How an Indigenous Chef Fights for Food Sovereignty

Johl Whiteduck Ringuette wants to give indigenous Canadians control over their own food.

Johl Whiteduck Ringuette’s life changed when he took part in a Shake Tent ceremony in the early 2000s. An indigenous rite in which participants attempt to make contact with spirits for guidance and healing, the ceremony was a way to recover something he felt had been stripped from him: his Anishinaabe identity. This set him on a ferociously ambitious path to not only establish an indigenous restaurant and catering business in Toronto, but to stake a claim for indigenous food sovereignty in Canada.

Born in a rural area in northeastern Ontario, he learned from his parents and older siblings how to snare rabbits and partridges, ice-fish, and cook over an open fire. This established his early love of food and cooking. Still, though his father was part Mohawk and his mother from the local Nipissing peoples, he was not familiar with rites and ceremonies traditionally associated with everyday indigenous life.

After high school, Ringuette, now 52, moved to Toronto and worked at a series of catering and food-service jobs to get by. By the 2000s, he had switched to community service, working at, among other organizations, Aboriginal Legal Services, which helps indigenous people navigate the legal system. Through this work, he saw firsthand how indigenous people were sometimes locked up for loitering because, he says, they were simply “sitting on a bench.”

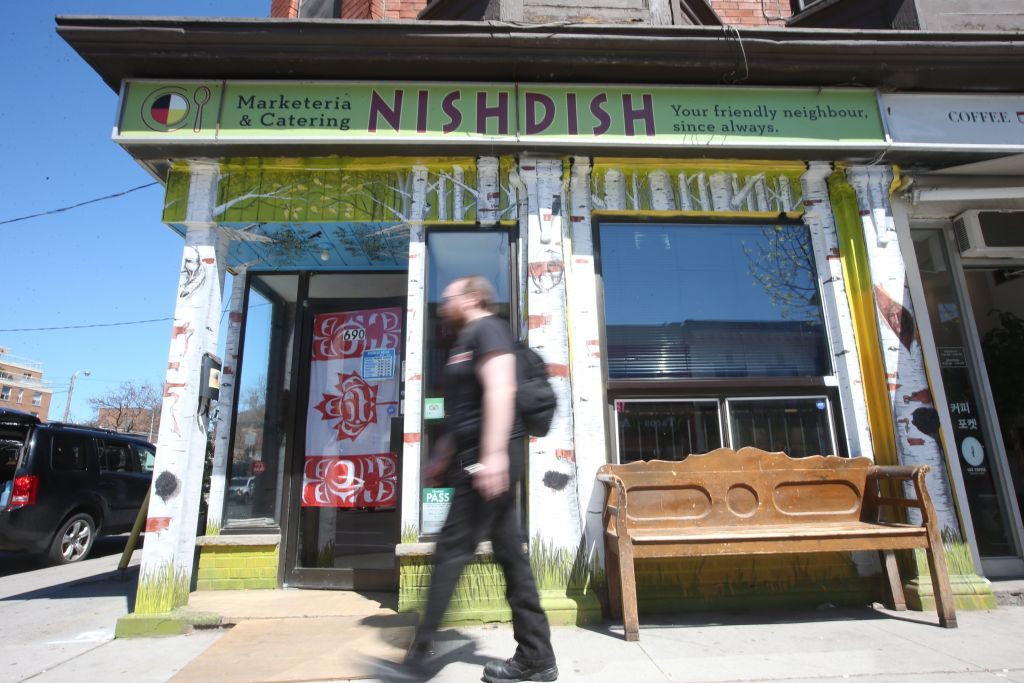

“The obstacles against indigenous people are so enormous and so embedded that we just accept that that’s how things are,” Ringuette said on a recent morning, sitting in his small Toronto restaurant, NishDish. (“Nish” is short for Anishinaabe, a group of culturally related indigenous peoples in Canada and the United States. Like many other restaurants at the moment, NishDish is now closed.)

As in the U.S., Canada put native people on reserves and sent their children to often faraway boarding schools, where their native languages and traditions were suppressed. Many suffered horrible physical and sexual abuse, under the cover of a system set up to “assimilate” them into white society. The last of these so-called residential schools closed only in the late 1990s.

These days, Canadian school children dutifully listen to a daily “acknowledgement” to the First Nations before the start of the school day. In 2015, residential schools were recognized as “cultural genocide” by a government-issued report. Yet native reserves still face high rates of drug abuse, suicide, and violence. And clashes are frequent between indigenous groups and the “settlers,” pointing to “this country’s troubled reconciliation efforts with indigenous peoples,” as a recent Toronto Star article put it. Part of what was lost during this difficult history was indigenous culinary knowledge, the focus of Ringuette’s work.

At the same time that Ringuette was carrying out his community service work, he was also seeking to learn more about his heritage. Sent to consult Mark Thompson, an Ojibwe elder and medicine man, Ringuette experienced a traditional Shake Tent ceremony for the first time.

Crucially, Thompson told Ringuette that he was a part of the Mink clan (through family affiliation, indigenous people may be associated with different animals, which symbolize different roles in the community). The mink, Ringuette explained, is “a defender of the community. In my case, they said I’m a bringer of things.” His role, he was told, was to ensure food and shelter for his community. On Thompson’s advice, Ringuette gradually moved away from jobs in social services and turned toward his “gift.” “You have the gift to bring traditional food back,” Thompson told him. “To bring the Anishinaabe diet back to the people.”

This mission would allow Ringuette to join his love of food with his commitment to social justice. A few years after the Shake Tent ceremony, in 2005, he began his successful catering business, and later—delayed by a slow rehabilitation after he was struck by a city bus in 2013—he opened the restaurant in 2017.

“Here I am bringing the food,” Ringuette said, gesturing to his restaurant. He recalled how hundreds lined up for the grand opening. “It was so beautiful … That’s how many people were excited to have some of their own traditional foods,” he said, noting that perhaps three-quarters of those customers were indigenous people.

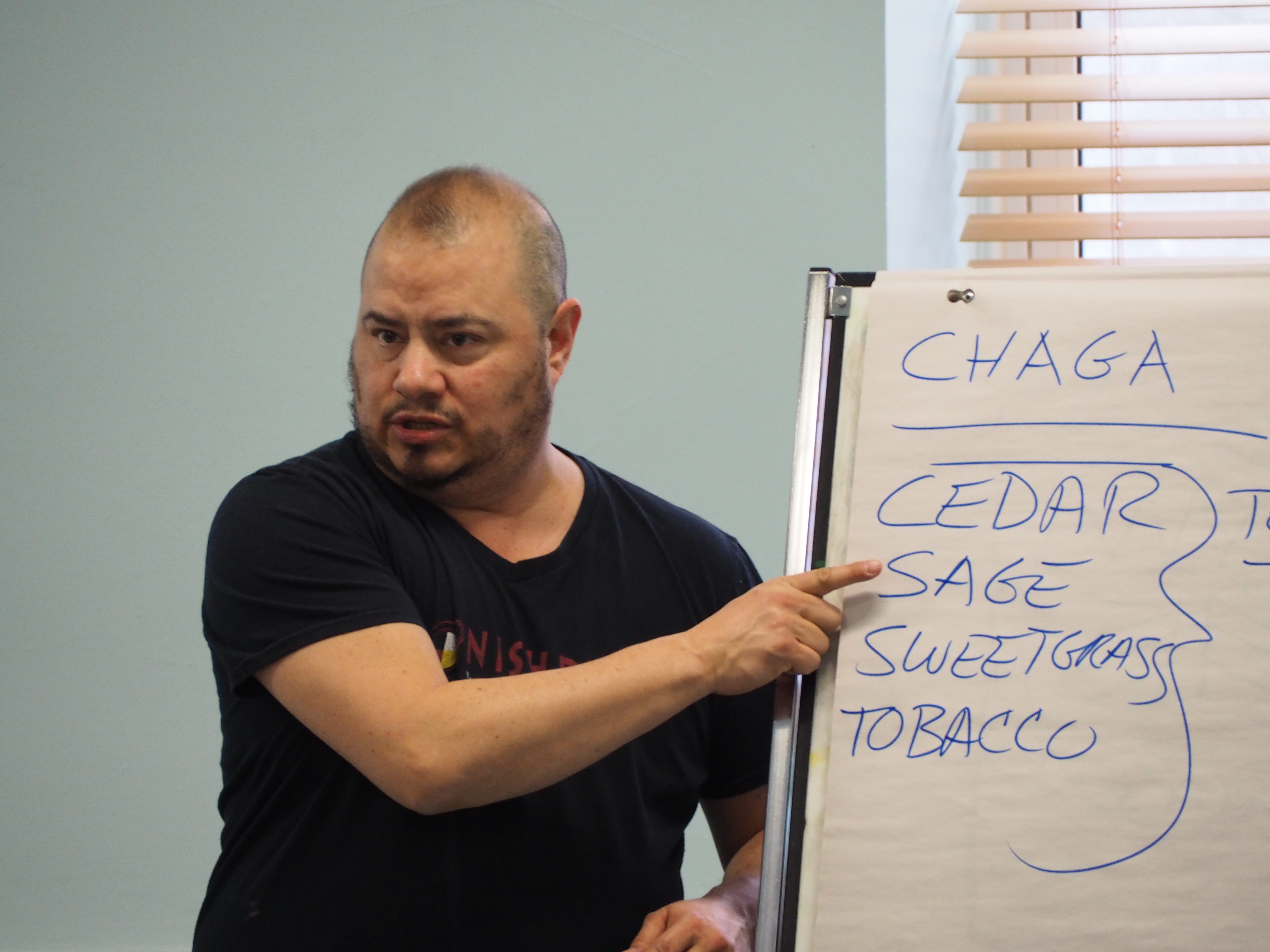

In late February, Ringuette held forth at a Toronto community health center, addressing some 25 seniors about indigenous medicinal plants and foods. Among his many projects, giving talks occupies a substantial portion of his time. To the attentive audience, he broached the central conundrum of his work.

“What is indigenous food?” he asked. “Most of our people don’t even know.” He evoked historical Canadian laws that outlawed hunting, fishing, and trapping, and that banned native languages and customs. “As a result, we don’t know what our culture is.”

As he recounted to the seniors, in the 19th century, indigenous people were often forcibly separated from traditional food sources, and non-native foodstuffs like flour, sugar, and salt were introduced in their stead. He blames these European-introduced foods for the high level of heart disease and diabetes among aboriginal people. To address such health problems, he advocates eating traditional foods. “But how do you do that when traditional foods have been eradicated?”

He regularly faces this problem in his own catering and restaurant business. According to Canadian law, it is illegal to serve wild game in a restaurant; it must be farmed. The white corn Ringuette uses in his Three Sisters Stew (the “three sisters” are corn, beans and squash) and corn soup comes from the sole commercial provider in the area, Bonnie Skye of the Six Nations of the Grand River, the largest First Nations reserve in Canada. Every six weeks, a NishDish employee has to drive the hour and a half southwest of Toronto to pick up a supply.

Toronto is traditionally a wild rice territory. But today, Ringuette has to get deliveries from Flying Wild Rice, an indigenous grower 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) northwest of Toronto. Used in both sweet and savory NishDish offerings, such as wild rice casserole, duck and wild rice soup, and wild rice-wild blueberry pudding, the rice is grown on a remote lake. When supply runs out, Ringuette admits that he has been forced to buy wild rice at the commercial chain Bulk Barn, which does not offer the same quality product. As his goal is to establish sustainable practices that give indigenous Canadians control over their own food, a chain store is clearly not his provider of choice.

To address these concerns, Ringuette founded a series of interlacing businesses and not-for-profits. In addition to NishDish, Ringuette created the Ojibiikaan Indigenous Cultural Network, a not-for-profit dedicated to indigenous food sovereignty in the Greater Toronto area. Among other initiatives, it plants indigenous gardens. Plus, through partnerships with private landowners and universities, he is researching how he might bring white corn and wild rice farming to the Toronto area. His Red Urban Nation Artist Collective has festooned a Toronto school board complex with murals, a site that hosts the occasional Indigenous Harvesters and Artisans Market, events that he hopes will become more regular.

Ringuette has targeted this complex and the public Christie Pits Park across the street as the hub of perhaps his most ambitious project, spearheaded by another one of his not-for-profit groups, the Toronto Indigenous Business Association. In an area west of Koreatown, Ringuette envisions creating what he is calling the Anishinaabe Village District, a neighborhood where indigenous people could find resources of all kinds, including businesses, libraries, and social services. Looking beyond the current coronavirus crisis, he is in talks to reopen an expanded NishDish Restaurant and Marketeria in this envisioned district. Through outreach to other local community groups, grant applications, and projects like the murals and community gardens, he is gradually making progress toward these goals.

He acknowledges, though, that fulfilling his all-encompassing mission will not be easy. As he told the seniors at the health center, he sees that establishing sovereign food lines will take generations—which only spurs him on. “Someone has to start doing something now,” he says.

Even after 15 years in the fight, he is ready to devote a lifetime to it. But he stays humble. “I’m not an elder,” he told the roomful of elderly Canadians. “I’m just a regular person learning my own culture.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook