Found: Remains of a Half-Neanderthal, Half-Denisovan Ancient Human

We finally have first-generation evidence that our ancestors interbred.

In 2008, scientists found a finger bone fragment in a cave that changed our understanding of human ancestry. The bone’s mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) did not match up to the genetic material of Neanderthals or other early humans. It belonged to what we now call Denisovans, a recently defined subspecies of archaic humans named for Siberia’s Denisova Cave. Though they separated from the Neanderthals more than 390,000 years ago, we know that the groups periodically interbred. For the first time, however, scientists have identified remains of an individual with one parent from each group. They published their findings today in the journal Nature.

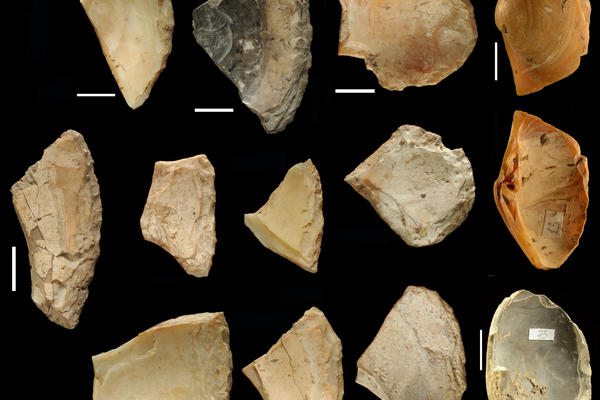

The finding comes by way of another fateful fragment, found in Denisova Cave in 2012 by Russian archaeologists. Years passed before the bone underwent any kind of testing, eventually arriving in 2015 at the University of Oxford for collagen fingerprinting which established that the bone had belonged to a hominin, a group of bipeds that includes modern humans and our immediate ancestors.

In 2016, the fragment fell under the auspices of Viviane Slon at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, who pulled from it some highly unexpected results: 38.6 percent of the DNA fragments corresponded with the Neanderthal genome, while 42.3 percent lined up with the Denisovan genome. This roughly even split was “too good,” said Bence Viola, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toronto and an author on the study. “You think that somebody screwed up something in the lab.” Nope—Slon repeated the tests after drilling a new sample from the bone, and confirmed her original results.

This first-time first-generation evidence, however, is not the only reason for anthropologists to get excited about this finding. This individual’s Neanderthal mother, the researchers found, had more in common genetically with Neanderthals living in western Europe than with an older Neanderthal who had lived in Denisova Cave, providing new insights into Neanderthal migration.

The team was able to establish the sex of each parent thanks to the specimen’s mDNA, which can only be inherited from the mother and was, in this case, Neanderthal-like. The chromosomal makeup revealed the individual to have been female, and the thickness of her bone fragment suggests that she lived to be at least 13 years old.

We’ve got a long way to go on our Denisovan details. Because we only have part of a finger and a handful of teeth, we don’t even know what they looked like. But if they’re anything like their Neanderthal counterparts, they were actually probably pretty smart.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook