Why a 16th-Century Artist Imagined Comets as Glorious, Fiery Swords

Explore a captivating compendium of cosmic illustrations.

Humans have long regarded comets with a swirling mix of wonder and fear: The cosmic characters figure on Babylonian tablets and a sprawling, 11th-century European tapestry. Before scientists knew exactly what caused these bright smears across the sky, comets were often interpreted as portents of doom or destruction. (Occasionally, they were blamed for less-dramatic shenanigans, such as inspiring chickens to lay oddly shaped eggs.) Given their rich history, it makes sense that an unknown artist in 16th-century Flanders compiled a lavishly illustrated compendium of comets blazing as humans cowered or gawked.

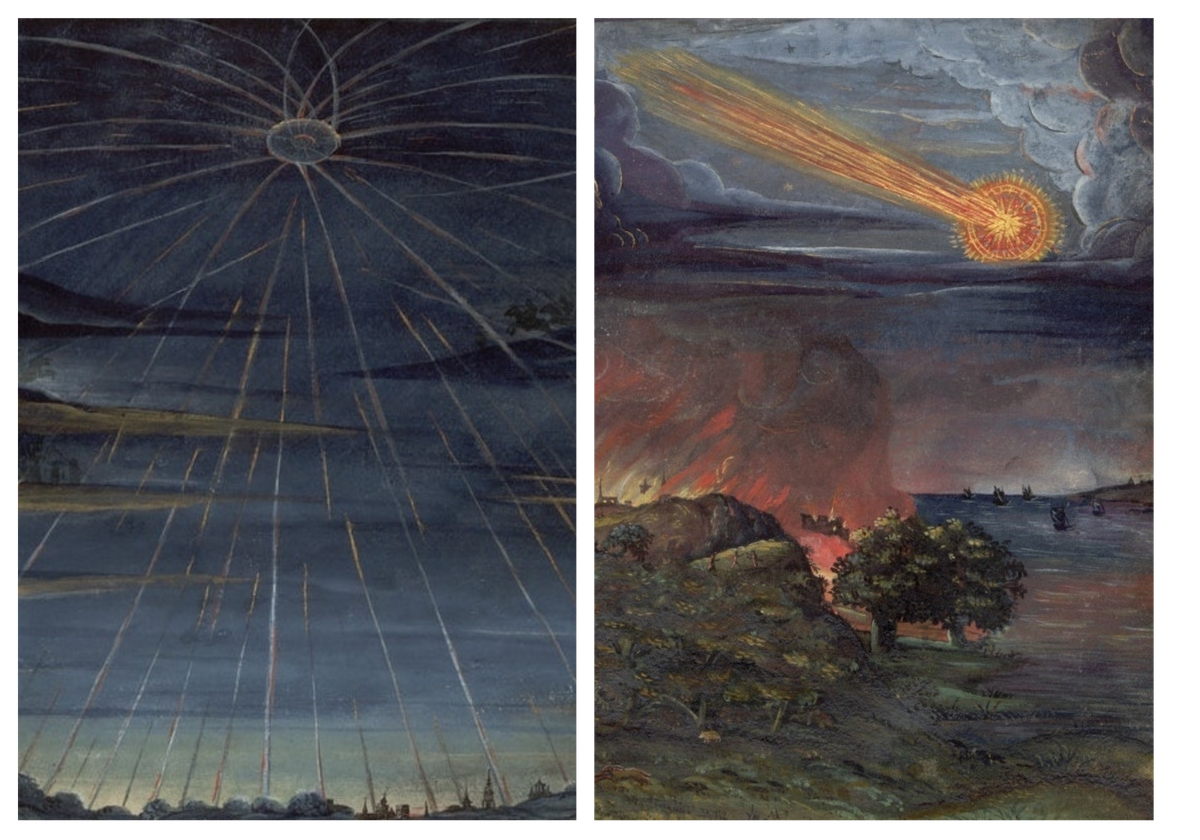

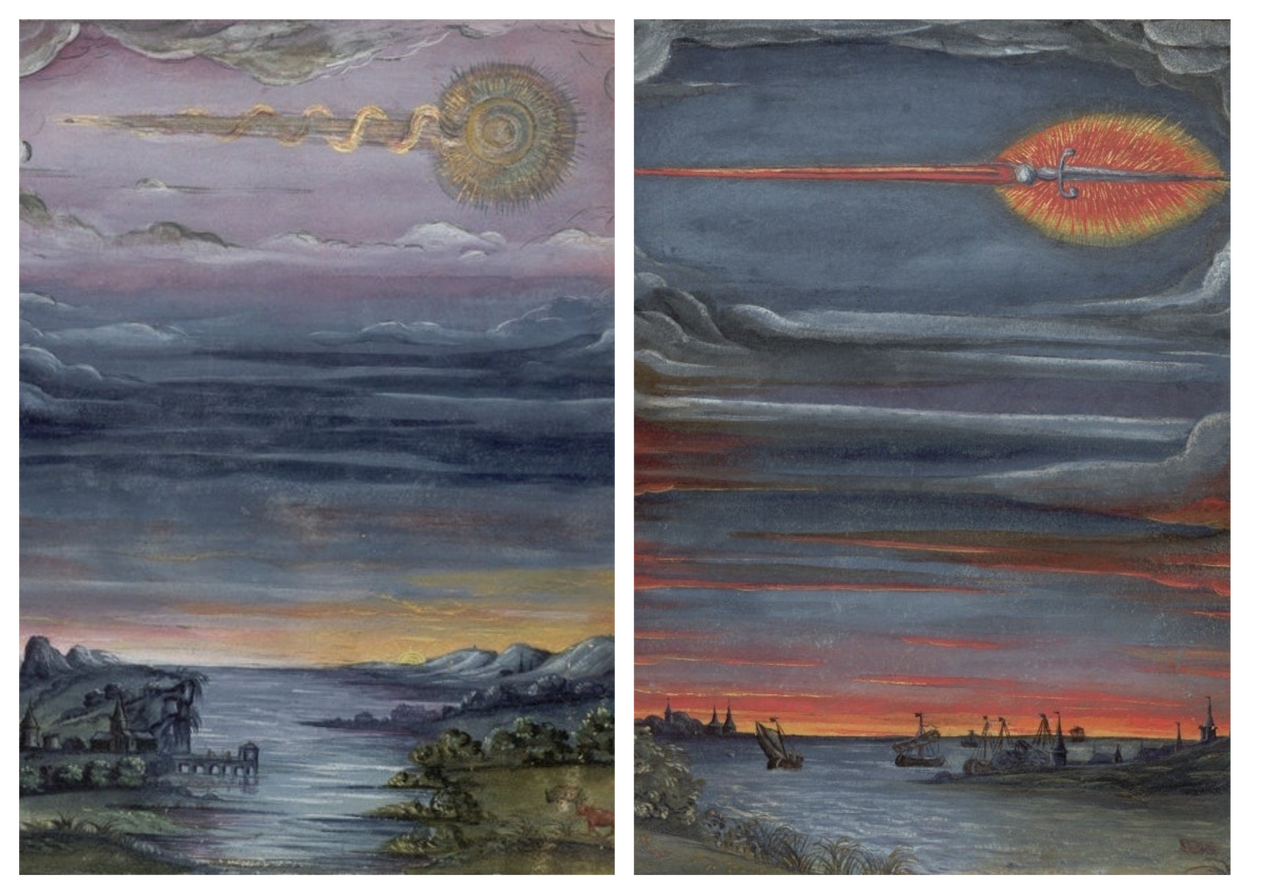

The French-language manuscript, which now resides at the Universitätsbibliothek Kassel in Germany, is colloquially known as The Comet Book. As the Public Domain Review points out, the book is preoccupied with symbolism and significance over science; its full title translates to Comets and Their General and Particular Meanings, According to Ptolemy, Albumasar, Haly, Aliquind and Other Astrologers. The Comet Book leans heavily on folklore about the objects’ supposed consequences, from fires to famines.

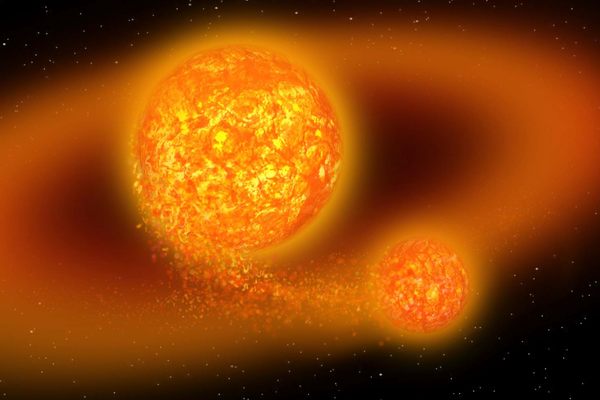

Today, we know that comets are essentially ‘dirty snowballs.’ They’re made up of frozen clumps of gas, dust, and rock that are billions of years old, remnants of the early days of our solar system. As these cold, sediment-studded masses hurtle closer to the Sun, they warm—and then fling that no-longer-so-icy material behind them in bright, smudged “tails” that can wag millions of miles across the sky.

But none of that was known when The Comet Book was created. This volume, the Public Domain Review notes, drew on an abridged, 15th-century version of a 13th-century treatise, originally written in Spain. Long before telescopes helped bring the heavens into focus, the artist of The Comet Book depicted comets in ways that emphasized the feelings of fear or awe that they stoked. One is drawn as a sharp blade; another appears to be a sun or a blisteringly hot sunflower, petals flapping cheerfully in the wind. In some images, the sky and ground are flecked with billowing flames, suggesting that the comet was seen as a harbinger of disaster.

Here, Atlas Obscura has compiled some of the remarkable images from The Comet Book. Once you’ve surveyed these historic offerings, check out some contemporary counterparts—photographs of the comet known as C/2020 F8 (SWAN)—that lit up the sky in April and May 2020.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook