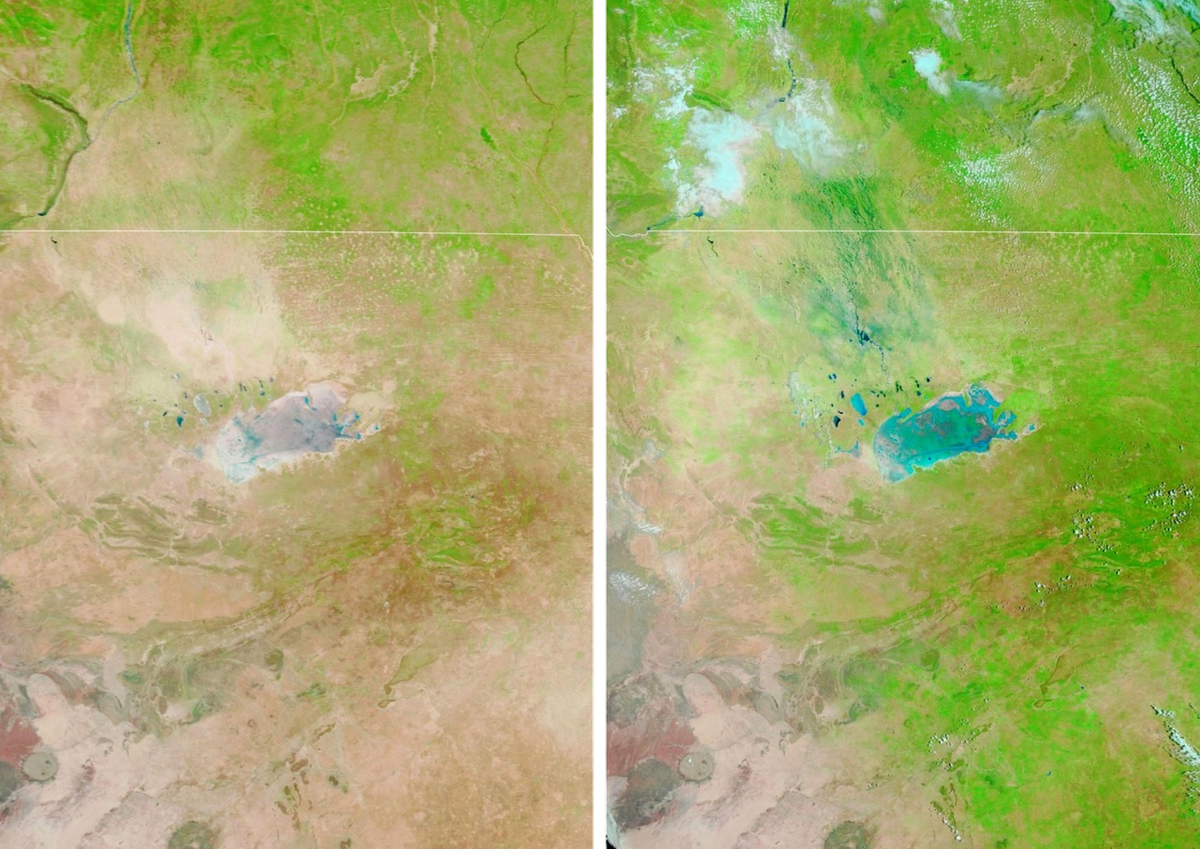

The Transformation of Namibia’s Etosha Pan, From Parched to Soaked

Satellite images track the shift from dry to wet at a vast, prehistoric lake bed in southern Africa.

The Etosha Pan, in northern Namibia, is no stranger to extremes. The white, salty landscape—leftover from a prehistoric lake that dried up millions of years ago—is often dry, cracked, and dusty; the name means the “bare place” or “the great white place” in Oshindonga, a regional dialect of the Oshiwambo language.

But when rain arrives and tops off the rivers that empty into the salt pan, it’s anything but bare: The shallow basin shimmers with highly saline water often just a few inches deep, and becomes a haven for several animal species. As new images from the NASA Earth Observatory show, that transformation from bone-dry to bluish can occur in just weeks.

On December 11, 2019, NASA’s Terra satellite pictured the Etosha Pan looking dry, and the surrounding vegetation appearing patchy. By January 17, 2020, the same area was more watery and verdant. The Namibian reports that northern Namibia was pelted with above-average rainfall in December. The rain appears to have nourished the squiggly Ekuma River, which feeds into the Etosha Pan. In the January image, the Ekuma River appears dark blue.

In the summer months when the salt pan turns watery, the 2,400-square mile landscape is a haven for animals, and tourists flock to Etosha National Park to watch them. The water is too salty for most animals to drink, according to UNESCO, but it’s a mating spot known to put white pelicans and flamingos in the mood. (Unfortunately, populations have struggled anyway.) Throughout the year, visitors might spot black rhinos, ostriches, elephants, wildebeests, zebras, and more roaming the surroundings, which include mopane woodlands, grasslands, and shrubby stretches, or congregating at spring-fed water holes that freckle the edges of the pan.

The pan is forecast to stay slick through March, NASA reported, with more downpours expected throughout the rainy season. But eventually it will be dry again, and Namibia’s hottest interspecies hang-out spot will be a little less hopping until the rains return.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook