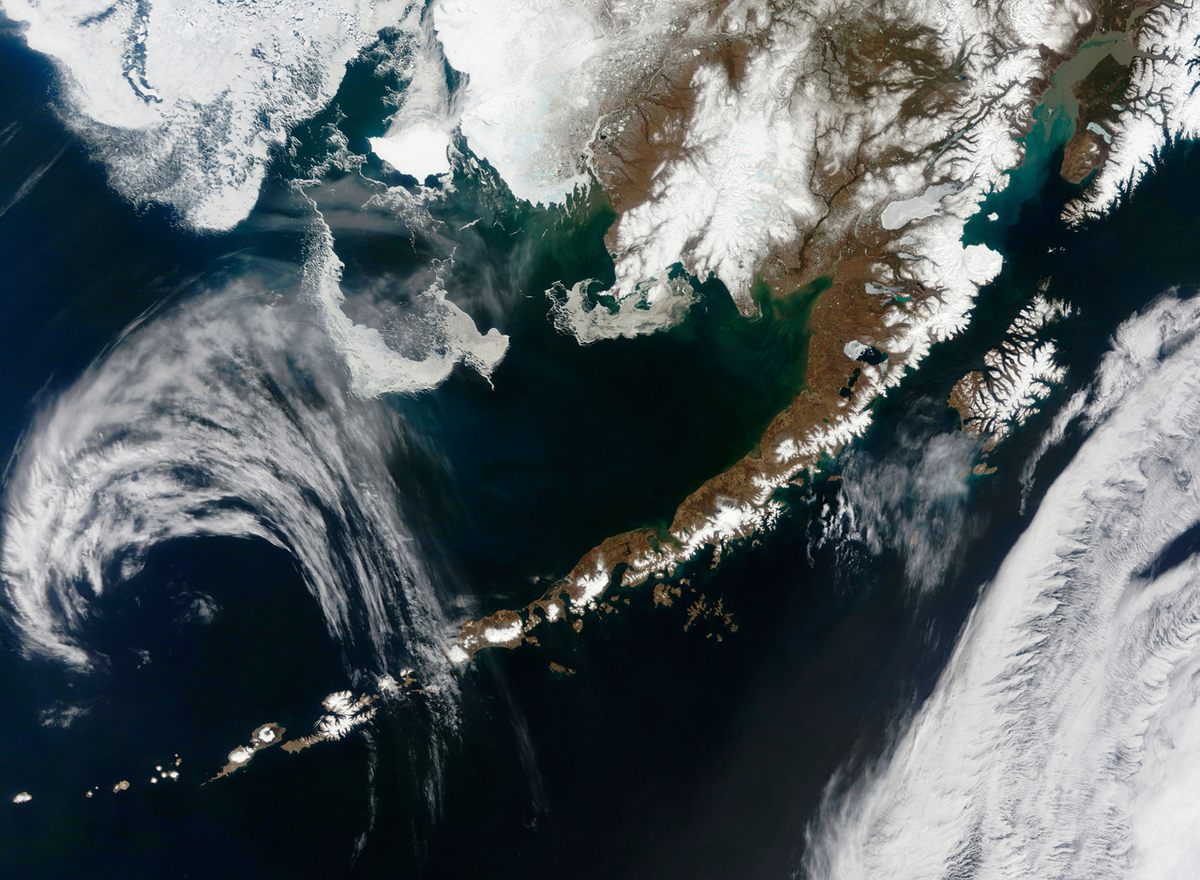

The Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge is a rugged landscape comprised of 3.4 million acres across 2,500 volcanic islands—so remote most people have never heard of them—arcing from the end of the Alaskan Peninsula to just short of Kamchatka in the Russian Far East. Treeless tundra, snow-covered peaks, rocky coastlines, black sand beaches, muskeg ponds, kelp beds, and coral reefs there provide literal refuge to a profusion of life, including 450 types of fish, 26 species of marine mammal, and 40 million individual birds, from 30 species—including 80 percent of North America’s nesting seabirds.

The Aleutians at the heart of the refuge were a particularly blissful place for a bird to raise a family until Russian fur trappers arrived in the mid-1700s. “They came to hunt the sea otters and fur seals, but they saw an opportunity to put foxes on the islands,” says Ebbert. “There was a ready supply of food: birds, eggs, and chicks. As a result, almost every island where you could land a boat was stocked with foxes that would reproduce.”

Within a few years of releasing a couple pairs of foxes on a given island, the trappers could return to collect pelts—red, silver, white, the coveted “blue” (actually blackish)—by the shipload. As the canines flourished, the raucous sound of millions of birds jostling on the shores and cliffs hushed. By 1811, birds were becoming so scarce that native Aleuts living on Attu, the site of the first known fox introduction, at the distant western end of the chain, could no longer make traditional clothing from bird feathers and skins. They turned to fish scales. Meanwhile, fine ladies in the United States and Europe were draping themselves in luxury coats and stoles made from island-grown foxes, and pairing them with ornate feathered hats of such outrageous proportions that some women had to kneel to climb inside their carriages.

“That continued until the stock market crashed,” Ebbert says. “Fur fell out of favor. People didn’t want to trap anymore. When World War II came, many of the Aleutian Islands evacuated, most people never returned. And then the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service finally wised up—realizing you can’t have a wildlife refuge if you’re farming foxes.”

By 1940, when fox harvesting officially ended and the Aleutian Islands became part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, some feared it was already too late for birds such as the Aleutian cackling goose. It was widely thought that the migratory birds were already extinct, but a World War II veteran named Bob Jones, who in 1947 became the first manager of the refuge, saw hope in faint skeins of geese winging west. Confident the geese that he saw weren’t the common Canada variety, he launched an epic goose chase to find a remnant breeding population, which he thought must be hiding somewhere among islands so remote they were never stocked with foxes.

Navigating crashing waves, fierce winds, and blinding fog, Jones sailed the isles in a shallow, 20-foot dory, occasionally hitching rides on larger vessels to reach the most distant islands. He searched in vain for 15 years, but refused to give up. Then, in 1962, he traveled aboard the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Winoa to reach Buldir Island in the far west of the Aleutians. There, he looked up in the sky and saw 56 Aleutian cackling geese, “flying off the high steep cliffs,” he wrote in his field notes that day. At last, he’d found a surviving flock. It contained about 300 birds, and he eventually found two additional populations on similarly remote isles. “It turned out the foxes had eliminated all the geese except for on those three islands,” Ebbert says. “The solution for bringing back the goose was clear—kill the foxes.”

Upon the signing of the 1966 Endangered Species Preservation Act (the precursor to the Endangered Species Act), the Aleutian cackling goose was among the first 80 animals on the Endangered Species List. Jones continued his campaign to systematically exterminate the foxes. In the early days, he used mostly poisoned baits, but when they were banned in the 1970s, he started looking for biologists who were also good marksmen and trappers. As he gained notoriety for his efforts to save Aleutian wildlife, including sea otters and many other species, he became known as “Sea Otter” Jones. In his 33-year tenure as refuge manager he overcame many unique challenges, not least of which was how to manage caged wild geese as they coped with seasickness.

Jones learned that lesson while helping to round up geese for a captive-breeding and reintroduction program. Some of those captive-raised animals started breeding on the islands in 1984. By the time the Aleutian cackling goose was removed from the Endangered Species List in 2001, the population had grown to 37,000.

Steve Ebbert was hired in 1995 to continue the efforts to eradicate foxes that began with Jones. Ebbert had grown up on a farm in Indiana, trapping raccoons and muskrats. Trained in forestry and wildlife biology, he had experience with computer mapping, remote sensing, and predator (coyote) control. As much as it was his dream job, he was a dream candidate for leading the efforts to exterminate the refuge’s foxes.

Ebbert stationed field crews throughout the islands most summers and routinely helped run the trap lines himself. He loved the work, but it’s not for everyone, he admits. “The ship drops you off in May and comes back in early September. You’re on your own, and you have to do without. If you have a problem with your roommate, you can’t walk away. You have to figure it out. It’s like being on a spacecraft.”

Each crew of between two and 10 was furnished with everything they needed to make shelter, a kerosene heater, and enough food in a cardboard box to hopefully last until the ship returned at the end of summer. Drinking water was in the creek; bathrooms were on the beaches (flushed twice daily at high tide). Free time was often spent trading novels and playing checkers. The rest of the time was spent setting and checking traps.

Before departing for the Aleutians, the crews received special training—not just for trapping, but to prepare for the gale-force winds that could flatten their tents and steal their boats. “The tents are built on plywood floors with canvas over steel pipe frames staked to the ground with cables,” Ebbert says. “But a storm can rip your tent and bend the poles. It’s better to collapse your gear, put heavy rocks on it, and find cover.”

Keeping a boat safe and operational under those conditions was particularly tricky and risky. They could tear and deflate, run out of gas, wash away, break down. Every boat had two engines in case one fails—though in rare cases, they both did, as Ebbert learned early on.

As if blustering winds, fierce seas, and extreme isolation aren’t enough, certain Aleutian Islands sometimes hurtle boulders and lava. In August 2008, a group of seabird biologists living on Kasatochi Island out in the middle of the chain had to be rescued when the Alaska Volcano Observatory reported an earthquake that lasted for 20 minutes. The island’s long dormant volcano was about to blow. “Our ship was far out in the chain,” Ebbert remembers. “It would take days to get to them.” Fortunately there was a spare boat, aptly named Homeward Bound, nearby in Adak. Through 30-knot winds and high seas, the boat reached the island and the biologists scrambled aboard, taking with them only what they could carry. They were heading west, engine roaring, when the volcano erupted, carpeting the entire island with ash and lava.

Island life was, in some ways, like living in a giant museum. Trappers searching foxholes found Native American artifacts and caves where ancient Aleuts had buried their dead. Relics from World War II——shipwrecks, downed planes, twisted metal, and even ammunition—littered the beaches. In 1998, Ebbert was helping set up a trapper cabin on Attu Island when he came across at least a dozen sticks of dynamite in a crate buried in the sand. Another time, he discovered a stack of Japanese hand grenades. In 1999, a field crew stumbled across an unexploded naval mine that had washed ashore and settled in a creek channel. “Round with metal spikes, the mine looked like it came out of a cartoon,” Ebbert says. “Experts from Fort Richardson/Elmendorf base flew out and blew it up.”

Despite so many near catastrophes, the fox-eradication program was an incredible success. As of 2017, more than 40 islands—1.4 million acres in total—were scrubbed fox-free. “All the ‘gettable’ islands had been gotten,” Ebbert says, so they turned more attention to removing other invasive mammals—rats, livestock, rabbits, marmots—that can make life difficult for nesting seabirds.

Rats, for example, are notorious interlopers on many of the world’s islands—remote and otherwise. Known for their ability to thrive just about everywhere, from sewers to penthouses, rats found the big chunks of volcanic rock out in the middle of the ocean a chain of utopias overflowing with abundant birds for food. The first rats to invade the Aleutians likely arrived as stowaways in the 1780s on a Japanese fishing vessel that sunk in the western part of the chain. From that time on, many islands in the chain have been infested from “rat spills,” or by rodents that swam or drifted to new territory. If the foxes weren’t bad enough for them, the evolutionarily defenseless seabirds were decimated by rats scurrying into their nesting borrows.

The problem got so bad that in the early 1990s, refuge managers developed a rat-spill program, similar to oil-spill response teams, to provide emergency responders equipped to speedily target and contain new invasions.

In 2008, biologists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the non-profit Island Conservation and Nature Conservancy boldly launched a controversial poison campaign on an island so heavily infested it had had been renamed Rat Island. Helicopters broadcasted poisonous payloads—small cakes laced with rodenticide thought to be safe for the native birdlife.

Indeed, the project got rid of all the rats and in time, many of the nesting birds returned. However, it had an unintended consequence of killing dozens of bald eagles and hundreds of glaucous-winged gulls. Biologists theorized that the gulls ate the poison, and the eagles ate the gulls. So plans to poison rats on any other islands were abandoned.

Unlike the rats, which arrived by (predictable) accident, every other type of nonnative mammal found on the Aleutians was put there deliberately. “People think of these islands as remote and seldom visited, but they didn’t escape this instinct of humans to place animals on islands where they don’t belong,” Ebbert says. Hoofed animals—from cattle, sheep, and hogs to caribou and horses—have altered the native plant communities, caused erosion, and trampled shorebird nests. Removing livestock, however, is a hot-button issue, especially on a small number of refuge islands that contain privately owned land. Cattle and caribou have been eliminated on only a few islands, but none recently.

In his last years working on the refuge, Ebbert and his crews focused heavily on European rabbits. “In a lot of ways, the rabbits were the hardest,” Ebbert says. “They can get to places where we can’t. They’re small enough that they can have burrows on the side of a cliff and never come within rifle range. Probably to avoid eagles, some don’t even come out in daylight.” They also breed like, well, rabbits—often faster than even the most sharpshooting biologists could target them. They succeeded in exterminating bunnies on Poa Island, one of five islands with rabbits, and that took dangling from cliffs and crawling in the darkness, using infrared night vision and silenced rifles with ballistic scopes.

In 2017, Ebbert took stock of the invasive species removal program. All of the fox eradications that were practical to complete were complete. Politicians had no appetite for further efforts to eradicate cattle and caribou. The rat-spill prevention and shipwreck response was shifting out of the refuge staff’s responsibilities. Ebbert figured he’d made his mark. He was 58 and wanted to retire so he could visit family back in Indiana and travel the country in his camper trailer.

After Ebbert put down his rifle and hung up his life vest, on Halloween of that year, the refuge did not fill his position, amid nationwide staff cuts in national wildlife refuges. There are no current eradication plans, and none planned for the near future, just some remaining efforts to prevent more invasions and respond to them should an intruder turn up.

“There will always be threats of new invasions,” Ebbert says. But the lack of foxes will stand as his legacy. With the islands’ remote location and protected status, it’s unlikely they will get reintroduced. “Many years from now, each trapper that participated in the eradication effort can point to an island on an Alaska map and say, ‘I know I made an enduring difference there that summer, and the island and seabirds that nest there are better for it.’” By the end of those summers, he says, “our beards were longer, we were leaner, and we were stronger. But we turned back the clock—this was very rewarding.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook